The Female Kings of Africa: 14 Warrior Queens Who Defied Gender Norms and Ruled Empires.

Did Africa have Female Kings?

History brims with tales of extraordinary female kings of Africa, women who shattered gender barriers to reign as kings—not just queens—commanding armies, forging empires, and leaving legacies that challenge Western assumptions about patriarchy in pre-colonial societies. These visionary leaders, from the Hausa city-states of Nigeria to the kingdoms of Angola, Kush, and beyond, redefined power and leadership in ways that resonate even today. In this article, we shall explore the lives of Africa’s most iconic female kings—Amina of Zaria, Ahebi Ugbabe, Orompoto of Oyo, Nzinga of Ndongo, the Kandakes of Kush, the Omu of Okpanam, and others—diving into their military brilliance, political strategies, and personal choices. We willl also uncover the co-rulerships that shaped their empires, offering a fresh perspective on gender and authority in African history.

1. The Omu of Okpanam and the Legacy of Anioma’s Female Kings

The Omu of Okpanam: A Spiritual and Market Sovereign

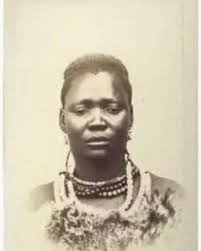

In the Enuani Igbo town of Okpanam, near Asaba in present-day Delta State, Nigeria, the Omu institution represents a unique tradition of female kingship dating back over 700 years. The Omu of Okpanam, a title meaning “female king” or “queen mother,” wielded authority over markets, women’s affairs, and spiritual rites, serving as a counterpart to the male Obi (king). One of the earliest recorded Omus of Okpanam was photographed in 1912 by anthropologist Northcote Thomas, adorned with a red cap, feathers, and beads—symbols of her chiefly status. Her role included opening markets, resolving disputes, and acting as a spiritual protector, often working in tandem with diviners to safeguard the community. Unlike many rulers, the Omu was typically postmenopausal and unmarried, sometimes taking wives to assist her and bear children in her name, reflecting a fluid approach to gender roles in pre-colonial Igbo society.

Obi Martha Dunkwu: The Modern Omu of Okpanam and Anioma

A contemporary example of this tradition is Obi Martha Dunkwu, who served as the Omu of Okpanam and later the Omu of Anioma until her death in 2023. Crowned in 2002 as Omu of Okpanam and in 2010 as Omu of Anioma (a title encompassing nine local government areas in Delta State), Dunkwu revitalized the Omu institution. A media practitioner educated in England and the United States, she brought global visibility to Anioma culture, increasing the number of active Omus from six to fifteen during her tenure. Forbidden from marrying men after her coronation, she lived in a palace built at her father’s home, embodying the dual male-female authority of the Omu. Her reign blended tradition with modernity, promoting tourism and cultural preservation until her passing, leaving a legacy as a bridge between past and present.

2. Amina of Zaria: The Warrior Queen Who Built an Empire

In the vibrant history of West Africa, Amina of Zazzau—known today as Zaria, Nigeria—stands as one of the most iconic female kings of Africa. Born in 1533, she ascended to the throne as Sarauniya (queen) in 1576, becoming the first woman to rule this Hausa city-state. Her reign, stretching until 1610, transformed Zazzau into a military and economic juggernaut, its influence radiating from the Niger River to the territories of modern-day Kano and Nupe. Amina, a warrior queen of unparalleled vision, defied gender norms and reshaped her world through conquest, innovation, and sheer will, earning her a lasting place among African women rulers whose legacies endure.

Rise to Power in a World of Trade and Warfare

Amina’s ascent came in an era when trade routes were the lifeblood of West African power. Born into Zazzau’s royal family, she was the daughter of King Nikatau and Queen Bakwa Turunku, who herself wielded influence in a male-dominated court. Trained in warfare from youth—Amina reportedly excelled with the sword and bow—she inherited the throne after her brother Karama’s death in 1576. At a time when salt, horses, and kola nuts fueled wealth and alliances, Amina seized the opportunity to expand Zazzau’s dominion, turning a regional player into a formidable empire.

Her reign was a masterclass in leveraging trade and warfare. Amina’s campaigns stretched Zazzau’s borders, securing vital trade networks that connected the Sahara to the forest zones. This economic expansion echoed the prosperity of Hatshepsut of Egypt, who enriched her realm through expeditions to Punt, or Amanishakheto of Kush, whose treasures reflected Kushite wealth. Amina’s leadership transformed Zazzau into a hub of commerce and power, her rise a testament to her ability to thrive in a world where strength and strategy reigned supreme.

Military Genius and Lasting Innovations

Amina wasn’t merely a ruler—she was a military visionary whose innovations reshaped warfare in the Hausa states. She introduced armored cavalry to Zazzau’s forces, equipping her warriors with quilted armor for horses and riders—a tactic that mirrored Orompoto of Oyo’s cavalry revival and gave her a decisive edge in the savannah. Her siege tactics were equally revolutionary, overwhelming enemies with relentless assaults that forced submission. Amina led these campaigns herself, clad in battle gear, her presence on the battlefield inspiring awe and fear.

Her conquests weren’t just about victory—they were about permanence. Amina fortified her gains with the ganuwar Amina, or “Amina’s walls”—mud-brick defenses encircling subjugated cities. These structures, still visible across northern Nigeria, stand as testaments to her engineering foresight, blending military strategy with civic innovation. Like Hangbe of Dahomey, who armed the Amazons, or Nzinga of Ndongo, who disrupted Portuguese slaving routes, Amina’s military genius left a tangible legacy, her walls a physical echo of her reign’s strength.

Defying Gender Norms with Bold Choices

In a society where marriage often tethered women to domestic roles, Amina charted a path of radical independence. She famously rejected permanent matrimony, declaring it a potential chain on her autonomy—a stance as bold as Ranavalona I’s solitary rule in Madagascar. Instead, oral traditions recount that she took temporary consorts, often defeated rulers, turning personal alliances into political victories. After a night with these men, legend claims she ordered their execution to ensure no rival could claim her power—a chilling assertion of dominance, though likely embellished by time.

