The Colonization of Africa and the Fall of Its Kings and Kingdoms

Introduction: The Golden Age Shattered

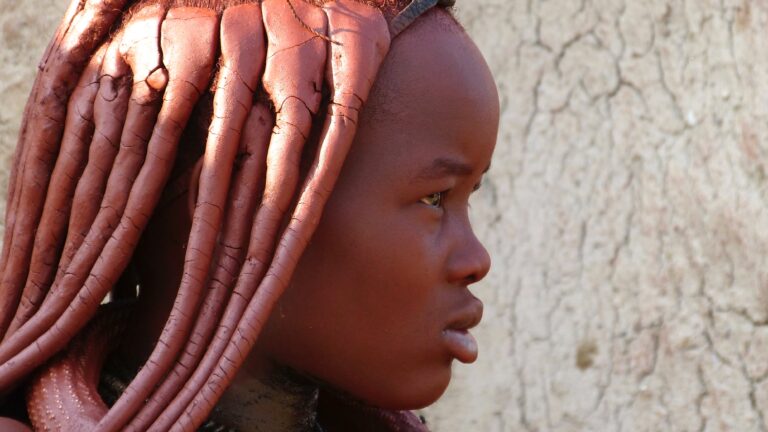

Before the white man came, Africa was a tapestry of splendor—a continent where kings ruled with wisdom, where empires stretched across savannahs and forests, and where the rhythms of life pulsed through intricate trade routes and thriving cities. From the gold-laden courts of Ashanti to the scholarly halls of the Sokoto Caliphate, from the warrior kraals of Zululand to the ancient stone churches of Ethiopia, our people built societies that rivaled any in the world. We had it good—our political systems were as sophisticated as they were diverse, blending monarchies with councils, our trade networks carried ivory, salt, and palm oil across deserts and seas, and our traditions bound us to the land and to each other in a harmony the outsiders could never fathom. This was precolonial Africa: a mosaic of kingdoms and cultures, each a jewel in its own right, gleaming under the sun of our sovereignty.

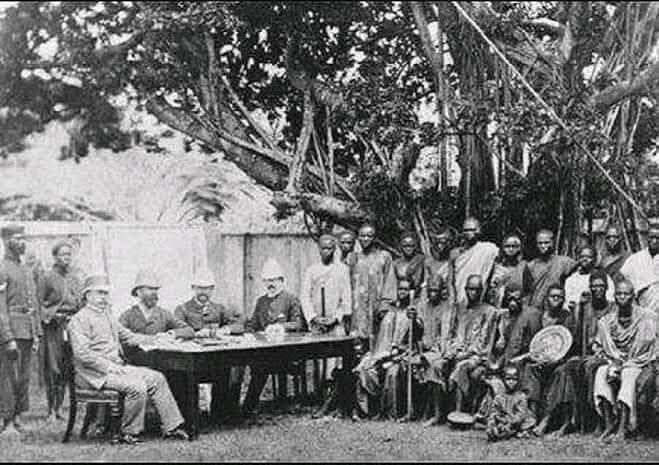

Then came the “Scramble for Africa,” a storm brewed in the late 19th century by European greed and rivalry. The white man arrived not as a guest, but as a conqueror, armed with guns we could not match, steamships that defied our rivers, and a hunger for our wealth—gold, rubber, diamonds, and the very soil beneath our feet. They called it civilization, but it was chaos cloaked in promises. Driven by economic lust and petty squabbles among their own nations, they carved up our continent like a feast at their table, ignoring the lives and legacies they trampled. The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was their banquet hall, where borders were drawn with no regard for our kings, our kin, or our histories.

Yet, our kings did not bow easily. From the defiant Kabaka Mwanga of Buganda to the cunning King Jaja of Opobo, from the fierce Omukama Kabalega of Bunyoro-Kitara to the resolute Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia, they resisted, negotiated, and fought to protect what was ours. Some wielded spears against Maxim guns, others signed treaties laced with deceit, and many fell—deposed, exiled, or erased from their thrones. This is their story: a chronicle of how our golden age was shattered, how our kingdoms were stolen, and how their struggles planted seeds of resilience that endure to this day. For every crown toppled, a legacy was forged, whispering to us across time that we once had it good—until the white man came.

West Africa: Kingdoms of Trade and Power

Before European intrusion reshaped the continent, West Africa thrived as a region of wealth and strength, where powerful kingdoms flourished amid bustling trade networks and disciplined armies. Gold, salt, and palm oil flowed through markets that rivaled any in the world, sustaining empires and city-states whose names endure in history. The arrival of colonial powers, however, brought disruption, driven by insatiable greed and a disregard for the sovereignty of these lands. This section explores the fates of several notable kingdoms:

– Kingdom of Ashanti – A gold-rich domain ruled by King Prempeh I.

– Kingdom of Dahomey – A militarized state under King Behanzin, famed for its warrior Amazons.

– Sokoto Caliphate – An expansive Islamic empire led by Sultan Ahmadu Rufai.

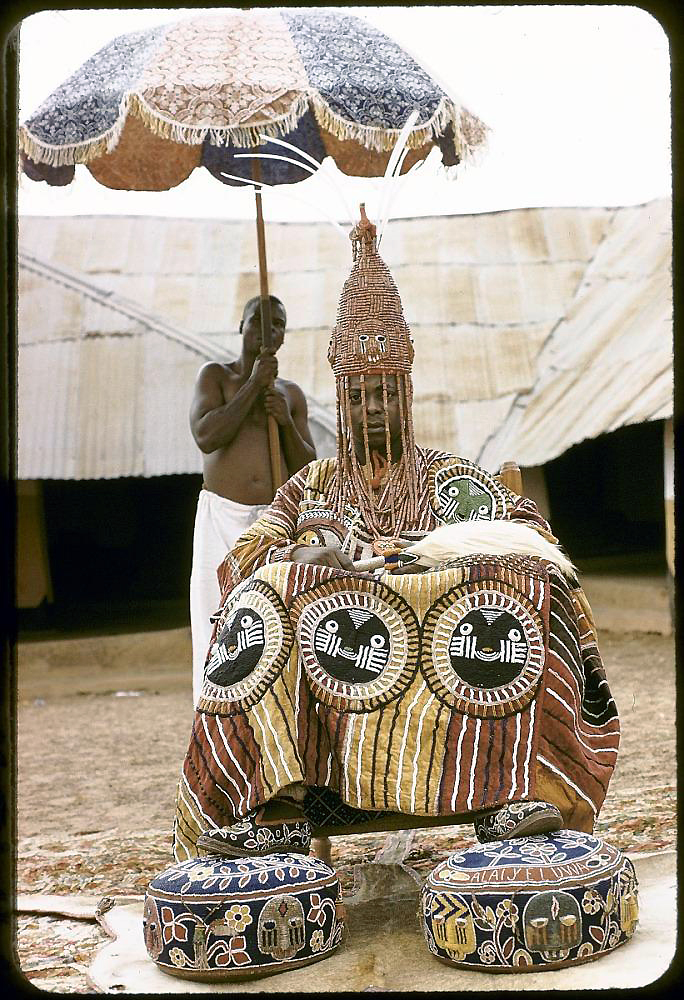

– Kingdom of Benin – A center of art and governance under Oba Ovonramwen.

– Kingdom of Opobo – A trading powerhouse established by King Jaja.

– Nembe Kingdom – A resilient delta state governed by King Frederick William Koko.

These kingdoms stood as pillars of trade and power until European ambition dismantled their foundations. The story begins with the Ashanti, whose wealth and defiance met a formidable adversary in British imperialism.

1. Kingdom of Ashanti – King Prempeh I

In the region now known as Ghana, the Kingdom of Ashanti emerged as a dominant force among the Akan people, its prosperity rooted in vast reserves of gold and a military renowned for its discipline. Prior to European interference, the Ashanti kingdom thrived under a sophisticated political system centered on the Asantehene, the supreme ruler, whose authority was symbolized by the Golden Stool—a sacred relic believed to embody the spirit of the nation. When King Prempeh I ascended the throne in 1888, he inherited a realm at its zenith. Markets in Kumasi, the royal capital, teemed with gold dust, kola nuts, and woven cloth, traded across West Africa and beyond. The kingdom’s warriors, fiercely loyal, protected a network of villages united under a single banner. Life in Ashanti was marked by order and abundance, a testament to centuries of self-governance.

The arrival of the British shattered this equilibrium. Drawn by the lure of gold and eager to expand their influence, they viewed Ashanti not as a sovereign state but as a prize to be claimed. Tensions had simmered for decades, fueled by earlier Anglo-Asante Wars where traditional weapons clashed with industrial firepower. By Prempeh I’s reign, British demands had escalated—control over trade, submission to their rule, and an end to Ashanti independence. Prempeh I resisted, seeking diplomacy over conflict. He dispatched envoys to London, hoping to preserve his kingdom’s autonomy, but such efforts fell on deaf ears, drowned out by colonial ambition.

The decisive moment came in 1896. British forces, equipped with rifles and cannons, marched on Kumasi, intent on subjugation. Prempeh I, facing overwhelming odds, chose exile over a futile bloodbath, surrendering to spare his people. The British banished him first to Sierra Leone, then to the Seychelles, stripping the Asantehene of his throne. Yet the Ashanti spirit endured. In 1900, when a British governor demanded to sit on the Golden Stool—an act of unthinkable sacrilege—the War of the Golden Stool erupted. Led by Yaa Asantewaa, the queen mother, Ashanti fighters rose in rebellion, their courage a defiant stand against domination. Though the uprising was quelled, the stool remained hidden, a symbol of resistance unclaimed by the victors.

The British formally annexed Ashanti, declaring it a colony, but they could not erase its legacy. Prempeh I returned in 1924, aged yet resolute, his presence a quiet reminder of a lost era. The Kingdom of Ashanti, once a beacon of wealth and power, fell to colonial conquest, its story a poignant chapter in the broader tale of a continent upended by European greed.

