We Are Not Africans

Imagine waking up one morning, blinking into the dim light of a world that feels faintly off—like you’re a character in a video game coded by someone who didn’t bother to ask your name. Your avatar’s tag floats above your head in glitchy, neon letters: “African.” It’s not a badge of honor; it’s a branding error, a pixelated label flickering over a continent of peoples who never logged in to this server. You didn’t choose it, didn’t design it, didn’t even get a say in the tutorial. Yet here you are, stuck in a simulation where the rules, the storyline, and even your own reflection feel scripted by a developer who doesn’t know your real story—or worse, doesn’t care to.

That’s “African” in a nutshell—a name so vague, so hollow, it’s less an identity than a loading screen for a game we didn’t sign up to play. It’s not a homeland humming with the voices of our ancestors; it’s a social engineering masterpiece, a carefully stitched costume that drapes us in ideologies, mentalities, and characters as alien as the creaking wooden ships that first scraped onto our shores centuries ago. Those ships didn’t just bring guns and trinkets—they brought a blueprint, a colonial algorithm designed to overwrite who we were with who they needed us to be. And “African”? That’s the username they assigned us, a catch-all to log us into their system, stripping away the infinite diversity of our nations, tongues, and histories for a one-size-fits-all profile pic.

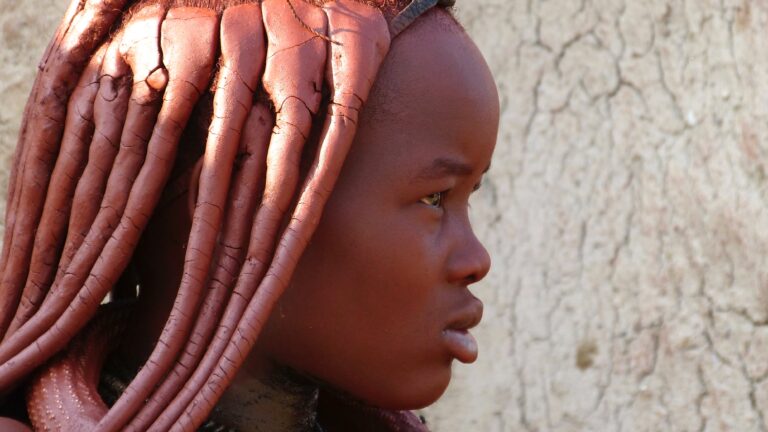

Let’s be real: calling us “Africans” is like calling a library a single book—it’s lazy, it’s reductive, and it’s a lie. Before the maps were redrawn and the treaties signed, we weren’t a monolith. We were the Ashanti forging empires in gold, the Zulu hurling spears against invaders, the Hausa trading wisdom across the Sahel, the Yoruba weaving philosophies into oriki chants. We were kingdoms and clans, nomads and farmers, priests and poets—each with names we gave ourselves, rooted in soil we knew as ours. Then came the glitch: a word, “Africa,” whispered first by Romans sniffing around Carthage, later hijacked by men in powdered wigs who saw a continent not as a living tapestry but as a treasure chest to crack open. That word wasn’t ours—it was theirs, a colonial Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V to paste over our realities.

This isn’t just semantics; it’s a heist of the soul. To be “African” in their simulation is to inherit a character preset—poor, primitive, perpetually in need of saving—while the game’s developers rake in the profits. It’s a mental jailbreak, convincing us our past begins where their story does, that our worth is tied to their markets, their gods, their borders. Look at the evidence: in this sprawling tale, we’ll unravel how “Africa” was turned into a commodity during the Scramble for Africa, a historical smash-and-grab that left us with a barcode instead of a birthright. We’ll dig into how our kings—fierce, flawed, but ours—were swapped for puppets on colonial strings, leaving us with traditional institutions that creak like rusted machines.

And it doesn’t stop there. Our spiritual roots were uprooted and replaced with Christianity’s Trojan horse, a faith that preached peace while pocketing our artifacts and our people. Our languages—vessels of our genius—were colonized too, ancient scripts like Nsibidi swapped for Latin letters in a linguistic coup that still echoes in doomsday predictions about our tongues going extinct. Our governments? Once led by warrior kings, they’re now staffed by thieves brokering deals with the same empires that drew the lines we live within. This is the simulation: a world where every piece of us—our names, our rulers, our beliefs, our words—was hijacked to keep us playing someone else’s game.