This celibate warrior queen defied gendered expectations with every choice, aligning her with female kings of Africa like Nzinga, who kept a harem of male concubines, or Ahebi Ugbabe, who “married” wives in colonial Nigeria. Amina’s refusal to conform reshaped her image in Hausa culture, where she is celebrated in songs and stories as a sovereign who ruled by her own rules. Her face graces Nigeria’s 200-naira banknote, a modern tribute to a queen whose defiance remains a beacon of empowerment.

3. Ahebi Ugbabe: The Igbo Woman Who Became a King

In the annals of female kings of Africa, Ahebi Ugbabe stands as a singular and audacious figure—a warrior queen of intellect and ambition who rose from fugitive to monarch in colonial Nigeria. Born in Enugu-Ezike in the late 19th century, Ahebi fled her Igbo homeland as a teenager to escape a forced marriage, embarking on a journey that would see her reinvent herself as a trader, diplomat, and ultimately the Eze (king) of her people. Mastering the art of survival and influence, she shattered Igbo gender norms with colonial backing, ruling in a way that defied tradition and reshaped her community. Ahebi’s story, ending with her death in 1948, is a complex tapestry of triumph and tension, cementing her place among African women rulers who redefined power on their own terms.

From Fugitive to Unprecedented Monarch

Ahebi’s extraordinary ascent began with an act of defiance. Fleeing Enugu-Ezike to avoid a betrothal she rejected, she sought refuge in Igala territory, north of her Igbo homeland. There, she transformed adversity into opportunity, learning the Igala language and leveraging her skills as a trader and courtesan to build wealth and connections. Her shrewd diplomacy earned her the favor of the Igala king and, crucially, British colonial officials, who were expanding their influence in Nigeria during the early 20th century. This alliance provided Ahebi with the resources and authority to return home—not as a prodigal daughter, but as a power broker.

Back in Enugu-Ezike around the 1910s or 1920s, Ahebi didn’t merely reclaim her place; she upended the social order. With British support, she declared herself Eze—a title reserved exclusively for male kings in Igbo culture—establishing a reign that defied centuries of tradition. Her rise mirrors the audacity of female kings of Africa like Orompoto of Oyo, who bared her resolve to silence doubters, or Nzinga of Ndongo, who adopted male titles to assert dominance. Ahebi’s journey from fugitive to monarch was a testament to her ingenuity, turning exile into a springboard for unprecedented power.

Shattering Igbo Traditions

Ahebi’s rule was a radical departure from Igbo norms, blending traditional authority with colonial innovation. Donning men’s attire and performing male rituals, she embodied the kingship she claimed, much like Hangbe of Dahomey or Hatshepsut of Egypt, who used masculine symbols to reinforce their rule. In a stunning inversion of gender roles, Ahebi “married” wives, assigning them surrogate husbands to bear children in her name—a practice that asserted her supremacy while echoing Nzinga’s harem of male concubines dressed as women. Her court became a bustling hub of commerce, dispute resolution, and governance, merging Igbo customs with the administrative framework of British indirect rule.

Her reign brought prosperity to Enugu-Ezike, as trade flourished and her influence stabilized the region under colonial oversight. Yet Ahebi’s power was not just economic—it was cultural. By claiming the Eze title, she shattered the gendered boundaries of Igbo leadership, proving that authority could be wielded by a woman with the vision and will to redefine it. Her story aligns with African women rulers like Queen Idia of Benin, who blended martial and maternal roles, or Ranavalona I of Madagascar, who enforced her own brand of sovereignty. Ahebi’s court was a bold experiment, a bridge between tradition and the colonial era.

A Complex and Controversial Legacy

Ahebi Ugbabe’s reign, though transformative, was not without cost. Her collaboration with the British—strategic for her rise—alienated many in Enugu-Ezike, who saw her as a pawn of colonial power rather than a liberator. Her imposition of taxes and enforcement of British policies stirred resentment, creating a divide between her prosperity and her people’s loyalty. By the time of her death in 1948, Ahebi’s legacy was a paradox: a trailblazer who brought wealth and order, yet a ruler whose reliance on external influence left her estranged from her roots.

Today, historians and storytellers view Ahebi as a pioneer who defied gender norms, her life immortalized in literature, plays, and screen depictions. Works like Nwando Achebe’s The Female King of Colonial Nigeria bring her story to light, celebrating her as a symbol of resilience while grappling with the tensions of her colonial ties. Her legacy parallels that of female kings of Africa like Ndaté Yalla Mbodj, whose resistance delayed French domination, or Yaa Asantewaa, whose rebellion inspired future generations. Ahebi’s reign underscores the delicate balance between tradition and external forces, a complexity that enriches her place in history.

4. Orompoto of Oyo: The Female Alaafin Who Rescued an Empire

In the storied history of the Oyo Empire, Orompoto emerges as a towering figure among female kings of Africa—a warrior queen who ascended the throne in the 16th century to rescue her realm from collapse. Known as the Alaafin, or ruler, of Oyo in what is now southwestern Nigeria, Orompoto stepped into power during a time of crisis, facing invasions from the Nupe and internal discord that threatened to unravel the empire. Her reign, marked by military mastery and unyielding resolve, turned the tide for Oyo, laying the foundation for its 17th-century golden age. As one of the most enigmatic African women rulers, Orompoto’s legacy is a testament to leadership defined not by gender, but by courage and capability.

Stepping Up Amid Crisis

Orompoto’s rise to power came at a moment when the Oyo Empire teetered on the brink. The Nupe, a rival power from the north, had launched devastating raids, exploiting Oyo’s vulnerabilities after years of internal strife. Historical accounts place her reign around the mid-16th century, following the death of her brother, Alaafin Onigbogi, whose rule had ended in exile. As a woman claiming the throne, Orompoto faced skepticism from the royal council and nobles accustomed to male rulers. Legend recounts her bold response: baring her body before the council, she declared, “I may be a woman, but I have the heart of a king.” This audacious act silenced doubters and rallied her people, cementing her legitimacy as Alaafin.

Her ascent echoes the defiance of female kings of Africa like Nzinga of Ndongo, who adopted male titles to assert authority, or Hangbe of Dahomey, who donned kingly garb amid a succession crisis. Orompoto’s resolve transformed her from a questioned claimant into a unifying force, stepping up when Oyo needed a leader most. Her reign was not just a response to the crisis—it was a redefinition of what rulership could be.