2. Kingdom of Dahomey – King Behanzin

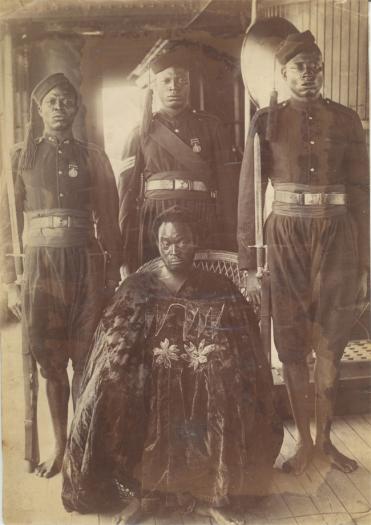

In the region now called Benin, the Kingdom of Dahomey rose as a formidable power, its name synonymous with military prowess and economic might. Before the French cast their shadow over the land, Dahomey thrived on the wealth of trade—palm oil, ivory, and, for a time, captives sold across the Atlantic. At its heart stood a disciplined army, famed for the Mino, or “Amazons,” an elite corps of female warriors whose ferocity struck fear into adversaries. Under King Behanzin, who took the throne in 1889, the kingdom reached a peak of influence. The royal city of Abomey buzzed with activity, its palaces adorned with intricate bas-reliefs recounting tales of conquest and glory. Dahomey’s rulers had long mastered the art of centralized governance, their authority unchallenged, their dominion a testament to a society that flourished in independence.

The arrival of the French disrupted this golden era. Driven by a hunger for West African resources and a desire to expand their colonial empire, they set their sights on Dahomey, viewing its trade networks as a prize to be seized. The kingdom had faced European pressure before, navigating uneasy alliances with Portuguese and British traders, but the French brought a new level of aggression. By the late 19th century, their demands grew insistent—control over ports, submission to their rule, and the dismantling of Dahomey’s sovereignty. King Behanzin, a ruler of fierce resolve, refused to yield. He rallied his forces, including the legendary Amazons, to defend the land that had prospered under his lineage for generations.

The clash came swiftly. In 1890, the First Franco-Dahomean War erupted, pitting Dahomey’s spears and muskets against French artillery and machine guns. Though the kingdom inflicted losses, the technological disparity proved stark. Undeterred, Behanzin regrouped, but the Second Franco-Dahomean War (1892–1894) sealed Dahomey’s fate. As French troops advanced on Abomey, Behanzin ordered a final act of defiance: the royal palaces, repositories of the kingdom’s history and pride, were set ablaze rather than surrendered to the invaders. The flames devoured centuries of legacy, a fiery rebuke to colonial ambition. By 1894, the French overwhelmed the defenses, capturing Behanzin and banishing him to Martinique, where he would spend his remaining years far from the throne he fought to protect.

Dahomey fell under French control, its independence extinguished, its traditions suppressed beneath the weight of colonial rule. The Amazons faded into legend, their battlefield cries silenced. Yet the memory of King Behanzin’s resistance endures, his burning of the palaces a symbol of a kingdom that refused to bow quietly. Once a powerhouse of trade and martial might, Dahomey succumbed to the relentless tide of European conquest, its story a stark reminder of a time when prosperity reigned—until the white man came.

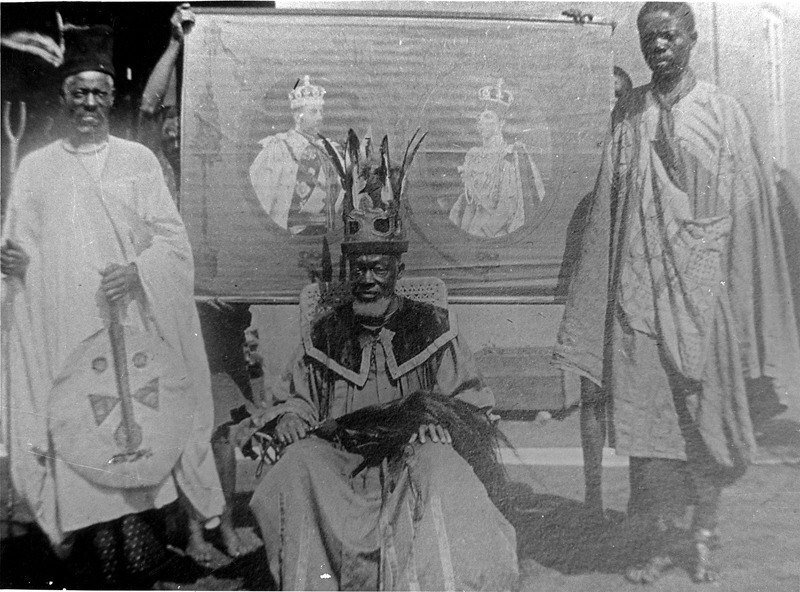

3. Sokoto Caliphate – Sultan Ahmadu Rufai

Across the expanse of what is now northern Nigeria, the Sokoto Caliphate stretched as a vast Islamic empire, its foundations laid in the early 19th century by the visionary Usman dan Fodio. Before the British encroached upon its borders, the caliphate stood as a beacon of scholarship and governance, uniting diverse peoples under the banner of faith and law. Its cities—Sokoto, Kano, Zaria—bustled with markets trading salt, leather, and textiles, while its scholars penned works of theology and poetry that rivaled the great centers of the Islamic world. By the time Sultan Ahmadu Rufai assumed leadership in the late 19th century, the caliphate governed millions, its emirs administering a network of provinces with a sophistication that bespoke centuries of cultural refinement. The land thrived in a harmony of order and devotion, its rulers revered as both spiritual and temporal guides.

The British arrival shattered this era of stability. Fueled by ambitions to dominate West Africa’s resources and trade routes, they viewed the caliphate not as a sovereign power but as an obstacle to their imperial design. The late 19th century had already brought pressures—missionaries, traders, and the creeping influence of European goods—but it was under Frederick Lugard’s command that the true threat emerged. The British sought to impose their authority, demanding submission from a realm that had known only independence. Sultan Ahmadu Rufai, inheriting a legacy of resistance from his predecessors, stood firm, unwilling to cede the caliphate’s autonomy to foreign hands.

The confrontation reached its climax in 1903. British forces, armed with Maxim guns and bolstered by colonial troops, launched a campaign to subdue the caliphate. The decisive clash came at the Battle of Burmi, where Ahmadu Rufai and his loyalists made their final stand. The caliphate’s warriors, wielding swords and muskets, faced an enemy whose technology turned bravery into sacrifice. The battle ended in defeat, the sultan’s forces overwhelmed, and Ahmadu Rufai himself fell—some accounts say in combat, others in flight. With his death, the caliphate’s heart was broken. The British declared victory, installing a system of indirect rule that preserved the emirs’ titles but stripped them of true power, reducing a once-mighty empire to a shadow under colonial oversight.

The Sokoto Caliphate, a titan of Islamic governance and learning, crumbled beneath the weight of British conquest. Its libraries grew silent, its borders redrawn to suit foreign maps. Yet the memory of its greatness persists, the Battle of Burmi a testament to a ruler and a people who defied the inevitable. Once a realm where faith and authority reigned supreme, the caliphate’s fall marked the end of an era—its prosperity and pride undone when the white man came.

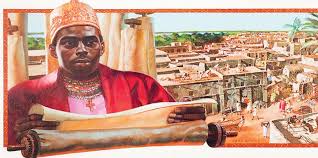

4. Kingdom of Benin – Oba Ovonramwen

In the region now known as southern Nigeria, the Kingdom of Benin thrived as a sophisticated Edo state, its legacy preserved in the exquisite bronze plaques and sculptures that graced its royal court. Before the British imposed their will, Benin stood as a testament to art, trade, and ingenuity. At its heart lay Benin City, a fortified marvel encircled by the Walls of Benin—towering earthworks stretching over 16,000 kilometers in a vast network of ramparts and moats, dwarfing even the Great Wall of China in scope. Constructed over centuries, these walls were more than defenses; they were a symbol of the kingdom’s might and permanence, shielding a bustling capital where traders exchanged ivory, pepper, and palm oil with distant lands. The guilds of Benin’s artisans crafted bronzes of unparalleled skill, while under Oba Ovonramwen, who ascended in 1888, the kingdom maintained a intricate system of governance, the Oba revered as a divine ruler. Benin flourished in a state of ordered splendor, its walls a monument to a civilization secure in its independence.

The British arrival tore this legacy asunder. Enticed by the riches of the Niger Delta and determined to dominate West African trade, they saw Benin not as a sovereign power but as a resource to plunder. European traders had long pressed for influence, their ambitions clashing with Benin’s autonomy, yet Oba Ovonramwen sought to preserve his realm’s traditions amid these encroaching threats. The breaking point came in January 1897, when a British delegation, led by Acting Consul-General James Phillips, advanced on Benin City without permission, disregarding warnings that their timing violated sacred customs. The kingdom’s warriors ambushed the party, killing most—a defensive act the British twisted into a pretext for vengeance.

The response was devastating. In February 1897, the British launched a punitive expedition, a force armed with rifles, cannons, and naval might. The Benin Massacre unfolded as the kingdom’s defenders, wielding muskets and machetes, fell before a relentless barrage. Benin City succumbed, and with it, the Walls of Benin—once an enduring emblem of strength—were breached and battered, their earthen majesty reduced to rubble in the onslaught. The city burned, its palaces and homes consumed by flames that erased centuries of history. Oba Ovonramwen, captured after months in hiding, was deposed and exiled to Calabar, his reign ended far from the throne he had fought to protect. The British looted with systematic precision, seizing thousands of bronzes including the famous mask of Queen Idia—treasures of a now-wounded culture—leaving behind a scarred landscape where the great walls once stood unbroken.

The Kingdom of Benin, a pinnacle of art and resilience, was shattered beyond recognition. Its walls, a feat of engineering that had guarded a thriving society, lay in ruins, its markets silenced, its sacred order dismantled. The burning of Benin City and the exile of Oba Ovonramwen marked the collapse of an era, the scale of destruction evident in the fallen ramparts that once defined its glory. Once a realm of beauty and power, Benin crumbled—its splendor extinguished when the white man came.