So buckle up. This isn’t just a story—it’s a jailbreak manual. We’re peeling back the code, line by line, to see how “African” became the ultimate con. It’s not about nostalgia for some lost Eden; it’s about recognizing the glitch for what it is and asking: if we’re not Africans—not in their sense—then who are we? Spoiler: the answer’s older, deeper, and a hell of a lot more dangerous than their servers can handle. Let’s dive in.

II. The Fiction of Africa: A Commodity, Not a Continent

Picture this: it’s November 1884, and a gaggle of pale men in stiff collars and powdered wigs huddle around a polished table in Berlin. The air’s thick with cigar smoke and arrogance as they unroll a map of a continent they’ve barely set foot on. With the precision of a butcher carving up a Thanksgiving pie, they start slicing—red lines here, blue lines there, a dash of green for good measure. This wasn’t a geography lesson; it was the Scramble for Africa, a historical heist so audacious it makes modern-day corporate takeovers look like kids trading marbles. But here’s the kicker: it wasn’t just a land grab. It was a branding campaign—a full-on rebrand of an entire continent, complete with a snappy new logo: “Africa.”

These men—Bismarck, Leopold, a roster of European royals and profiteers—didn’t see kingdoms or cultures when they stared at that map. They didn’t see the Songhai’s sprawling trade networks, the Mali Empire’s golden libraries, or the Kongo’s intricate bronze works. They didn’t see people with histories stretching back millennia, with names and gods and songs of their own. Nah, they saw a loot box—a glittering, unopened chest in their colonial video game, ripe to be plundered, renamed, and sold off to the highest bidder. The Berlin Conference wasn’t about discovery; it was about packaging. They took a tapestry of nations—hundreds of languages, thousands of clans, countless ways of being—and shrink-wrapped it into a single, digestible stereotype. “Africa,” they called it, a word dusted off from Roman scraps and repurposed as a catch-all tag to blur the edges of who we were into something they could market.

Let’s not kid ourselves: “Africa” isn’t a place—not in any real, living sense. It’s a product, a colonial SKU slapped on the shelf of empire. Before 1884, there was no “Africa” as we know it. There was Igboland, where yam festivals pulsed with communal pride; there was Dahomey, where amazons wielded machetes against invaders; there was Ethiopia, defying the script with emperors who traced their line to Solomon. These weren’t dots on a blank slate—they were worlds, sovereign and distinct. But the Berlin boys didn’t care about that. They saw rubber in the Congo, gold in the Transvaal, ivory in the East, and a whole lot of bodies to work the mines and plantations. So they drew their lines—arbitrary, jagged, cutting through ethnic groups like a drunk tailor with scissors—and declared it a continent. Their continent. And with those lines came the real magic trick: convincing us it was ours too.

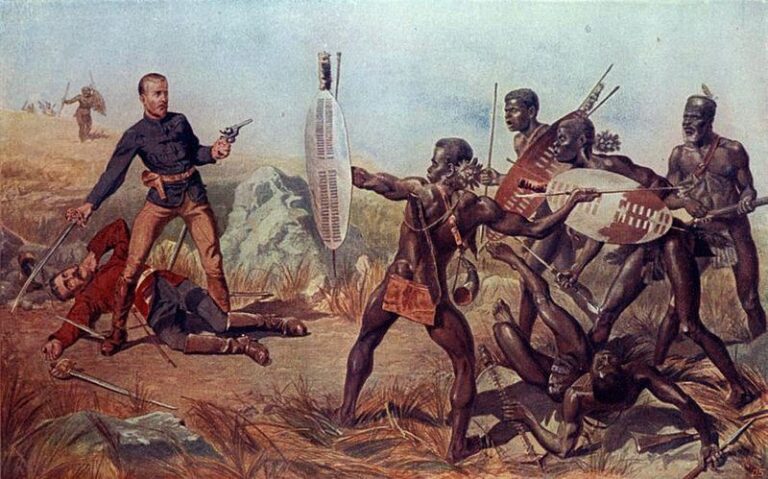

This was social engineering at its slickest, a masterclass in psychological hijacking. Step one: erase the past. Tell the Ashanti their gold was just shiny dirt until the British weighed it. Tell the Zulu their spears were quaint until the Maxim gun showed up. Tell the Hausa their trade routes were backwaters until the steamship arrived. Step two: sell the new script. “You’re Africans now,” they said, as if a single word could bottle up the chaos of conquest and call it unity. It’s like telling a lion, an elephant, and a gazelle they’re all just “animals”—true in the vaguest sense, but useless when the cage door slams shut. The label wasn’t meant to empower us; it was meant to erase us, to sand down our edges until we fit their narrative of savagery needing salvation, of resources needing owners.