Reviving Oyo Through Military Mastery

Orompoto’s genius lay in her military leadership, which breathed new life into the Oyo Empire. Recognizing the strategic advantage of the savannah terrain, she revitalized Oyo’s cavalry, leveraging horses—a rarity in West Africa at the time—to dominate the battlefield. Clad as a warrior, she led her troops into combat against the Nupe, turning the tide of invasion with swift, decisive victories. Her mastery of mounted warfare not only repelled external threats but also restored order within Oyo’s fractious domains, stabilizing the empire at a critical juncture.

Legends claim Orompoto met her end on the battlefield, a martyr whose sacrifice underscored her commitment to her people. Whether true or embellished, this tale reflects her reputation as a warrior queen who lived and died for Oyo’s survival. Her military reforms set the stage for the empire’s expansion and prosperity in the 17th century, a golden age built on the foundation she forged. Her victories align her with African women rulers like Amanirenas of Kush, who sacked Roman-held Aswan, or Mmanthatisi of the Tlokwa, who led her people through chaos—each a testament to the power of martial leadership in times of peril.

A Ruler Focused on Power, Not Partnership

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Orompoto’s personal life remains a cypher, with historical records rarely mentioning a consort or co-ruler. This absence suggests she ruled solo, prioritizing military and administrative reforms over traditional domestic roles. While queens like Nzinga co-ruled with her sister Kambu or the Kandakes partnered with their heirs, Orompoto appears to have stood alone, her authority unshared and absolute. This focus on power over partnership sets her apart, highlighting a reign defined by action rather than alliance.

Her solitary rule mirrors the independence of Ranavalona I of Madagascar, who dominated her son’s pro-European leanings, or Amina of Zazzau, whose conquests needed no consort’s support. Orompoto’s legacy proves that leadership, not gender or marital ties, was the cornerstone of her success. By reviving Oyo’s military might and stabilizing its governance, she carved a path that defied expectations, leaving a mark as enduring as it is mysterious.

5. Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba: The Diplomat-King Who Defied Colonialism

Nzinga of Ndongo: A Fierce Stand Against Portuguese Domination

In the annals of female kings of Africa, Nzinga Mbande of Ndongo and Matamba stands as a colossus—a warrior queen whose 40-year war against Portuguese colonizers in the 17th century defined her as one of the most formidable African women rulers. Rising to power in modern-day Angola, Nzinga adopted male titles, donned kingly attire, and led armies with a ferocity matched only by her diplomatic brilliance. Her reign, spanning from the 1620s until her death in 1663, was a masterclass in resistance, blending military might with strategic alliances to preserve her kingdoms’ sovereignty. Nzinga’s legacy as an anti-colonial icon endures, her name celebrated in Angola and beyond as a symbol of unyielding defiance.

A Fierce Stand Against Portuguese Domination

Nzinga’s reign unfolded during a perilous era for Ndongo, as Portuguese forces sought to expand their slave trade and colonial grip in West Central Africa. Born around 1583 into the royal family of Ndongo, she emerged as a leader in the 1620s, initially as a diplomat negotiating with the Portuguese on behalf of her brother, Ngola Mbande. But when he died in 1624—possibly by suicide amid mounting pressures—Nzinga seized the throne, rejecting Portuguese puppet rulers and declaring herself king. She adopted the title “Ngola,” a traditionally male role, and dressed in warrior garb, embodying the authority of a sovereign ruler.

Her war against the Portuguese was relentless. Leading armies with unmatched ferocity, Nzinga struck at colonial outposts, disrupted slave-trading routes, and offered sanctuary to Africans fleeing Portuguese enslavement. Her diplomatic genius shone in 1640s alliances with the Dutch, leveraging their rivalry with Portugal to bolster her forces. This echoes the defiance of female kings of Africa like Ranavalona I of Madagascar, who expelled European missionaries, or Amanirenas of Kush, who forced Rome into a treaty. Nzinga’s 40-year campaign kept the Portuguese at bay, preserving Ndongo and later Matamba as bastions of resistance until her final days.

Co-Rulership and Unconventional Authority

Nzinga’s rise to power was intertwined with her family, yet she carved a path of singular dominance. Initially co-ruling with her brother Ngola Mbande, she assumed full control after his death, navigating succession disputes with ruthless precision—some accounts suggest she eliminated rivals, including a nephew, to secure her throne. Her reign gained depth through her partnership with her sister Kambu (later known as Dona Barbara), whom she appointed as co-regent of Matamba. This alliance, akin to the Kandakes’ co-rulership with their heirs or Queen Idia’s with her son Esigie, strengthened Nzinga’s grip on power, blending familial loyalty with strategic governance.

Her authority was as unconventional as it was bold. To assert her supremacy, Nzinga maintained a harem of male concubines, dressing them as women—a provocative inversion of gender norms that underscored her kingly status. This mirrored Hangbe of Dahomey’s adoption of male attire or Ahebi Ugbabe’s rule as a warrant chief, placing Nzinga among African women rulers who redefined leadership. Her co-rulership with Kambu and her unorthodox court were not mere eccentricities but calculated displays of power, ensuring her enemies—both foreign and domestic—knew she ruled without equal.

A Legacy of Resistance

Nzinga’s tireless resistance bore fruit in the treaties she negotiated with Portugal, notably in 1657, which recognized Matamba’s sovereignty and curbed Portuguese aggression during her lifetime. These agreements, secured after decades of war and diplomacy, delayed full colonial domination of Angola until after her death on December 17, 1663, at age 80. Her passing marked the end of an era, but her influence lived on—Matamba remained a refuge for the enslaved, and her strategies inspired later anti-colonial movements.

Today, Nzinga is an Angolan icon, her story taught in schools, celebrated in festivals, and honoured with statues and street names. She is revered as a symbol of resilience, her defiance against Portuguese domination a cornerstone of national pride. Her legacy aligns with female kings of Africa like Yaa Asantewaa, whose rebellion slowed British rule, or Ndaté Yalla Mbodj, whose letters defied French conquest. Nzinga’s blend of military might, diplomatic savvy, and cultural assertion marks her as a titan among warrior queens, her reign a testament to the power of resistance.