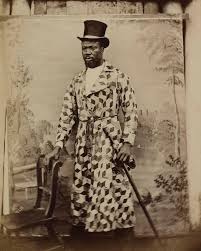

5. Kingdom of Opobo – King Jaja

In the Niger Delta, now part of Nigeria, the Kingdom of Opobo emerged as a thriving trading state, its foundations laid by an extraordinary figure: King Jaja. Born around 1821 as a slave in the Igbo hinterland, Jaja rose through sheer cunning and ambition to become a merchant prince, establishing Opobo in 1870 after breaking away from the rival Bonny state. Before British interference cast its shadow, Opobo stood as a powerhouse of commerce, its waterways alive with canoes laden with palm oil—a commodity prized across continents. Jaja’s leadership transformed the fledgling kingdom into a tightly knit polity, its markets bustling with trade that enriched both local elites and foreign partners. His palace, a wooden marvel overlooking the delta, symbolized a new era of prosperity, built on alliances with European traders yet fiercely independent. The kingdom flourished under his rule, a testament to resilience and enterprise in a region long shaped by exchange.

The British arrival upended this golden age. Drawn by the lucrative palm oil trade and intent on consolidating control over the Niger Delta, they sought to monopolize commerce, viewing Opobo’s autonomy as a threat. Jaja, a shrewd negotiator, had long balanced relations with European merchants, securing favorable terms that kept his kingdom dominant in the oil rivers. But by the 1880s, British ambitions hardened. The Royal Niger Company, backed by imperial might, pressed for exclusive rights, demanding Jaja bow to their authority and abandon his lucrative middleman role. He resisted, knowing that submission would strangle Opobo’s lifeblood. His defiance earned him enemies among the British, who masked their greed behind promises of “protection” and “free trade.”

The end came through treachery in 1887. British officials invited Jaja to a meeting aboard a warship, ostensibly to negotiate a treaty and resolve trade disputes. Assured of safe conduct, he attended, only to find himself ensnared in a calculated deception. Once aboard, he was seized, accused of obstructing commerce, and swiftly exiled—first to the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), then to St. Vincent in the Caribbean. The treaty meeting, a sham cloaked in diplomacy, stripped Opobo of its king and its independence. Without Jaja, the kingdom faltered, its trade networks co-opted by the British, its people left leaderless under colonial oversight. Jaja died in 1891 en route back to his homeland, his return permitted too late to reclaim what had been lost.

The Kingdom of Opobo, a vibrant state born of one man’s vision, withered under British domination. Its bustling waterways grew quiet, its markets subdued, its wooden palace a hollow relic of a usurped reign. The deception that removed King Jaja marked the end of an era of self-determination, a poignant reminder of a time when enterprise thrived—until the white man came with false words and iron will.

6. Nembe Kingdom – King Frederick William Koko

In the watery expanse of what is now Bayelsa, Nigeria, the Nembe Kingdom thrived as a small yet influential Ijaw state in the Niger Delta. Before British ambitions reshaped the region, Nembe held sway as a key player in the palm oil trade, its creeks and rivers humming with commerce that linked inland producers to global markets. The kingdom, though modest in size, wielded outsized authority under King Frederick William Koko, who ascended in 1889. A Christian-educated ruler with a keen grasp of trade dynamics, Koko oversaw a society adept at navigating the delta’s channels, its canoes ferrying oil barrels to European ships anchored offshore. Nembe’s strategic position and economic clout made it a vital cog in the delta’s intricate trade network, its people prospering in a rhythm dictated by tides and markets rather than foreign decrees.

The British arrival disrupted this equilibrium. Driven by a relentless pursuit of palm oil profits and control over the Niger Delta, they sought to impose their dominance, eyeing Nembe’s independence with suspicion. The Royal Niger Company, a chartered arm of British imperialism, demanded monopolistic rights over trade, pressuring local rulers to cede their autonomy. King Koko resisted, unwilling to let his kingdom become a mere conduit for British gain. He rallied Nembe’s traders and warriors, rejecting the company’s terms and maintaining direct dealings with European merchants—a defiance that challenged the colonial stranglehold on the oil rivers.

The British response was swift and brutal. On January 25, 1895, Koko launched a daring raid on the Royal Niger Company’s headquarters at Akassa, a bold strike aimed at disrupting their operations and reclaiming control. Nembe warriors attacked the outpost, destroying warehouses and seizing goods, a desperate bid to assert the kingdom’s rights. The British retaliated with overwhelming force. In February 1895, a punitive expedition—the Akassa Raid’s aftermath—descended on Nembe, armed with gunboats and artillery. The kingdom’s defenses, reliant on canoes and muskets, stood little chance against the barrage. Nembe was subdued, its trading hub crippled, and Koko forced into submission. The raid served as a grim warning to other delta states: resistance would be met with ruin.

The Nembe Kingdom, once a spirited nexus of trade and independence, faded under British hegemony. Its waterways, vibrant with commerce, grew subdued, its influence curtailed by colonial oversight. King Frederick William Koko’s stand, though crushed, lingered as a symbol of defiance, the Akassa Raid a fleeting triumph overshadowed by defeat. A small state that punched above its weight, Nembe’s fall marked the silencing of another delta voice—its prosperity dimmed when the white man came with guns and ultimatums.

East Africa: Empires of the Rift and Coast

Before European powers cast their gaze upon the region, East Africa stood as a land of empires and coastal kingdoms, where trade and tradition wove a tapestry of prosperity. From the fertile shores of the Great Lakes to the bustling ports of the Swahili coast, this region thrived on commerce in ivory, gold, and spices, its societies governed by rulers whose authority shaped the lives of millions. The arrival of colonial forces disrupted this harmony, their ambitions clashing with the sovereignty of ancient realms. This section recounts the fates of several notable kingdoms:

– Kingdom of Buganda – A centralized power under Kabaka Mwanga II.

– Bunyoro-Kitara – A rival empire ruled by Omukama Kabalega.

– Ethiopia – An ancient kingdom preserved by Emperor Menelik II.

– Zanzibar Sultanate – A coastal trade hub led by Sultan Khalid bin Barghash.

These states, each a pillar of East African heritage, faced the encroaching tide of imperialism with varying degrees of defiance and loss. The story begins with Buganda, a kingdom whose strength could not withstand the British yoke.

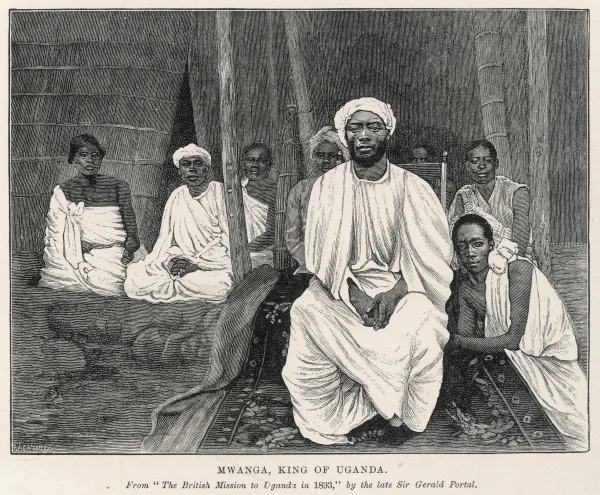

1. Kingdom of Buganda – Kabaka Mwanga II

In the heart of what is now Uganda, the Kingdom of Buganda flourished as a centralized state, its power rooted in a sophisticated blend of political organization and trade. Before British influence darkened its horizons, Buganda commanded the northern shores of Lake Victoria, its capital at Mengo a hub of activity where chiefs and clans paid tribute to the Kabaka, the supreme ruler. Under Kabaka Mwanga II, who ascended in 1884 at the age of 18, the kingdom boasted a well-structured administration, with royal officials overseeing agriculture, canoe-based trade in fish and ivory, and a military capable of enforcing order. Ganda society thrived, its people cultivating banana groves and crafting bark cloth, their lives intertwined with a monarchy that had endured for centuries. The kingdom’s influence stretched across the region, a testament to its stability and might.

The British arrival shattered this era of self-rule. Drawn by the strategic value of the Great Lakes and the promise of economic gain, they sought to bring Buganda under their dominion, their missionaries and traders paving the way for imperial control. Mwanga II inherited a realm already strained by foreign pressures—Christian and Muslim factions vied for influence, sowing discord among his court. Initially, he resisted these intrusions, executing Christian converts in 1886 to stem their growing sway, an act that earned him enmity among the British. By the 1890s, the Imperial British East Africa Company, backed by colonial ambitions, pressed for dominance, exploiting internal divisions to weaken Buganda’s resolve. Mwanga oscillated between resistance and negotiation, his youth and inexperience tested by a foe armed with both guns and guile.

The end came in stages. In 1894, Britain declared Buganda a protectorate, imposing a presence Mwanga could not expel. He rebelled in 1897, leading a revolt against the colonial forces and their local allies, but the uprising faltered against superior firepower. Defeated, he fled to German East Africa, only to be captured in 1899 and exiled to the Seychelles, his throne left vacant. The Uganda Agreement of 1900 formalized British control, granting land and privileges to collaborating chiefs while reducing the Kabaka’s role to a ceremonial figurehead. The agreement redrew Buganda’s destiny, its once-potent monarchy subordinated to colonial rule.

The Kingdom of Buganda, a bastion of order and trade, faded into the shadow of empire. Its royal court grew quiet, its autonomy stripped by foreign decrees. Kabaka Mwanga II’s exile marked the close of an independent era, the Uganda Agreement a bitter codification of loss. Once a power that shaped the region, Buganda’s fall reflected the broader fate of East Africa—its greatness dimmed when the white man came.

2. Bunyoro-Kitara – Omukama Kabalega

In the region now known as western Uganda, the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom once reigned as a dominant empire, its influence stretching across the Great Lakes before British encroachment diminished its light. Prior to colonial disruption, Bunyoro-Kitara thrived on the wealth of its cattle herds and salt deposits, resources that fueled a robust trade network with neighboring states. Its capital, Hoima, served as the seat of the Omukama, a ruler whose authority was upheld by a disciplined military and a network of chiefs. Under Omukama Kabalega, who ascended in 1870, the kingdom sought to reclaim its past glory, having rivaled Buganda in earlier centuries. Kabalega’s reign saw a resurgence of Bunyoro’s power, its pastures teeming with livestock, its salt mines bustling with activity, and its people united under a monarchy steeped in tradition. The empire stood as a pillar of prosperity and resilience, its legacy echoing through oral histories of a golden age.

