The REAL Reason African Masks Are More Than Just Art

You are not African, but for some reason, you own African masks. And the big question is: why?

People often reach out to me with stories like this. Someone who isn’t African receives a mask as a gift, keeps it, and turns it into decoration. I recently heard from someone named Justin who was given a beautiful mask as a gift. It was a distinctive Marka mask from Mali (most probably). It had been modified as a striking piece of home décor. It looks impressive, no doubt.

A Mask I Recognised Immediately

The moment I saw the pictures, I recognised it—not because I can identify every mask from across the continent (that would be impossible), but because this one is unique. I have seen one of these perform in the past. You see, there are African traditional masked performances you experience, and they are just basic. But then, some would stick with you for a lifetime. This was one of those.

There are thousands of African cultures, each creating masks with their own unique designs, names, stories, and purposes. Some share similarities within the same region, but they remain distinct. This particular Marka mask, like most are designed to be, carries the bull symbolism and prominently features horns. Those horns represent protection. To learn all about the significance of horns on African Masks, see the video below:

What the Mask Actually Does

The Marka mask serves multiple roles: it maintains social order, blesses fertility, radiates love and positive energy, and brings healing—not just to those who watch it perform, but to the entire community it was made for.

When worn in performance, the mask moves in swirling dances, touches people, lays hands on them, and imparts wellness, goodness, and blessings. It is a living conduit of spirit and community health. To get the fullest meaning and benefit from a Marka mask, you do not hang it on a wall. You put it on a person, let it dance, and allow it to do its work. A good point to make here is that African masks should never go on just any face. If you own masks, never put them on unless you have undergone some initiatory rites, but this is the subject of this article.

The proliferation of African masks across the world is an unfortunate reality. But we shall neither cry nor rant about that.

No One Is Entirely to Blame—But the Practice Is Still Wrong

I don’t blame the individuals who receive these masks as gifts. I don’t blame the buyers who think they’re purchasing art, nor even the dealers trying to make a living. And I know many Africans have been part of selling these pieces—sometimes out of financial need.

Masks were undeniably stolen on a massive scale a century ago during colonial raids, and that practice has continued in different forms. Dealers still pay substantial sums for masks with proven history and significance. Some people are even approached today and offered fortunes to remove ancestral masks from their communities.

But none of that changes the core issue: African masks belong with Africans, in Africa. Here’s one jarring truth you should know before you hang up the next one.

These Are Items of Worship

Not every African needs to own a mask, of course. Only those who understand their purpose, who can handle them respectfully and use them properly, should be their keepers. These are items of worship.

Every religion fiercely protects its sacred symbols. Imagine trying to walk into St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City and remove a consecrated crucifix or altar item. Imagine attempting to take a revered object from Mecca during Hajj. Imagine trying to carry away a historic relic from a sacred site in Israel. You would meet fierce resistance—and rightly so.

Yet African sacred symbols are routinely treated as tradeable art, passed around as gifts to people who do not understand what they are, what they are capable of, or how to care for them. This leads to desecration and abuse of spiritual material.

The Irony in How We Treat Sacred Objects

It’s ironic: many who reject Christianity would still hesitate to possess certain Christian sacred objects in a casual way. For instance, a non-Catholic owning a blessed statue of the Virgin Mary raises eyebrows. Buying a mass-produced crucifix in a shop is one thing; taking a consecrated one on an altar from a church is entirely another.

African masks, in many cases, are not generic replicas—they are the central figures in a community’s spiritual life.

What Happens When a Mask Is Taken Away

When a mask is removed, a chain is broken. Knowledge of its origin, history, significance, and proper use is lost to the people it was made for.