Nzinga Mbande stands as a beacon of anti-colonial strength. Her 40-year war, her treaties, and her audacious court challenge us to rethink power—not as a gift of tradition, but as a force claimed through strategy and sacrifice. In the broader tapestry of African women rulers, she is a flame that burns bright—a warrior queen whose legacy inspires generations to resist, to rule, and to remember the women who forged empires against all odds. Nzinga’s story is not just Angola’s—it is Africa’s, a clarion call to honour the fierce sovereigns who refused to bow.

6. The Rain Queens of Balobedu: The Mystical Monarchs of Southern Africa

A Matrilineal Dynasty Rooted in Rainmaking

The Rain Queens, known as the Modjadji, have ruled the Balobedu people of South Africa’s Limpopo Province since at least 1800, with origins tracing back to the 16th century in what is now southeastern Zimbabwe. This hereditary monarchy stands out as a rare matrilineal system in Africa, where the throne passes exclusively from mother to eldest daughter, barring men from rulership. The first Rain Queen, Modjadji I, established this lineage, leveraging her reputed ability to control rainfall—a power so vital in a drought-prone region that it elevated her to king-like status among her people and beyond.

Power Through Mystique and Diplomacy

Unlike warrior queens like Amina or Nzinga, the Rain Queens wielded authority through spiritual sovereignty rather than military might. Modjadji I governed a small, peaceful tribe, using the “politics of mystique” to command respect from neighbouring powers. Leaders like Zulu King Shaka sent emissaries with gifts—such as black cattle—to request rain, fearing her ability to withhold it or curse enemies with drought. This ecological influence parallels the diplomatic finesse of Nzinga, showcasing a different facet of leadership that defied traditional gender roles by centering on life-giving power.

Defying Norms in Ritual and Succession

The Rain Queens’ personal lives further aligned them with Africa’s gender-defying rulers. Forbidden from marrying men in the conventional sense, they took “wives” from subject villages—women chosen by the Royal Council to serve as attendants and diplomatic envoys, not romantic partners. This practice echoes Ahebi Ugbabe’s marriages and Nzinga’s unconventional harem. To preserve their sacred lineage, believed to carry rainmaking powers through matrilineal DNA, they bore children with close relatives. Their current succession dispute—between Princess Masalanabo Modjadji (recognized by the South African government as Modjadji VII) and her brother Prince Lekukela (installed by the Royal Council in 2022)—reflects ongoing tensions as of March 23, 2025, yet underscores their enduring relevance.

A Legacy of Cultural and Ecological Influence

The Rain Queens’ influence persists in modern South Africa, where their royal compound and the Modjadji Cycad Reserve draw tourists, much like Amina’s walls attract visitors in Nigeria. Recognized by the government in 2016 after years of diminished status under apartheid, their legacy blends tradition with contemporary significance. As female kings, the Modjadji queens offer a unique lens on leadership—one where spiritual authority and matrilineal succession challenged patriarchal norms, enriching the tapestry of Africa’s ruling women.

7. The Kandakes of Kush: Africa’s Earliest Warrior-Queens

In the ancient kingdom of Kush, centered in Meroë (modern-day Sudan), the Kandakes—or Candaces—reigned as female kings of Africa, their power unrivalled and their legacy enduring. From the 1st century BCE to the 4th century CE, these warrior queens ruled not as consorts but as sovereigns in their own right, commanding armies, forging treaties, and shaping a civilization that rivalled the might of Rome. Among them, Amanirenas stands tallest, leading Kushite forces against Roman legions in 24 BCE and securing a peace that preserved her kingdom’s independence. The Kandakes, including figures like Amanishakheto, blended martial prowess with cultural grandeur, cementing their place among the most formidable African women rulers in history.

Sovereigns of a Mighty Kingdom

The Kandakes of Kush emerged during a golden era for the Meroitic kingdom, which thrived along the Nile after the decline of Egypt’s New Kingdom. Unlike queens in many contemporary societies, who derived power through marriage, the Kandakes held supreme authority as sovereign rulers. Their title, “Kandake,” denoted a queen regnant, a status that set them apart from mere regents or consorts. This tradition of female kingship reached its zenith with Amanirenas, who co-ruled with her son, Prince Akinidad, in the late 1st century BCE.

Amanirenas’ reign became legendary during her confrontation with Rome. In 24 BCE, as Roman forces under Emperor Augustus pushed south into Kushite territory, she led a daring counteroffensive. Her armies sacked the Egyptian city of Aswan, even toppling statues of Augustus—one of whose bronze heads, now in the British Museum, was buried beneath her palace steps as a symbol of defiance. Blinded in one eye during battle, Amanirenas pressed on, securing a favorable peace treaty with Rome that freed Kush from tribute and preserved its autonomy. Her leadership echoes the resilience of female kings of Africa like Ndaté Yalla Mbodj, who defied French colonizers, or Yaa Asantewaa, who rallied against British rule.

Power Through Politics and Prosperity

The Kandakes’ authority extended beyond the battlefield, blending military might with political acumen and cultural patronage. Amanishakheto, another prominent Kandake who ruled in the late 1st century BCE to early 1st century CE, exemplified this multifaceted power. While she married nobles to strengthen alliances, her reign remained hers alone—her husbands served as consorts, not co-rulers. Her independence mirrors that of Ranavalona I of Madagascar, who dominated her son’s pro-European leanings, or Queen Idia of Benin, who shaped her son’s throne.

Amanishakheto’s era was one of prosperity, reflected in the opulent pyramids and temples she commissioned at Meroë. These structures, smaller but steeper than their Egyptian counterparts, housed her tomb and treasures—gold jewelry, intricate weaponry, and artifacts unearthed by archaeologists in the 19th and 20th centuries. These finds reveal Kush’s wealth and sophistication, a testament to the Kandakes’ role as cultural patrons. Like Hatshepsut of Egypt, who built her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, Amanishakheto’s monuments blended power with artistry, leaving a legacy in stone and gold.