The British arrival extinguished this resurgence. Drawn by the strategic importance of Uganda and eager to secure the Nile’s headwaters, they viewed Bunyoro-Kitara as an obstacle to their colonial ambitions. Kabalega, a ruler of fierce determination, faced mounting pressures as British agents and their Bugandan allies encroached on his territory. Unlike Buganda’s wavering stance, Bunyoro under Kabalega rejected compromise. He rebuilt the kingdom’s army, forging alliances with local leaders and arming his forces with muskets acquired through trade. When the British, led by figures like Frederick Lugard, sought to impose their rule in the 1890s, Kabalega met them with defiance, unwilling to let his empire bow to foreign domination.

The struggle unfolded over years of relentless conflict. From 1894 to 1899, Kabalega waged a guerrilla war against British forces, a campaign of ambushes and raids that exploited Bunyoro’s rugged terrain. His warriors struck at colonial outposts, disrupting supply lines and challenging the invaders’ advance. The British, armed with Maxim guns and reinforced by Bugandan troops, responded with overwhelming force, burning villages and seizing cattle to break Bunyoro’s resistance. Despite early successes, Kabalega’s campaign could not withstand the technological disparity. In 1899, he was captured alongside Kabaka Mwanga II of Buganda, his ally in exile, after a betrayal by local collaborators. The British banished him to the Seychelles, where he remained until 1923, returning only to die shortly after.

The Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, once a rival to empires and rich in resources, crumbled under British conquest. Its pastures fell silent, its salt trade redirected to colonial coffers, its royal lineage reduced to a memory. Omukama Kabalega’s guerrilla resistance stood as a testament to Bunyoro’s unyielding spirit, a desperate bid to preserve an empire that had flourished for centuries. Yet the British triumph marked the end of its independence, a stark reminder of a time when cattle roamed free and salt sustained a proud people—until the white man came with fire and chains.

3. Ethiopia – Emperor Menelik II

In the rugged highlands of the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia stood as an ancient Christian empire, its roots tracing back millennia before European powers sought to claim the continent. Long before Italian ambitions threatened its borders, Ethiopia thrived as a bastion of independence, its emperors reigning from stone palaces and rock-hewn churches carved into the earth. The kingdom’s wealth flowed from agriculture—teff, coffee, and cattle sustained a robust economy—while its trade routes linked the interior to Red Sea ports, exchanging gold and ivory with distant lands. Under Emperor Menelik II, who ascended in 1889, Ethiopia entered a period of consolidation and modernization. Menelik unified fractious provinces, armed his forces with imported rifles, and established Addis Ababa as a new capital, its markets alive with the hum of a self-sufficient realm. Rooted in a Christian tradition that predated Europe’s, Ethiopia stood apart, its sovereignty unbroken by foreign hands.

The Italian arrival tested this enduring independence. Driven by colonial fervor and a desire to carve an empire in East Africa, Italy eyed Ethiopia as a prize, its leaders dismissing the kingdom as a primitive land ripe for conquest. The Italians had already seized Eritrea along the coast, using it as a foothold to press inward. Menelik II, a shrewd and resolute ruler, recognized the threat. He negotiated with European powers to secure weapons, amassing an arsenal to match the invaders’ technology, while rallying his people—nobles, warriors, and peasants alike—under a banner of national pride. When Italy, emboldened by treaties Menelik contested, marched into Ethiopian territory in 1895, the stage was set for a confrontation unlike any other in the Scramble for Africa.

The clash culminated on March 1, 1896, at the Battle of Adwa. Menelik II led an army of over 100,000, a coalition of regional forces armed with rifles and spears, against an Italian contingent bolstered by colonial troops. The Italians underestimated their foe, their lines faltering under the weight of Ethiopia’s disciplined assault. By day’s end, the invaders lay defeated, their ambitions crushed on the rocky slopes of Adwa. The victory stunned Europe, securing Ethiopia’s independence and forcing Italy to retreat. Menelik’s triumph at Adwa stood as a rare success story, a beacon of resistance in a continent overrun by colonial powers. Though later years brought renewed pressures, his reign preserved Ethiopia’s ancient legacy.

Ethiopia, a kingdom of faith and resilience, defied the tide that submerged its neighbors. Its fields remained its own, its churches untouched by foreign rule. Emperor Menelik II’s victory at Adwa marked a singular chapter, proving that the white man’s advance could be halted—its greatness enduring where others fell. Yet even this triumph could not shield Ethiopia forever, a reminder of a time when independence reigned supreme, briefly unbroken by the shadow of conquest.

4. Zanzibar Sultanate – Sultan Khalid bin Barghash

Off the coast of what is now Tanzania, the Zanzibar Sultanate thrived as a Swahili trade hub under Omani rule, its island shores a crossroads of commerce before British dominance swept it away. Prior to colonial interference, Zanzibar flourished as a jewel of the Indian Ocean, its stone town bustling with merchants trading cloves, ivory, and spices across continents. The sultanate, established by Omani Arabs in the 19th century, grew rich on the clove plantations that perfumed the air, its dhows slicing through turquoise waters to connect Africa, Arabia, and India. Under Sultan Khalid bin Barghash, who seized power in August 1896, Zanzibar stood as a vibrant maritime state, its palaces of coral stone reflecting a blend of Arab, Swahili, and Indian influences. The sultanate’s wealth and strategic position made it a beacon of prosperity, its rulers wielding authority over a cosmopolitan realm unbound by European chains.

The British arrival extinguished this golden era. Driven by imperial rivalry and a desire to control East African trade routes, they had long exerted influence over Zanzibar, installing puppet sultans to secure their interests. When Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, a British-backed ruler, died suddenly on August 25, 1896, Khalid bin Barghash saw an opportunity. Defying British wishes, he declared himself sultan, rallying loyalists to the palace in a bid to assert independence. The British, unwilling to tolerate a ruler they could not manipulate, issued an ultimatum: surrender by 9:00 a.m. on August 27 or face bombardment. Khalid refused, barricading himself with a small force, his defiance a fleeting challenge to the colonial grip tightening around the sultanate.

The response was swift and merciless. At 9:02 a.m. on August 27, 1896, British warships opened fire on Zanzibar’s waterfront, unleashing a barrage of shells in what became the Anglo-Zanzibar War—the shortest conflict in history, lasting 38 minutes. The sultan’s palace crumbled under the onslaught, its wooden roofs ablaze, while his makeshift navy—a single yacht—was sunk in the harbor. Outmatched by gunboats and artillery, Khalid fled to the German consulate, leaving his kingdom in ruins. By 9:40 a.m., the British had deposed him, installing a compliant successor and declaring Zanzibar a protectorate. The 38-minute war crushed the sultanate’s bid for sovereignty, its brevity a stark measure of colonial might over a once-proud state.

The Zanzibar Sultanate, a thriving nexus of trade and culture, fell silent under British rule. Its clove-scented breezes carried the echo of loss, its stone town subdued by foreign decrees. Sultan Khalid bin Barghash’s brief reign ended in exile, the Anglo-Zanzibar War a fleeting yet bitter testament to resistance overwhelmed. Once a maritime power that bridged worlds, Zanzibar’s independence vanished—its splendor faded when the white man came with cannon and clockwork precision.

Central Africa: Realms of the Interior

Deep within the heart of the continent, Central Africa thrived as a region of ancient kingdoms and resource-rich lands before European greed carved it apart. Its dense forests, winding rivers, and fertile plains sustained societies that mastered trade and governance, their rulers commanding respect across vast territories. Copper, salt, and ivory flowed through these realms, linking them to distant markets long before colonial flags rose. The arrival of European powers shattered this independence, their ambitions slicing through the interior with little regard for its heritage. This section explores the fates of key states:

– Kongo Kingdom – A Christian realm shaped by King Afonso I and his successors.

– Lunda Empire – A trade-based empire under the Mwata Yamvo rulers.

These kingdoms, once masters of their domains, faced the relentless tide of imperialism, their stories a testament to a lost era. The narrative begins with the Kongo Kingdom, a power undone by early ties that turned to chains.

1. Kongo Kingdom – King Afonso I (and Successors)

Spanning what is now Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Republic of Congo, the Kongo Kingdom emerged as a formidable state, its roots stretching back to the 14th century before European intrusion unraveled its fabric. Prior to Portuguese contact, Kongo thrived as a centralized realm, its capital at Mbanza Kongo a bustling center of trade and culture. The kingdom’s wealth came from copper, raffia cloth, and ivory, exchanged along the Congo River and beyond. When King Afonso I ascended in 1509, he embraced Christianity following early encounters with Portuguese explorers, forging a partnership that elevated Kongo’s status. Under his reign, the kingdom adopted European literacy and faith, blending them with local traditions to create a vibrant Christian state. Afonso’s court boasted schools and churches, his authority upheld by a network of nobles and a military clad in woven armor. Kongo stood as a beacon of sophistication, its prosperity a reflection of a society in command of its destiny.

The Portuguese presence, initially a source of alliance, soon morphed into a harbinger of ruin. What began as trade—guns, cloth, and ideas—shifted to exploitation as Portugal’s appetite grew. Afonso I sought to control this relationship, welcoming missionaries while resisting the slave trade that began to drain his kingdom. His letters to Lisbon, pleading for restraint, went unheeded as Portuguese traders and their local allies escalated abductions, shipping Kongolese across the Atlantic. After Afonso’s death in 1543, his successors faced mounting pressures, their power eroded by the very ties he had nurtured. By the 19th century, the kingdom weakened, fractured by internal strife and the relentless slave trade that Portugal fueled for centuries.

The final blow came in the 1880s, when European powers partitioned Central Africa. The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 formalized this dismemberment, with Belgium claiming the Congo Free State and Portugal seizing Angola, splitting Kongo’s heartland between them. No Kongolese ruler sat at that table in Berlin, where lines were drawn with ink and avarice, ignoring the kingdom’s ancient boundaries. The last kings, reduced to figureheads, watched as their lands were swallowed—forests felled, rivers redirected, people subjugated. The conference cemented Kongo’s fall, its sovereignty erased by colonial decrees that cared nothing for its past.