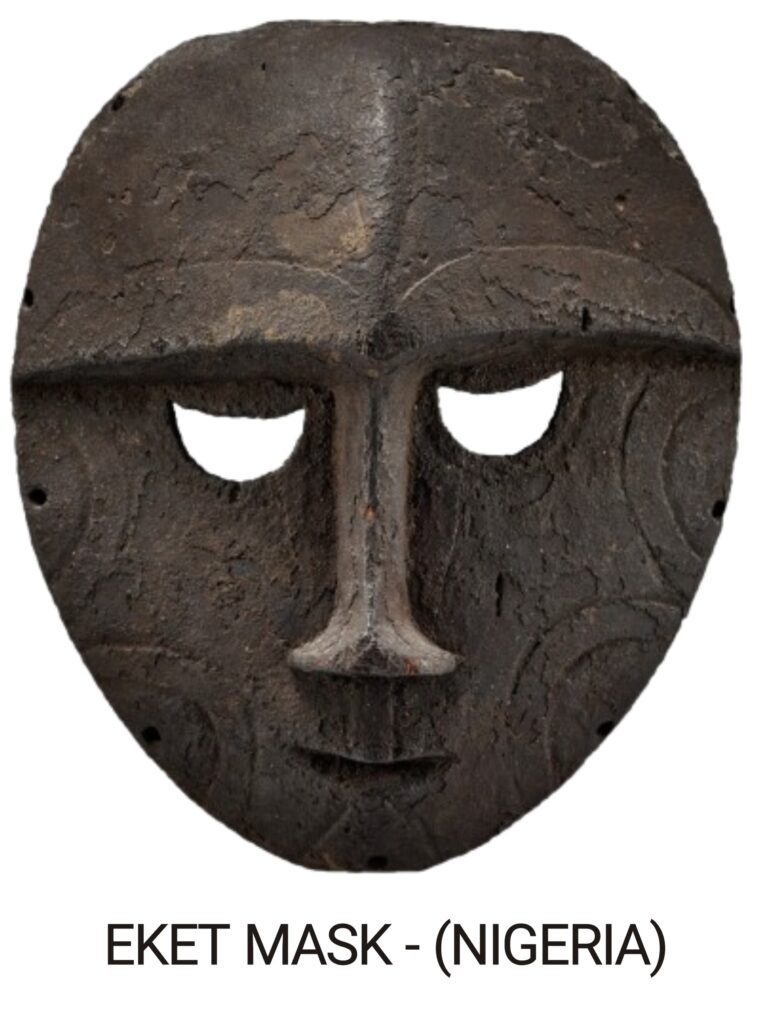

The Benin Kingdom Example

A clear example is the ancient Benin Kingdom in Nigeria. Over 120 years ago, thousands of bronze and ivory works—called “artefacts” by the British and Germans—were looted during a punitive expedition. The Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi was exiled, his palace raided, and the great Benin walls (longer than the Great Wall of China) burned to the ground.

For decades, there has been debate about returning those pieces. When returns seemed imminent a few years ago, there was even disagreement within Nigeria about who should house them: the Oba or a government museum.

The deeper problem is that those objects were never meant for museums. They had active roles in the lives of the people. Generations of disruption and cultural loss mean that even many contemporary Benin people would initially struggle to recall the full original uses of every piece.

But with genuine intent, spiritual consultation, and effort, that knowledge can be rediscovered. It won’t happen overnight, but it is possible.

Masks Belong Back Home—In Living Use

Whatever perspective you take, these masks belong back home in Africa—among Africans—not as mere commercial museum exhibits, but returned to the spiritual life of the people. They may still generate income, but that should never be their primary purpose.

Africans have been robbed for far too long. I’m not calling for monetary reparations in the form of billions paid to descendants of the enslaved or colonised.

But if you possess an African mask and you are not connected to its culture or spirituality, consider this: the right thing is to send it home.

How to Return It Properly

Don’t sell it—selling simply continues the cycle, often through dealers (including some Africans) who treat it as business.

Instead, return it to an institution on African soil where it will be protected and respected. Many African museums would welcome such donations with gratitude.

African masks are far more than art. They are living spiritual objects, bearers of history, healing, and community power. They belong where they can fulfil that purpose—back in Africa, in African hands.

If you need help with this, get in touch via my website or just shoot me an email: michael@sevics.africa