The Kandakes’ co-rulership with their heirs, as seen with Amanirenas and Akinidad, was a hallmark of Kushite governance—a system where maternal authority reinforced dynastic stability. This parallels Nzinga’s partnership with her sister in Ndongo and Matamba or Idia’s alliance with her son Esigie in Benin. Through war, diplomacy, and prosperity, the Kandakes forged a mighty kingdom that stood as a beacon of African sovereignty.

A Lasting Mark on History

The Kandakes’ reigns, spanning centuries, left an indelible mark on Kush and the broader narrative of African women rulers. Amanirenas’ treaty with Rome ensured Kush’s independence until the kingdom’s decline in the 4th century CE, a feat that underscores her strategic brilliance. Amanishakheto’s treasures, meanwhile, speak to a civilization that rivaled its neighbors in wealth and culture, challenging Eurocentric views of ancient Africa as peripheral.

Their stories align with those of other female kings of Africa—Mmanthatisi, who led the Tlokwa through chaos, or Hangbe, who armed the Dahomey Amazons. The Kandakes’ blend of military might and cultural patronage reflects a leadership style that defied gender norms, proving that women could rule as sovereigns with the same authority as men. In Sudan today, their pyramids at Meroë stand as silent sentinels, a reminder of a time when warrior queens held sway over a mighty kingdom.

The Kandakes of Kush join a constellation of female kings of Africa whose reigns reshaped their worlds with vision and valor. From Amina’s fortified cities in Hausaland to Ranavalona’s isolationist defiance in Madagascar, these women wielded power with ingenuity and resolve. The Kandakes’ co-rulerships, like those of Nzinga or Idia, highlight sophisticated systems where capability, not gender, defined leadership—a tradition that echoes through African history.

As modern archaeology and scholarship reclaim their legacies, the Kandakes challenge us to rethink power and sovereignty. Amanirenas’ one-eyed defiance and Amanishakheto’s golden treasures are more than relics; they are symbols of a time when African women rulers stood toe-to-toe with empires, their might etched in both battlefields and monuments. In the broader tapestry of female leadership, the Kandakes of Kush shine as sovereigns of a mighty kingdom, their reigns a testament to the enduring strength of those who ruled not as shadows, but as kings in their own right.

8. Ranavalona I of Madagascar: The Fierce Isolationist Monarch

In the annals of female kings of Africa, Ranavalona I of Madagascar stands as a formidable and polarizing figure—a warrior queen whose iron will preserve her island’s sovereignty against European domination. Ascending the Merina throne in 1828 after the death of her husband, King Radama I, she ruled with a singular mission: to protect Malagasy identity from the encroaching tides of French and British influence. Her reign, marked by isolationist policies and ruthless enforcement, delayed colonization for decades, cementing her legacy as one of the most resolute African women rulers. Though her methods earned her a reputation for tyranny, Ranavalona’s fierce nationalism aligns her with the lineage of female leaders who defied external threats to safeguard their people.

Protecting Malagasy Identity

Ranavalona I came to power in a Madagascar poised on the brink of transformation. Her husband, Radama I, had opened the island to European influence, welcoming missionaries and adopting Western innovations. But his death in 1828—some whisper by Ranavalona’s hand—ushered in a dramatic reversal. At 49, she seized the throne, determined to expel foreign encroachment and restore traditional Malagasy culture. Declaring herself queen, she expelled Christian missionaries, banned the religion they preached, and severed ties with European powers, enforcing a strict isolationist policy that closed Madagascar’s doors to the outside world.

Her measures were unrelenting. She reinstated traditional rituals, purged pro-European factions, and imposed harsh punishments—executions, forced labour, and trials by ordeal—for those who defied her edicts. These actions delayed French and British colonization, preserving Madagascar’s independence until after her death. Ranavalona’s resolve mirrors the defiance of female kings of Africa like Ndaté Yalla Mbodj, who barred trade with the French in Senegal, or Yaa Asantewaa, who rallied the Ashanti against British rule. Her reign, though brutal, was a calculated stand to protect Malagasy identity, making her a warrior queen whose legacy is as complex as it is enduring.

A Tense Co-Rulership

Ranavalona’s rule was not without internal strife, particularly in her tense co-rulership with her son, Radama II. Initially, she governed as regent for the young prince, but as he matured, their visions for Madagascar diverged sharply. Radama II favoured reopening the island to European influence, embracing Christianity and modernization—policies that clashed with his mother’s fierce isolationism. This rift turned their relationship into a battleground, with Ranavalona retaining the upper hand through her entrenched authority and loyal supporters.

The tension reached a breaking point in 1863, two years after Ranavalona’s death in 1861, when Radama II was assassinated under mysterious circumstances. Some historians speculate that Ranavalona’s allies, or even her lingering influence, played a role in his demise, though evidence remains inconclusive. This controversy adds a layer of intrigue to her reign, painting her as both a protector and a tyrant. Her co-rulership echoes the dynamics of African women rulers like Queen Idia of Benin, who shaped her son’s reign, or Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba, whose partnership with her sister bolstered resistance. Yet Ranavalona’s dominance in this arrangement underscores her singular control, a testament to her unyielding grip on power.

A Polarizing Legacy

Ranavalona I’s reign, ending with her death in 1861 at age 82, remains a polarizing chapter in Madagascar’s history. To her detractors—particularly European chroniclers—she was a cruel despot, her harsh policies claiming countless lives and stifling progress. Estimates suggest that her purges and labour demands reduced the Merina population significantly, a cost that colours her legacy with tragedy. Yet to her defenders, she was a nationalist heroine who shielded Madagascar from colonial subjugation, preserving its cultural and political autonomy for over three decades until French forces annexed the island in 1896.

Her story fits seamlessly into the narrative of female kings of Africa, women who wielded power with ferocity and foresight. Like Mmanthatisi of the Tlokwa, who led her people through chaos, or Hangbe of Dahomey, who armed the Amazons, Ranavalona’s leadership was defined by action—however harsh—to protect her realm. Her isolationism, while extreme, parallels Nzinga’s strategic defiance of Portuguese ambitions, both queens using their authority to defy foreign domination. In Madagascar, Ranavalona remains a symbol of resistance, her reign a blend of tyranny and triumph that continues to spark debate.