The Kongo Kingdom, once a Christian power of trade and resilience, faded into fragments under European rule. Its capital crumbled, its copper and cloth supplanted by rubber and exploitation. King Afonso I’s vision of a thriving realm, sustained by his successors, dissolved in the wake of the Berlin Conference, a stark marker of loss. A kingdom that had blended worlds succumbed—its greatness undone when the white man came with promises turned to plunder.

2. Lunda Empire – Mwata Yamvo Rulers

Across the savannahs and forests of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, and Zambia, the Lunda Empire flourished as a trade-based realm, its influence woven through a decentralized network of chieftains before European powers unraveled its threads. Established in the 16th century, the empire thrived under the Mwata Yamvo, a title held by successive rulers who commanded loyalty from afar. Prior to colonial encroachment, Lunda’s wealth flowed from copper, salt, and ivory, traded across Central Africa and beyond through a web of tributaries and allies. Villages dotted the landscape, their chiefs paying homage to the Mwata Yamvo in a system that balanced local autonomy with imperial oversight. The empire’s markets bustled with goods, its people skilled in metallurgy and agriculture, their lives sustained by a realm that stretched over vast distances. Lunda stood as a testament to adaptability and enterprise, its decentralized rule a strength that bound diverse peoples in prosperity.

The arrival of Belgian and Portuguese forces dismantled this intricate order. Drawn by the region’s mineral riches and strategic position, they crept into Lunda’s territory in the late 19th century, their ambitions fueled by the Scramble for Africa. The empire had encountered outsiders before—Arab and Swahili traders had long bartered along its edges—but European colonial powers brought a new menace. Missionaries and explorers paved the way, their presence softening the ground for conquest. The Mwata Yamvo rulers, presiding over a loose confederation, faced a challenge unlike any other: invaders armed with guns and intent on domination. Initial encounters were subtle—trade deals and treaties laced with promises—yet these soon gave way to coercion as Belgium and Portugal sought to carve up the empire between them.

The subjugation unfolded gradually, lacking the drama of a single battle yet no less devastating. By the late 19th century, Belgian forces from the Congo Free State and Portuguese troops from Angola began co-opting Lunda’s rulers, exploiting the empire’s decentralized nature. Chiefs were bribed or pressured into submission, their allegiance shifted from the Mwata Yamvo to colonial administrators. The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 had already set the stage, drawing borders that sliced through Lunda’s heartland, but it was this slow erosion of authority that sealed its fate. The Mwata Yamvo, once a revered sovereign, became a figurehead under foreign oversight, his power diminished as tribute turned to taxes and trade routes fell to European control. Resistance flickered—some chiefs defied the intruders—but the empire’s structure, built for flexibility, could not withstand the systematic dismantling.

The Lunda Empire, a sprawling realm of trade and tradition, faded into the shadows of colonial rule. Its copper mines fed foreign coffers, its markets subdued by new masters. The gradual co-option of its rulers marked the end of an era, the Mwata Yamvo’s influence reduced to a hollow echo of its past. Once a power that bridged nations, Lunda succumbed—its greatness undone when the white man came with quiet force and relentless greed.

Southern Africa: Warriors and Cattle Kings

In the rolling hills and grasslands of Southern Africa, kingdoms rose as bastions of martial prowess and pastoral wealth before European settlers and soldiers cast their shadow over the land. This region thrived on cattle, a currency of power and sustenance, its societies governed by rulers whose warriors defended sprawling territories. From the cattle kraals of the interior to the mineral-rich frontiers, Southern Africa pulsed with life and independence, its people skilled in war and husbandry. The arrival of colonial powers shattered this sovereignty, their greed for land and resources clashing with the might of warrior kings. This section recounts the fates of two notable states:

– Zulu Kingdom – A militarized realm under King Cetshwayo.

– Ndebele Kingdom – A warrior state ruled by King Lobengula.

These kingdoms, forged in strength and tradition, faced the relentless advance of imperialism, their stories a testament to a lost age of warriors and cattle kings. The narrative begins with the Zulu Kingdom, a power undone by British ambition.

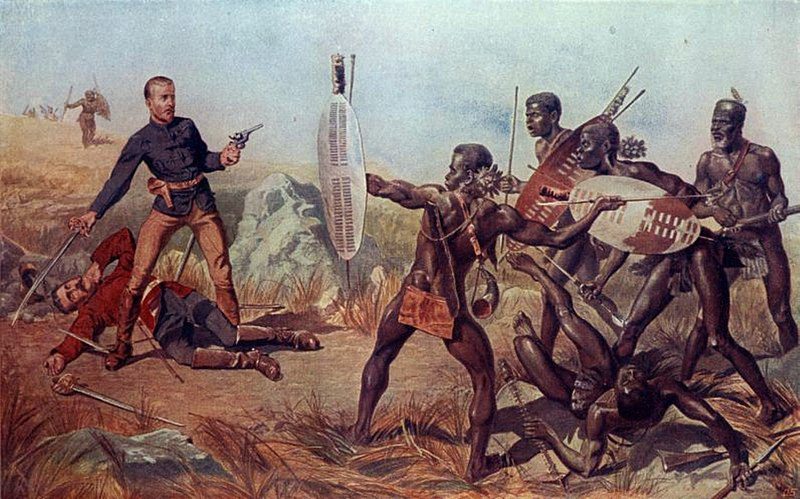

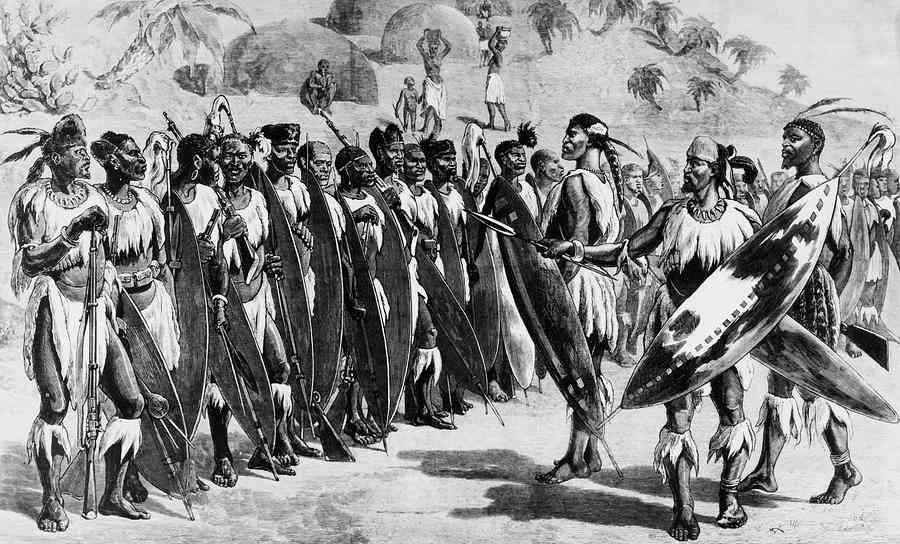

1. Zulu Kingdom – King Cetshwayo

In the region now known as South Africa, the Zulu Kingdom stood as a militarized state, its name synonymous with discipline and defiance before British forces brought it to its knees. Founded in the early 19th century under Shaka Zulu, the kingdom had transformed from a small chiefdom into a formidable empire, its strength rooted in a revolutionary military system. By the time King Cetshwayo ascended in 1873, the Zulus commanded a vast territory in what is now KwaZulu-Natal, their kraals teeming with cattle—the lifeblood of their economy and a symbol of wealth. The Zulu army, trained in Shaka’s disciplined formations, wielded assegais and shields with precision, their regiments—or *impis*—capable of swift, devastating assaults. Villages thrived under a centralized monarchy, their fields yielding maize and millet, their society bound by rituals and loyalty to the king. The Zulu Kingdom flourished as a beacon of martial might and pastoral prosperity, its independence unchallenged by distant powers.

The British arrival shattered this era of dominance. Drawn by the strategic need to secure Southern Africa and spurred by settlers’ demands for land, they viewed the Zulu Kingdom as a threat to their expanding Cape Colony. Cetshwayo inherited a realm already under pressure—Boer farmers encroached from the west, and British officials eyed the fertile plains with growing intent. In 1878, tensions boiled over when Britain issued an ultimatum, demanding Cetshwayo disband his army and submit to colonial authority—an edict designed to provoke rather than negotiate. The king refused, his pride and the Zulu legacy of resistance leaving no room for surrender. The stage was set for a confrontation that would echo across the continent.

The clash erupted in January 1879 with the Battle of Isandlwana, a stunning Zulu triumph. On January 22, Cetshwayo’s *impis*, numbering over 20,000, descended on a British encampment, their crescent-shaped formation overwhelming an overconfident foe. Armed with spears and a handful of muskets, the Zulus annihilated a force equipped with rifles and artillery, killing over 1,300 soldiers in a rout that shocked the empire. Isandlwana stood as a testament to Zulu prowess, a fleeting victory that proved African kingdoms could humble European might. Yet the British response was unrelenting. Reinforced and vengeful, they launched a counteroffensive, culminating in the Battle of Ulundi on July 4, 1879. Artillery and Gatling guns tore through Zulu lines, burning the royal kraal and breaking the kingdom’s spine. Cetshwayo fled, only to be captured in August and exiled to Cape Town, his reign ended far from the land he had defended.

The Zulu Kingdom, a titan of warriors and cattle, fell under British dominion. Its kraals were seized, its army disbanded, its territory carved into fragments by colonial administrators. King Cetshwayo’s exile marked the close of an independent era, the Battle of Isandlwana a glorious but fleeting stand against an implacable foe. Once a realm where cattle lowed and warriors danced, the Zulu Kingdom succumbed—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with steel and fire.

2. Ndebele Kingdom – King Lobengula

In the region now known as Zimbabwe, the Ndebele Kingdom rose as a warrior state, its roots entwined with Zulu traditions before British treachery and force brought it low. Founded in the early 19th century by Mzilikazi, a Zulu general who fled north after clashing with Shaka, the Ndebele carved out a powerful domain in the Matabeleland plateau. By the time King Lobengula ascended in 1868, the kingdom thrived as a cattle-rich society, its herds grazing across vast grasslands, a source of wealth and prestige. The Ndebele army, modeled on Zulu impis, wielded spears and shields with disciplined ferocity, their raids ensuring dominance over neighboring peoples. Bulawayo, the royal capital, buzzed with activity—kraals housed livestock, smiths forged weapons, and tribute flowed from vassal tribes. The kingdom stood as a testament to martial prowess and pastoral abundance, its independence a legacy of resilience in a turbulent region.

The British arrival unraveled this proud realm. Drawn by rumors of gold and driven by Cecil Rhodes’ vision of a Cape-to-Cairo empire, they saw the Ndebele Kingdom as both a prize and a barrier. Lobengula faced mounting pressures—Boer settlers probed from the south, and British prospectors circled like vultures, their eyes fixed on the mineral wealth beneath Matabeleland. A shrewd ruler, he sought to navigate these threats, granting limited concessions to keep foreigners at bay. In 1888, this caution faltered with the Rudd Concession, a deceptive pact orchestrated by Rhodes’ envoy, Charles Rudd. Presented as a simple mining agreement, the document—signed under duress and misrepresentation—granted the British South Africa Company sweeping rights to land and resources. Lobengula, misled about its scope, later repudiated it, but the damage was done: Britain claimed it as a legal foothold.

The betrayal ignited conflict. In 1893, tensions over land and cattle theft—some provoked by British settlers—erupted into war. The British South Africa Company, armed with Maxim guns and artillery, marched on Bulawayo, clashing with Ndebele warriors in a series of battles from 1893 to 1894. Despite fierce resistance, the Ndebele could not match the invaders’ firepower. Bulawayo fell, its royal kraal torched, and Lobengula fled north with his loyalists. His fate remains shrouded—some say he died of illness, others of wounds, his end lost to history amid the chaos of defeat. By 1894, the British had crushed the kingdom, establishing Rhodesia over its ashes, the Ndebele subdued under colonial rule.

The Ndebele Kingdom, a warrior state of cattle and courage, vanished beneath British dominion. Its herds were plundered, its warriors scattered, its capital reduced to a memory. King Lobengula’s undoing, sparked by the Rudd Concession deception, marked the end of an era, a bitter lesson in trust betrayed. Once a power that echoed Zulu might, the Ndebele fell—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with lies and lead.

North Africa: The Maghreb and Beyond

Across the sun-scorched sands and fertile coasts of North Africa, kingdoms and states flourished as centers of culture and power before European domination reshaped their destinies. This region, stretching from the Atlantic to the Nile, thrived on trade in gold, salt, and grain, its cities gleaming with mosques and markets that linked Africa to the Mediterranean world. Ruled by dynasties and tribal leaders, North Africa blended Islamic traditions with ancient legacies, its people adept at navigating desert and sea. The arrival of colonial powers disrupted this rich heritage, their economic and military might overwhelming states that had long stood independent. This section explores the fates of key realms:

– Egypt – A modernizing Ottoman vassal under Khedive Ismail and his successors.

– Algeria – A tribal confederation led by Emir Abdelkader.

– Morocco – A Sharifian dynasty ruled by Sultan Moulay Hassan I.

These lands, once masters of their fates, faced the encroaching tide of imperialism, their stories a testament to a vanished era. The narrative begins with Egypt, a kingdom whose ambitions could not withstand British chains.

1. Egypt – Khedive Ismail (and Successors)

In the fertile valley of the Nile, now modern Egypt, a semi-autonomous state thrived under Ottoman suzerainty, its aspirations soaring before British occupation clipped its wings. Long before European control, Egypt stood as a cradle of civilization, its fields watered by the river that sustained a bustling economy of cotton, grain, and trade. Under Khedive Ismail, who ruled from 1863 to 1879, the country embarked on a rapid modernization drive. Ismail, granted the title of Khedive by the Ottoman Sultan, envisioned a European-style Egypt—railways stretched across the land, the Suez Canal opened in 1869, and Cairo transformed with grand boulevards and opera houses. The nation’s ports hummed with commerce, its cotton exports fueling a treasury that, for a time, rivaled those of smaller European states. Egypt prospered as a modernizing power, its rulers balancing Ottoman oversight with a bold push for independence and prestige.

The British arrival turned this dream to dust. Enticed by the Suez Canal’s strategic value and Egypt’s economic potential, they watched as Ismail’s ambitions led to financial ruin. His lavish projects, funded by European loans, plunged Egypt into debt, a vulnerability Britain exploited. By 1879, mounting pressure from creditors—chiefly British and French—forced Ismail’s deposition, replaced by his son Tawfiq under foreign supervision. Egyptian discontent simmered, erupting in 1881 under Colonel Ahmed Urabi, who rallied against European influence and a weakened Khedive. Britain, fearing loss of control over the canal, intervened decisively. On September 13, 1882, the Battle of Tel El Kebir saw British forces, armed with rifles and artillery, crush Urabi’s army in a dawn assault, their victory swift and absolute. Egypt fell under occupation, Tawfiq retained as a powerless figurehead, his authority a hollow shell beneath British rule.

The occupation entrenched foreign dominance. Britain declared Egypt a protectorate in 1914, but the seeds were sown at Tel El Kebir—its economy redirected to serve imperial needs, its canal a lifeline for British ships. Successive Khedives, from Tawfiq to Abbas Hilmi II, reigned as puppets, their palaces overshadowed by colonial administrators. Egypt, once a beacon of progress and pride, lost its sovereignty, its fields and waterways harnessed for another’s gain. The Battle of Tel El Kebir marked the end of an era of self-determination, a stark reminder of a time when modernization promised greatness—until the white man came with debts and bayonets.

2. Algeria – Emir Abdelkader

In the rugged expanse of what is now Algeria, a land of mountains, deserts, and fertile plains thrived under tribal governance before French conquest tore it asunder. Prior to European domination, this region flourished as a mosaic of Berber and Arab tribes, its people herding livestock, cultivating olives, and trading across the Maghreb. Though nominally under Ottoman rule, local leaders held sway, their autonomy rooted in centuries of tradition. When France invaded in 1830, seizing Algiers and sparking unrest, Emir Abdelkader emerged as a unifying figure. Born in 1808 to a scholarly family, Abdelkader rose in 1832 as a resistance leader, rallying tribes under a banner of faith and defiance. His leadership forged a proto-state, its markets bustling with goods, its warriors armed with muskets and resolve. This nascent realm stood as a bulwark of independence, its people united in a way unseen before, their lives enriched by a shared purpose against a foreign foe.

The French arrival shattered this fragile unity. Driven by a desire to expand their empire and secure North African resources, they launched a relentless campaign, their armies equipped with rifles and artillery. Abdelkader, a skilled tactician and devout Muslim, countered with guerrilla tactics, striking French outposts and supply lines across the Atlas Mountains. By 1834, he had established a resistance state, complete with a capital at Mascara, a treasury, and a network of tribal allies. This state imposed order—taxes funded defenses, Islamic law guided governance, and trade sustained its people. For over a decade, Abdelkader’s forces held the French at bay, their victories a testament to a leader who turned scattered tribes into a formidable power. Treaties like the 1837 Tafna accord briefly paused the conflict, granting him control over much of the interior, but France’s hunger for total dominion proved insatiable.

The end came in 1847, worn down by relentless pressure. French General Thomas Bugeaud escalated the war, burning villages and employing scorched-earth tactics to break Abdelkader’s support. Outnumbered and outgunned, his resistance state crumbled as tribes surrendered or fled. In December 1847, Abdelkader surrendered under a promise of safe passage to the Middle East, only to be betrayed—France exiled him to France instead, imprisoning him until 1852, then releasing him to Damascus, where he died in 1883. Algeria fell fully under French rule, its lands declared a colony, its people subjected to settlers and suppression. The formation of Abdelkader’s resistance state, a fleeting beacon of unity, faded into memory, its promise drowned by colonial might.

Algeria, once a land of free tribes and thriving trade, succumbed to French domination. Its plains were parceled out to settlers, its traditions buried beneath foreign laws. Emir Abdelkader’s resistance state stood as a defiant chapter, a rare fusion of strength and vision undone by betrayal. A realm that briefly shone with independence vanished—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with fire and false promises.

3. Morocco – Sultan Moulay Hassan I

In the land now known as Morocco, a Sharifian dynasty reigned over a kingdom of rugged mountains, fertile valleys, and bustling ports before European powers imposed their will. Prior to colonial intervention, Morocco thrived as a sovereign state, its roots tracing back to the Idrisid dynasty of the 8th century, its rulers claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad. Under Sultan Moulay Hassan I, who ruled from 1873 to 1894, the kingdom stood as a bastion of independence in the Maghreb. Its markets in Fez and Marrakech teemed with trade—leather, spices, and grain flowed to Europe and sub-Saharan Africa—while its Berber and Arab tribes paid tribute to a monarchy steeped in Islamic legitimacy. Moulay Hassan modernized his army with rifles and artillery, crisscrossing the realm to quell revolts and assert control, his court a blend of tradition and pragmatism. Morocco prospered as a land of diversity and resilience, its sovereignty a shield against the growing shadow of Europe.

The French and Spanish arrival eroded this independence. Drawn by Morocco’s strategic position and resources—phosphates, agriculture, and access to the Mediterranean—they circled the kingdom like predators, their influence seeping through trade and diplomacy. Moulay Hassan I faced these pressures with a deft hand, resisting outright domination while navigating a world tilting toward colonial rule. He welcomed European advisors to strengthen his military yet rebuffed their demands for concessions, traveling his realm to rally tribal loyalty and maintain unity. His reign saw a delicate dance of diplomatic resistance—treaties signed with Britain and Spain preserved Morocco’s nominal autonomy, while his refusal to bow to French ambitions kept the kingdom free longer than its neighbors. Yet the forces arrayed against him grew stronger, their patience thinning as the 19th century waned.