Her legacy challenges us to reconsider the nature of power and resistance. Ranavalona I was not a gentle ruler, but she was a warrior queen who stood firm when her people’s identity hung in the balance. As Madagascar reckons with its colonial past, her name evokes both pride and unease—a reminder that sovereignty often comes at a steep price. In the broader tapestry of African women rulers, she is a testament to the strength of those who chose defiance over submission, their reigns a call to honour the complex, courageous women who shaped Africa’s history. Ranavalona’s story, polarizing yet profound, proves that true leadership is forged in the crucible of conviction, leaving an imprint that time cannot erase.

9. Yaa Asantewaa: The Ashanti Queen Who Sparked Rebellion

In the pantheon of African women rulers, Yaa Asantewaa of the Ashanti Empire stands as a towering figure—a warrior queen whose leadership galvanized her people against British colonial oppression. Though not a king in title, her command during the War of the Golden Stool in 1900 in modern-day Ghana was as transformative as any monarch’s reign. When Ashanti men hesitated in the face of British demands, Yaa Asantewaa’s rallying cry—“If you men will not fight, we women will!”—ignited a rebellion that shook the foundations of colonial rule. Her story, etched in defiance and courage, aligns her with the legacy of female kings of Africa, proving that power lies not in a crown, but in the will to lead.

Rallying Against British Rule

Yaa Asantewaa’s rise to prominence came at a critical juncture for the Ashanti Empire. By 1900, the British had already exiled the Asantehene (king), Prempeh I, and sought to cement their dominance by demanding the Golden Stool—the sacred symbol of Ashanti sovereignty and spiritual unity. As the Queen Mother of Ejisu, a key Ashanti state, Yaa Asantewaa watched with growing alarm as Ashanti leaders wavered, reluctant to confront the colonial power. At a pivotal meeting, she seized the moment, delivering her now-iconic speech that shamed the men into action and positioned her as the rebellion’s heart and soul.

Taking up arms at the age of 60, Yaa Asantewaa led the War of the Golden Stool, also known as the Yaa Asantewaa War, with unrelenting resolve. She mobilized troops, organized defenses, and inspired warriors to protect their land and heritage. Her leadership echoed the martial spirit of female kings of Africa like Hangbe of Dahomey, who trained the Amazons, or Ndaté Yalla Mbodj of Waalo, who clashed with French forces. Though she lacked a formal throne, Yaa Asantewaa’s authority as a warrior queen was undeniable, her defiance a beacon for a people facing subjugation.

A Defiant Legacy

The War of the Golden Stool raged from March to September 1900, with Yaa Asantewaa’s forces employing guerrilla tactics against the better-armed British. She fortified stockades, directed ambushes, and sustained the Ashanti spirit even as the odds mounted. Ultimately, the rebellion was crushed—British firepower and reinforcements proved too formidable. Yaa Asantewaa was captured and exiled to the Seychelles, where she died in 1921. The Golden Stool, though hidden by the Ashanti, fell under British influence, marking a bitter end to the conflict.

Yet her defeat was not the end of her story. Yaa Asantewaa’s stand delayed British consolidation of power in the Gold Coast, forcing them to expend resources and time to subdue the Ashanti. More importantly, her rebellion sowed seeds of resistance that inspired future generations, contributing to Ghana’s eventual independence in 1957. Today, she is revered as a Ghanaian heroine, her name synonymous with courage and sacrifice. Schools, festivals, and monuments—like the Yaa Asantewaa Museum in Ejisu—bear her legacy, ensuring that her voice continues to echo through time.

Her defiance aligns her with African women rulers like Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba, whose anti-colonial treaties frustrated Portuguese ambitions, or Queen Idia of Benin, whose battlefield triumphs secured her son’s reign. Yaa Asantewaa’s leadership, though not crowned, embodied the essence of a female king of Africa—a ruler who wielded power through action and inspiration, not just title.

As Ghana and the world honour her legacy, Yaa Asantewaa stands as a symbol of resistance against oppression—a warrior queen whose courage reverberates beyond her time. Her rebellion challenges us to rethink leadership, not as a privilege of rank, but as a force born of necessity and conviction. In the broader narrative of African women rulers, she is a testament to the enduring truth that power is claimed, not bestowed—forged in the fire of struggle and carried forward by those who refuse to yield. Today, her spirit inspires not just Ghanaians, but all who seek to reclaim history’s unsung heroes, proving that even in defeat, a queen can light the path to freedom.

10. Hangbe of Dahomey: The Warrior Queen Who Forged an Army

11. Ndaté Yalla Mbodj: The Last Queen of Waalo Who Fought Colonialism

12. Queen Idia of Benin: The Iyoba Who Shaped a Dynasty

In the annals of the Benin Kingdom, few figures loom as large as Queen Idia, a woman whose influence transformed her from a royal mother into a kingmaker and a female king of Africa. Rising to prominence around 1504 in what is now modern Nigeria, Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie, wielded power with a rare blend of military might, spiritual authority, and cultural patronage. After the death of her husband, Oba Ozolua, she navigated a treacherous succession war to secure her son’s throne, earning the title Iyoba—queen mother—and establishing it as a permanent institution of king-like authority. Idia’s story is a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of African women rulers, her legacy echoing through the centuries in the form of her iconic ivory mask and the enduring strength of Benin’s monarchy.

From Queen Mother to Kingmaker

Queen Idia’s ascent began in the wake of Oba Ozolua’s death, when the Benin Kingdom faced a crisis of succession. Two brothers—Esigie and Arhuaran—vied for the throne, threatening to fracture the empire. Idia, fiercely loyal to her son Esigie, emerged as a decisive force in this power struggle. Far from a passive figure, she orchestrated his victory, leveraging her influence and resources to ensure his coronation around 1504. Her triumph marked a turning point, not just for Esigie’s reign, but for the role of women in Benin’s governance.