The end came after his death, culminating in 1912. Moulay Hassan’s successors—Moulay Abdelaziz and Moulay Hafid—lacked his skill, facing internal strife and mounting European pressure. France, exploiting Morocco’s debts and unrest, imposed a protectorate in March 1912 under the Treaty of Fez, reducing the sultan to a figurehead. Spain claimed the north and south, carving up the kingdom between them. The diplomatic resistance Moulay Hassan I had waged—holding off colonization through shrewd negotiation—crumbled as his heirs succumbed to a tide he could not stem. The French and Spanish divided Morocco’s spoils, their flags rising over a land that had defied them for decades.

Morocco, a kingdom of dynastic pride and trade, fell under foreign dominion. Its markets served new masters, its tribes subdued by colonial decrees. Sultan Moulay Hassan I’s diplomatic resistance delayed the inevitable, a testament to a ruler who fought with words as well as weapons. Yet the protectorates of 1912 marked the end of an era, a stark reminder of a time when Morocco stood tall—its greatness dimmed when the white man came with treaties and triumph.

Smaller Kingdoms and Societies

Beyond the great empires and renowned kingdoms of Africa, a constellation of smaller states and societies thrived across the continent, their resilience and diversity a testament to a rich precolonial tapestry before European domination swept them away. These polities—some centralized, others diffuse—flourished in forests, deltas, and highlands, their economies tied to local trade, agriculture, and craftsmanship. From the riverine towns of the Niger Delta to the highlands of Cameroon, these communities governed themselves with ingenuity, their leaders wielding authority rooted in tradition and adaptation. The arrival of colonial powers disrupted this mosaic, their superior weaponry and cunning overwhelming even the smallest bastions of independence. This section explores a selection of these lesser-known realms and resistance movements:

- Itsekiri Kingdom – A Niger Delta trading state in present-day Nigeria.

- Bamum Kingdom – A creative highland realm in present-day Cameroon.

- Lozi Kingdom – A floodplain power in present-day Zambia.

- Ekumeku Resistance – An Igbo uprising in present-day Nigeria.

- Yoruba City-States – A network of urban powers in present-day Nigeria.

Itsekiri Kingdom

In the labyrinthine waterways of the Niger Delta, now part of Nigeria, the Itsekiri Kingdom thrived as a maritime trading state before British encroachment drowned its sovereignty.

15th century under the Olu dynasty, the Itsekiri Kingdom flourished as a bustling hub of commerce, its coastal town of Warri alive with the trade of fish, salt, and palm oil. Canoes darted through the delta’s channels, ferrying goods to markets along the West African coast and beyond. The kingdom’s rulers, adorned with coral beads and wielding authority from a palace overlooking the Benin River, oversaw a sophisticated society that blended fishing, trade, and diplomacy with neighboring states like Benin and Oyo. Its people crafted intricate boats and wove nets, their lives tied to the tides and the bounty of the delta. Under leaders like Olu Ereju and later Nana Olomu in the 19th century, the Itsekiri prospered, their wealth measured in oil barrels and their independence secured by a fleet of war canoes that patrolled the waters. The kingdom stood as a vibrant nexus of trade and culture, its autonomy a quiet strength in a region of shifting powers.

The British arrival shattered this thriving realm. Drawn by the palm oil riches of the Niger Delta and intent on dominating West African trade, the Royal Niger Company set its sights on the Itsekiri by the late 19th century. Initially, the kingdom navigated these newcomers with caution, striking deals to maintain its middleman role in the oil trade. Nana Olomu, who rose to prominence in the 1880s, fortified Warri with cannon-armed canoes and resisted British demands for monopoly control, his defiance a bulwark against encroaching domination. Yet the British, armed with steamships and Maxim guns, would not be deterred. In 1891, they imposed a protectorate over the Oil Rivers, pressuring Nana to bow to their terms. His refusal sparked a brutal response—in 1894, a British expedition attacked Warri, bombarding the town with artillery and razing its defenses. Nana held out for months, but the onslaught proved overwhelming; he surrendered and was exiled to Lagos, then Accra, his kingdom stripped of its ruler.

The Itsekiri Kingdom crumbled under British rule. Once alive with local trade, its waterways became conduits for colonial profit, and its markets redirected to London’s coffers. The Olu title persisted, but as a shadow of its former power, subordinated to colonial administrators. Warri’s wooden palaces decayed, its canoes stilled, its people pressed into labor for a distant empire. Nana Olomu’s exile in 1894 marked the end of an era, a poignant fall for a state that had thrived on its wits and waters. Once a proud trading hub, the Itsekiri Kingdom faded—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with guns and greed.

Bamum Kingdom

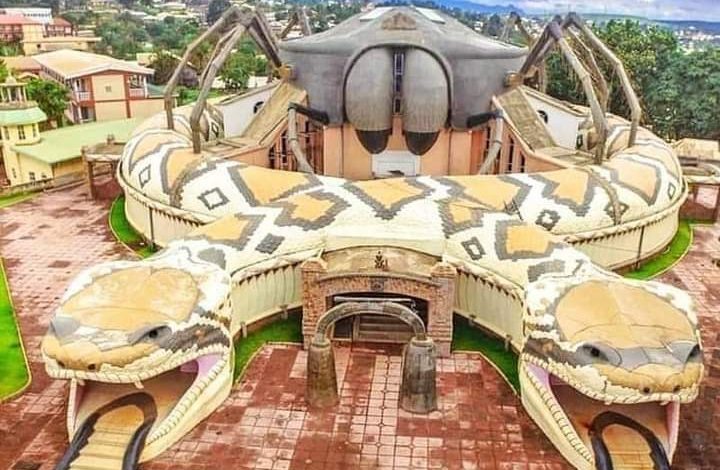

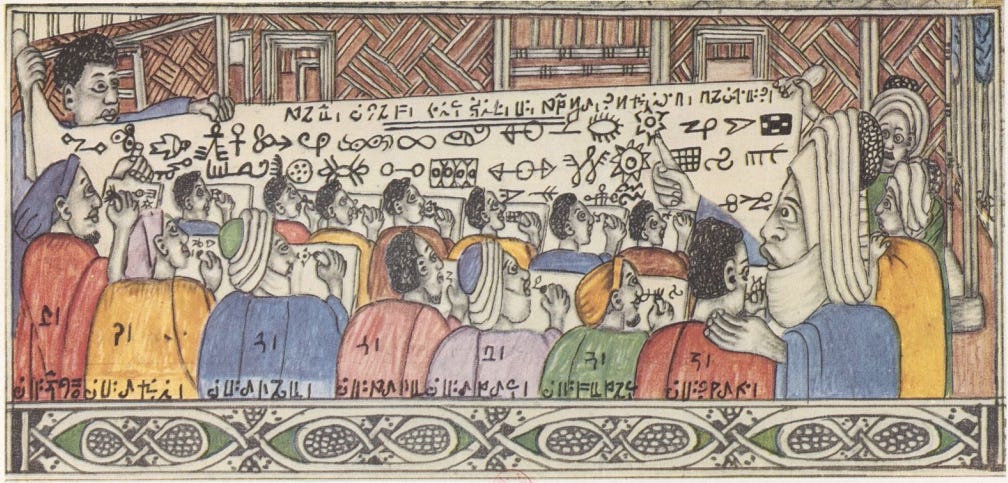

In the grassy highlands of what is now Cameroon, the Bamum Kingdom thrived as a creative and dynamic realm before German and French colonial forces smothered its brilliance. Established in the 14th century by the Bamum people, the kingdom reached its zenith under King Njoya, who ruled from 1884 to 1931. Prior to European intrusion, Bamum flourished as a center of innovation and culture, its capital at Foumban a bustling hub of art and agriculture. The kingdom’s fields yielded coffee, yams, and millet, traded across the Grassfields region, while its artisans crafted intricate masks and bronze sculptures that adorned the royal palace. Njoya, a visionary leader, elevated Bamum’s legacy by inventing the Bamum script around 1896—a syllabary of over 500 characters—transforming oral traditions into written records. His court boasted a library, schools, and a printing press, blending tradition with progress. The kingdom stood as a beacon of creativity and self-reliance, its people proud of a ruler who bridged past and future.

The German arrival shattered this vibrant era. Drawn by Cameroon’s resources and strategic position, Germany claimed the region in 1884, its colonial ambitions clashing with Bamum’s autonomy. Initially, Njoya navigated this threat with diplomacy, welcoming German traders and missionaries to secure firearms and allies against rival kingdoms like the Fulani. His palace grew grander, its walls painted with historical murals, a symbol of Bamum’s resilience. Yet German patience waned—by 1902, they demanded full submission, sending troops to Foumban to enforce their rule. Njoya resisted subtly, preserving his script and culture while feigning cooperation, but the balance tipped after Germany’s defeat in World War I. France took over Cameroon in 1916, viewing Njoya’s innovations as a challenge to their authority. In 1931, they deposed him, exiling him to Yaoundé, where he died two years later, his kingdom stripped of its king and its spirit.

The Bamum Kingdom faded under colonial weight. Its script fell into disuse, its fields repurposed for French plantations, its palace left to decay as a relic of a lost age. Njoya’s exile marked the end of an era of creativity, his printing press silenced, his people subjected to foreign laws. Once a highland realm where art and intellect thrived, Bamum succumbed—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with rifles and rigid rule.

The Fon Kingdom of Bafut

In the verdant Grassfields of what is now Northwest Cameroon, the Bafut Kingdom thrived as a proud and powerful fondom, its legacy stretching back over four centuries before European colonial forces dimmed its glory. Founded in the late 16th century by a Tikar prince who migrated south from the Adamawa region, Bafut grew into a centralized state under the rule of its Fon, a king revered as both a political and spiritual leader. Before the white man’s shadow fell, the kingdom flourished around its capital, Bafut, a bustling center of trade and culture. Its people cultivated yams, maize, and palm oil in the fertile highlands, their markets alive with the exchange of cloth, beads, and iron tools forged by skilled smiths. The Fon’s palace, a sprawling complex of over fifty buildings, stood as a testament to Bafut’s wealth, its Achum shrine—carved from wood and bamboo—housing ancestral spirits consulted for every major decision. The kingdom’s warriors, armed with spears and shields, enforced order, while secret societies like the Kwifor advised the Fon, their masked rituals weaving tradition into governance. Bafut stood as a beacon of autonomy and ingenuity, its people united under a ruler whose word was law, their lives enriched by a harmony of land and custom.

The European arrival unraveled this vibrant realm, bringing not just conquest but the plunder of its cultural soul. Portugal’s ships brushed Cameroon’s coast in the 15th century, but it was Germany’s colonial grip in 1884 that struck Bafut directly. Drawn by the region’s agricultural potential and strategic position, the Germans declared Kamerun a protectorate, their ambition clashing with the Grassfields’ independent fondoms. Under Fon Abumbi I, Bafut resisted fiercely. From 1901 to 1907, the Bafut Wars raged as German troops, armed with rifles and artillery, clashed with Bafut warriors. Early battles favored the kingdom, its rugged terrain a shield against invaders, but German firepower prevailed. In 1907, a punitive raid torched the palace, including the sacred Achum shrine, leaving scars on Bafut’s spirit. Beyond physical destruction, the Germans pillaged cultural treasures across the Grassfields—most infamously, the Ngonnso statue, a sacred wooden figure of the Nso people’s founding queen, seized in 1902 from Kumbo by colonial officer Kurt von Pavel. Though taken from neighboring Nso, its capture reverberated through Bafut and beyond, a stark theft of heritage that symbolized the broader looting of identity, its absence a wound felt in every fondom’s rituals.

The British succession after World War I deepened Bafut’s decline. In 1916, following Germany’s defeat, Bafut fell under British Cameroons, ruled from Lagos as part of a League of Nations mandate. Fon Achirimbi II, succeeding his father in 1910, faced a subtler erosion—British indirect rule preserved the Fon’s title but hollowed his power, turning him into a colonial intermediary. The Ngonnso’s loss lingered as a grim reminder, its empty place in Grassfields lore mirrored by Bafut’s own diminished sovereignty. British administrators imposed taxes and redirected trade, siphoning the kingdom’s wealth to distant coffers. The palace rose again, rebuilt with stone and thatch, but its grandeur masked a fading autonomy; the Kwifor’s influence waned, and the annual Abin e Mfor dance became a spectacle rather than a celebration of power. When Cameroon gained independence in 1961, uniting British and French territories, Bafut’s Fon retained ceremonial stature under a modern government, but true independence was lost. The kingdom, once a thriving highland power, faded—its fields exploited, its traditions diluted, its sacred Ngonnso stolen, its greatness extinguished when the white man came with fire and theft.

Lozi Kingdom

In the floodplains of the Upper Zambezi, now part of Zambia, the Lozi Kingdom thrived as a masterful floodplain power before British colonial ambition submerged its sovereignty. Established in the 17th century by the Luyi people under the Litunga—the king—the Lozi transformed the seasonal inundation of the Barotse Floodplain into a source of strength. Prior to European interference, the kingdom flourished through a unique adaptation: each year, as waters rose, the Litunga led a ceremonial migration, the Kuomboka, from the flooded plains to higher ground, his ornate barge a symbol of unity and resilience. The Lozi cultivated sorghum and fished the Zambezi’s bounty, while their vast cattle herds grazed the dry season pastures, a wealth that underpinned trade with neighbors like the Tonga and Shona. Barotseland, as it was known, hummed with activity—villages of stilted huts dotted the landscape, and the royal capital at Lealui hosted courts and markets. Under Litunga Lewanika, who ruled from 1878 to 1916, the kingdom stood as a testament to ingenuity and independence, its people in harmony with a river that shaped their lives.

The British arrival unraveled this resilient realm. Drawn by Southern Africa’s minerals and the strategic lure of the Zambezi, Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company (BSAC) eyed Barotseland as a stepping stone for their Cape-to-Cairo vision. Lewanika, a forward-thinking ruler, initially sought European alliance to protect his kingdom from Portuguese and Ndebele threats, sending envoys to negotiate with the BSAC. In 1890, he signed the Lochner Concession, misled by assurances it was a protective treaty granting limited mining rights. The document, cloaked in vague promises, instead ceded vast control to the British, a deception Lewanika only later grasped. By 1897, British agents arrived in Lealui, imposing taxes and undermining the Litunga’s authority, their presence a creeping betrayal of the trust he had extended.

The kingdom’s fall solidified over decades. Lewanika resisted where he could, petitioning Queen Victoria in 1902 to clarify the treaty’s terms, but British responses reaffirmed their dominance. The BSAC absorbed Barotseland into Northern Rhodesia, formalized in 1911, reducing the Litunga to a ceremonial figure under colonial oversight. The floodplain’s rhythms continued—the Kuomboka persisted—but its meaning hollowed out, a spectacle for foreign eyes rather than a celebration of Lozi power. The kingdom’s cattle were taxed, its trade redirected, its people pressed into labor for British projects. Lewanika died in 1916, his legacy overshadowed by a colonial system that exploited his diplomacy. The Lozi Kingdom, once a floodplain power of adaptability and pride, faded—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with false words and iron rule.

Ekumeku Resistance

In the forested hinterlands of what is now Nigeria’s Anioma region, the Igbo societies of the Western Igbo thrived as a network of villages before British colonial rule crushed their autonomy. Prior to European interference, these communities flourished under a decentralized system of governance, their councils of elders and age-grades maintaining order without kings. Yam farms stretched across the landscape, their harvests sustaining a robust economy alongside palm oil trade that flowed through markets like Asaba and Onitsha. The Igbo here were skilled craftsmen, forging iron tools and weaving cloth, their lives enriched by masquerades and oral traditions that bound them to their ancestors. Secret societies, like the Ekumeku, served as cultural and defensive pillars, their rituals and oaths fostering unity among the clans. This region prospered in a state of self-reliance and resilience, its people free from foreign dominion, their independence a quiet strength in the face of a changing world.

The British arrival shattered this harmony. Drawn by the Niger Delta’s riches and intent on controlling southern Nigeria, the Royal Niger Company imposed its presence in the 1880s, followed by formal British rule after the 1891 Oil Rivers Protectorate. Taxes, forced labor, and Christian missions disrupted Igbo traditions, sparking resentment. The Ekumeku, originally a cultural society, transformed into a resistance movement by 1898, its warriors—armed with machetes, spears, and a few muskets—vowing to expel the invaders. From 1898 to 1911, the Ekumeku Resistance waged a guerrilla war across the Anioma region, striking British outposts and collaborators from the cover of dense forests. Their tactics—ambushes, night raids, and sabotage—frustrated colonial efforts, a testament to a people unwilling to bow to foreign decrees.

The struggle peaked between 1902 and 1904, with the Ekumeku War reaching its height. In 1902, warriors besieged Ogwashi-Uku, a key British base, holding it for weeks before artillery and reinforcements turned the tide. The British responded with punitive expeditions, burning villages and executing leaders to break the resistance. By 1911, after years of relentless campaigns, the Ekumeku faltered—its fighters overwhelmed by Maxim guns and colonial troops, its strongholds razed. The final blow came with the capture and execution of key leaders, their exile or death signaling the end of the uprising. The Western Igbo lands fell under British control, incorporated into the Southern Nigeria Protectorate, their autonomy extinguished, their people subjected to taxes and foreign laws.

The Ekumeku Resistance, a fierce stand for Igbo independence, faded into the shadows of colonial rule. Its yam fields fed British coffers, its forests stripped for plantations, its traditions suppressed by missionary zeal. The uprising, spanning over a decade, marked a desperate bid to preserve a way of life, its defeat a bitter testament to resilience overwhelmed. Once a society of self-governance and pride, the Anioma Igbo succumbed—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with steel and subjugation.

Yoruba City-States

In the forested southwest of what is now Nigeria, the Yoruba City-States thrived as a network of urban powers before British colonial rule dismantled their sovereignty. Emerging centuries ago, this constellation of kingdoms—Oyo, Ibadan, Ife, Ijebu, and others—formed a sophisticated civilization, each city a hub of trade, culture, and governance. Prior to European interference, the Yoruba lands buzzed with activity: Oyo, the historic hegemon, commanded vast trade routes with kola nuts, cloth, and salt, its Oba ruling through a council of chiefs; Ife, the spiritual cradle, gleamed with terracotta art and bronze castings; Ibadan rose as a martial power, its warriors guarding fertile plains; and Ijebu controlled coastal commerce with European traders. Markets thrived with yams, palm oil, and crafted goods, while artisans wove intricate textiles and blacksmiths forged tools. The Yoruba governed through a blend of monarchies and councils, their cities fortified with mud walls, their society enriched by orisha worship and oral histories. This network stood as a testament to urban ingenuity and cultural depth, its independence a vibrant mosaic of power and pride.

The British arrival shattered this flourishing realm. Drawn by Nigeria’s resources and eager to secure the coast, they crept into Yoruba lands in the mid-19th century, their missionaries and traders softening the ground for conquest. Initial contact brought trade—guns and cloth exchanged for palm oil—but soon morphed into control. By the 1850s, Britain annexed Lagos, an Ijebu outpost, sparking tensions with the interior states. The Yoruba, riven by internal wars like the 19th-century Oyo collapse and Ibadan-Ijebu conflicts, faced a cunning foe exploiting these divisions. In 1892, the British bombarded Ijebu-Ode after its king, the Awujale, resisted their demands, crushing its defenses with artillery. Oyo’s Alaafin and Ibadan’s Bashorun capitulated under pressure, signing treaties that eroded autonomy. By 1893, the British declared the Southern Nigeria Protectorate, imposing indirect rule that reduced Obas to colonial puppets, their councils overridden by foreign dictates.

The final blow came with systematic subjugation. Resistant leaders, like the Alaafin of Oyo in the 1890s, were deposed or sidelined, their cities—once bustling with trade—turned into administrative outposts. The Yoruba wars of resistance, such as the 1895 Iseyin revolt, flared briefly but succumbed to British rifles and Maxim guns. By the early 20th century, the city-states lay fully under colonial control, their walls crumbling, their markets redirected to British profit. The Yoruba City-States, a network of urban brilliance, faded into the shadow of empire—its fields taxed, its traditions stifled, its Obas stripped of true power. Once a constellation of thriving powers, the Yoruba succumbed—its greatness extinguished when the white man came with guile and gunfire.

Conclusion