In recognition of her pivotal role, Esigie bestowed upon her the title of Iyoba, or queen mother—a position that Idia imbued with unprecedented authority. Unlike a ceremonial honour, the Iyoba became a formalized office, granting her a palace, a council, and powers akin to those of a king. This elevation mirrors the trajectories of other female kings of Africa, such as Mmanthatisi of the Tlokwa, who ruled as regent-turned-king, or Hatshepsut of Egypt, who declared herself pharaoh. Idia’s transformation from queen mother to kingmaker cemented her as a ruler in her own right, defying gender constraints in a patriarchal system.

Warrior and Cultural Patron

Idia’s legacy is not confined to political manoeuvring; she was also a warrior queen whose leadership on the battlefield secured Benin’s stability. During Esigie’s reign, she led armies into combat, reportedly wielding spiritual powers that struck fear into her enemies and bolstered her troops. This mystical aura recalls the Rain Queens of the Lovedu, whose reputed control over natural forces enhanced their authority. Idia’s victories—particularly against external threats and rebellious factions—ensured the kingdom’s survival during a period of regional turmoil, solidifying her reputation as a formidable leader.

Beyond the battlefield, Idia’s influence extended to Benin’s cultural flourishing. As a patron of the arts, she fostered an artistic golden age that produced the kingdom’s renowned Benin bronzes, including the famous ivory mask that immortalizes her likeness. Crafted with exquisite detail, this mask—featuring her serene yet commanding face framed by coral beads—symbolizes her dual role as warrior and nurturer. It gained international prominence as the emblem of FESTAC ’77, the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture, held in Nigeria in 1977. Through her patronage, Idia not only defended Benin’s borders but enriched its soul, leaving a cultural legacy that endures to this day.

Fit in Benin’s Legacy

Idia’s de facto rulership places her firmly among the female kings of Africa, a lineage of women who shaped empires through strategy, sacrifice, and defiance. Her co-rulership with Esigie parallels Nzinga’s partnership with her sister Kifunji in Ndongo and Matamba, where power-sharing amplified their impact against colonial foes. Similarly, the Kandakes of Kush ruled alongside their heirs, blending maternal and martial authority. In Benin, Idia’s establishment of the Iyoba as a permanent office ensured that future queen mothers would wield influence, a structural innovation that reflects the sophistication of African governance systems.

Her story dismantles stereotypes of African women as secondary figures, revealing instead a leader whose military prowess and cultural vision rivaled those of her male counterparts. Like Amina of Zazzau, who fortified cities, or Mmanthatisi, who led migrations, Idia’s reign exemplifies how African women rulers transcended traditional roles to leave indelible marks on their societies. Her legacy in Benin is one of empowerment—a reminder that leadership thrives on capability, not gender.

Queen Idia’s Legacy: The Mask in Exile

Idia’s enduring symbol, the ivory mask, carries her story far beyond Benin’s borders—yet it also embodies a poignant tale of exile. One of the most famous iterations of this mask, looted by British forces during the punitive expedition of 1897, resides in the British Museum, a relic of colonial plunder. This displacement mirrors the fate of other iconic representations of African female leaders, such as the Ngonnso statue of the Nso people in Cameroon. Crafted to honour a revered female founder, the Ngonnso has languished in a German museum for over a century, taken during colonial rule in the early 20th century. Both artifacts—Idia’s mask and the Ngonnso—stand as testaments to the power of female kings of Africa, yet their exile underscores the broader loss of cultural heritage to foreign hands. As movements for repatriation gain momentum, these objects remain potent symbols of resilience, their absence a call to reclaim the legacies of Africa’s warrior queens and visionary rulers. In their stories, and in the fight to bring them home, we find a timeless challenge: to honour the past by restoring what was taken, ensuring that Idia and her peers are fully recognized as architects of history.

13. Mmanthatisi of the Tlokwa: The Regent Who Led Through Chaos

In the turbulent early 19th century, as Southern Africa reeled from the upheaval of the Mfecane, one leader emerged as a towering figure of resilience and strength: Mmanthatisi of the Tlokwa. Ruling the Tlokwa people in what is now South Africa’s Free State, Mmanthatisi navigated her nation through a period of war, migration, and survival, earning her place among the female kings of Africa. As regent for her young son Sekonyela following her husband’s death, she transcended the role of caretaker to become a de facto king—a warrior queen whose leadership during crisis parallels the legacies of other African women rulers like Orompoto of Oyo and Hangbe of Dahomey. Her story is one of military prowess, strategic brilliance, and enduring influence, offering a powerful testament to the capability of women in shaping history.

Leadership During the Mfecane: A Ruler Forged in Chaos

The Mfecane, spanning roughly from 1815 to the 1830s, was a time of seismic disruption in Southern Africa, driven by the expansion of the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka and the resulting domino effect of migrations and conflicts. Amid this chaos, Mmanthatisi rose to prominence among the Tlokwa, a Sotho-Tswana group. Her husband, Chief Mokotjo, died around 1815, leaving her to govern as regent for their son, Sekonyela, who was too young to rule. What might have been a temporary stewardship evolved into a reign of commanding authority, as Mmanthatisi took the reins during one of the most perilous eras in her people’s history.

Rather than merely holding the line, Mmanthatisi transformed the Tlokwa into a mobile, formidable force. She led her people through a landscape fractured by rival factions, displaced communities, and scarce resources, asserting her leadership in a way that defied the gender norms of her time. Like Hatshepsut of Egypt centuries earlier, who declared herself pharaoh, or Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba, who negotiated power amidst colonial pressures, Mmanthatisi’s rule exemplifies the archetype of female kings of Africa—rulers who stepped into power with vision and grit when circumstances demanded it.

Military Prowess in a Time of Crisis

Mmanthatisi’s reign was defined by her military leadership, earning her the mantle of a warrior queen. As the Mfecane uprooted communities and intensified competition for land and cattle, she guided the Tlokwa on a campaign of survival and conquest. Her forces raided neighboring settlements, securing cattle, grain, and other resources essential to her people’s endurance. These expeditions were not mere acts of aggression but calculated moves to ensure the Tlokwa’s stability in a world turned upside down.

Her strategic mobility—moving her people across vast distances to evade stronger enemies and exploit weaker ones—mirrored the tactics of other African women rulers. Orompoto of the Oyo Empire, a 16th-century Yoruba leader, used cavalry to expand her domain, while Hangbe of Dahomey led her kingdom’s famed female warriors in battle. Mmanthatisi’s reputation grew fearsome, with colonial and missionary accounts exaggerating her as a “cannibal queen” or a giantess who devoured her foes. These distortions, born of fear and misunderstanding, obscured her true strength: a leader who wielded power with resilience and adaptability, not savagery.

Unlike the monumental builders like Hatshepsut, who left temples as their legacy, or the fortified city-makers like Amina of Zazzau, Mmanthatisi’s mark was etched in the survival of her people. Her leadership during the Mfecane ensured the Tlokwa emerged from the chaos intact, a feat that required not just military might but a deep understanding of her environment and adversaries.

A Lasting Influence

Mmanthatisi’s tenure as leader eventually drew to a close as Sekonyela came of age and assumed full control, likely in the late 1820s or early 1830s. She stepped back from power, fading into the background of Tlokwa history, her later years shrouded in obscurity. Yet her impact endured. The Tlokwa, under her guidance, weathered the Mfecane’s storms, a testament to her ability to unite and protect her people during an era of unrelenting hardship.

Her legacy resonates as a symbol of female authority in Southern Africa, aligning her with the broader narrative of female kings of Africa. While she lacked the diplomatic treaties of Nzinga or the spiritual stewardship of Benin’s Omu, Mmanthatisi’s reign embodied the raw, unyielding strength of a warrior queen. Her story challenges stereotypes of African women as passive figures in history, revealing instead a leader who shaped her people’s destiny through courage and decisive action.

14. Hatshepsut of Egypt: The only Female Pharaoh Who Ruled as King

In the annals of ancient history, few figures stand as tall—or as enigmatic—as Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s most iconic pharaohs. Ruling from 1478 to 1458 BCE during the 18th Dynasty, Hatshepsut’s ascension to power defied convention, her reign reshaped Egypt’s fortunes, and her legacy, though once erased, now shines as a beacon of female leadership. Often overshadowed by Egypt’s male warrior-kings in popular narratives, Hatshepsut’s story reveals her as an archetype of the female kings of Africa—a ruler whose ingenuity, authority, and vision prefigured the likes of Amina of Zazzau, Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba, and other African women rulers who would follow centuries later. Her reign challenges us to reconsider not just Egypt’s history, but the broader tapestry of leadership across the continent.

Ascension in Ancient Egypt: From Regent to King

Hatshepsut’s rise to power was as audacious as it was unprecedented. Born into royalty as the daughter of Thutmose I, she married her half-brother, Thutmose II, securing her place in the royal lineage. When Thutmose II died, leaving behind a young heir—Thutmose III, Hatshepsut’s stepson—she was appointed regent, a role typically reserved for queens overseeing a child king. But Hatshepsut was no mere placeholder. In a bold move, she declared herself pharaoh, adopting a king’s full regalia and titles, including “King of Upper and Lower Egypt” and “Son of Ra.” In official art, she donned a false beard and kilt, symbols of male kingship, effectively blurring gender lines in a society where such roles were rigidly defined.

This gender-defying ascension resonates with later female kings of Africa, like Amina of Zazzau, who ruled as a warrior queen in 16th-century Nigeria, or Nzinga, who negotiated power with European colonizers in 17th-century Angola. While ancient Egypt predates these pre-colonial African kingdoms, Hatshepsut’s story mirrors their defiance of patriarchal norms, establishing her as an early exemplar of African women rulers who wielded power with unapologetic authority.

Peaceful Prosperity and Monumental Legacy

Unlike the warrior queens who dominate tales of African female leadership—figures like the Kandakes of Kush, who led armies against Roman invaders—Hatshepsut’s reign was defined by peace, prosperity, and monumental ambition. She eschewed military conquest for economic expansion, most famously through her trade expedition to the land of Punt, believed to be located in modern-day Somalia or Eritrea. This voyage brought back treasures like myrrh, frankincense, gold, and exotic animals, enriching Egypt’s coffers and cementing its status as a regional powerhouse. The wealth from these ventures fueled Hatshepsut’s ambitious building projects, including her stunning mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, a marvel of architecture carved into the cliffs near the Valley of the Kings.

Her temple, with its terraced design and colonnades, stands as a testament to her vision—a legacy in stone that rivals the pyramids. Inscriptions there depict her divine birth, claiming legitimacy as a ruler chosen by the god Amun, a narrative that reinforced her kingly status. This focus on trade and construction rather than warfare sets Hatshepsut apart from the warrior queen archetype, yet her authority was no less commanding. She ruled as a king, not a queen, proving that power could be wielded through diplomacy and innovation as effectively as through the sword.

Erasure and Rediscovery

Hatshepsut’s death around 1458 BCE marked the beginning of a deliberate campaign to erase her from history. Her stepson, Thutmose III, who ascended to full power after her demise, ordered her name chiseled off monuments and her statues smashed. Whether motivated by personal resentment or political strategy, this erasure nearly succeeded in burying her legacy. For centuries, her story languished in obscurity, a forgotten chapter in Egypt’s grand narrative.

Yet the 19th and 20th centuries brought her back to light. Modern archaeology restored Hatshepsut’s place in history through excavations at Deir el-Bahri and the deciphering of fragmented records. Today, she is celebrated as one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs—a ruler whose reign challenges the stereotype of African women rulers as mere consorts or secondary figures. Her rediscovery aligns her with later female kings of Africa, whose legacies were similarly reclaimed from the margins of history, revealing the depth and diversity of female leadership across the continent.

The Enduring Impact of Africa’s Female Kings

From Amina’s fortified cities to Nzinga’s anti-colonial treaties and the Omu’s spiritual stewardship, these women wielded power with ingenuity and grit. Co-rulerships—like Nzinga’s with her sister, the Kandakes’ with their heirs, or the Omu’s alongside the Obi—highlight sophisticated systems where capability trumped gender. Their stories dismantle stereotypes of African women as passive, revealing instead leaders who shaped empires through war, diplomacy, and defiance.As modern movements reclaim these legacies, these female kings offer timeless lessons: power isn’t bound by gender, but by vision, strategy, and courage. Their reigns challenge us to rethink history—and leadership itself.