And oh, how they cashed in. The Congo Free State—Leopold’s private playground—bled rubber and lives, with millions hacked apart for profit while he played philanthropist in Brussels. The Gold Coast churned out cocoa and bullion, its chiefs reduced to middlemen for British firms. Nigeria’s palm oil greased the wheels of the Industrial Revolution, while its people got beads and Bibles in return. This wasn’t trade; it was theft, masked as progress. “Africa” became a commodity, a brand synonymous with exploitation—raw materials out, finished goods in, and a people left to live the script written in Berlin. A script that said our past didn’t matter, our diversity was a glitch, and our future belonged to them.

But the real genius? They didn’t just sell it to their own people—they sold it to us. Generations later, we’re still reciting their lines, calling ourselves “Africans” like it’s a birthright instead of a barcode. That’s the con: convince a people their history starts where you say it does, and they’ll march to your drumbeat. Want proof? Look at the fall of our kings — warriors like Kabaka Mwanga II and Jaja of Opobo, toppled to make way for puppets who’d sign the dotted line. Or peek at the governments we inherited, built to protect British interests, not ours. The Scramble didn’t end in 1884—it’s still playing out, every time we buy the fiction that “Africa” is who we are. Spoiler: it’s not. It’s what they made us, and it’s time we stopped shopping their store.

III. The Fall of Kings: Puppets Over Warriors

Before the starched suits and ink-stained treaties, we had rulers who weren’t afraid to bleed for their people—kings and chiefs forged in fire, not paper. These weren’t men who bowed to strangers with funny hats and muskets; they were warriors, strategists, guardians of a world that hummed with its own rhythm. They stood tall against the tide of colonial greed, their names echoing defiance across the savannahs, forests, and coasts. But one by one, the empires of Europe—British, French, Portuguese, German—came with their guns, their lies, and their maps, toppling these titans to clear the way for their own game. In their place? Puppets—hollowed-out shells of royalty, propped up like mannequins to parrot the empire’s lines. What we’re left with today—those creaking, corrupt “traditional institutions”—are nothing but their ghosts, haunting a land that’s been conquered and convinced it’s free.

Take Kabaka Mwanga II of Buganda, a king who didn’t play nice with meddlers. Ascending the throne in 1884 at just 18, he ruled a kingdom that dazzled with its organization—roads, courts, a navy of canoes slicing Lake Victoria. But the British sniffed opportunity, their missionaries and traders worming into his court like termites. Mwanga saw the trap: Christianity wasn’t just a religion—it was a battering ram for control, splitting his people between converts and loyalists. When he resisted, executing converts who defied him and rallying against foreign influence, the British branded him a tyrant. By 1897, they’d had enough—deposed him, dragged him off his throne, and exiled him to the Seychelles, where he died a broken man. Buganda’s spirit? Crushed under a “protectorate” that cared more for cotton than culture.

Then there’s Kabalega of Bunyoro-Kitara, a lion of a king who wouldn’t roll over. In the 1870s and ‘80s, he rebuilt a kingdom battered by wars, arming his warriors with guns traded from the coast to fend off British encroachment. When the redcoats came, led by men like Samuel Baker and later Frederick Lugard, Kabalega didn’t blink—he fought. For years, he harried their columns with guerrilla tactics, a thorn in the side of an empire that wanted his oil-rich lands quiet and compliant. But in 1899, betrayed by allies and outgunned, he was captured, his legs shackled, and shipped to the Seychelles too. Bunyoro’s resistance died with his exile, its once-proud throne reduced to a footnote in Britain’s ledger.

Across the Niger Delta, Jaja of Opobo pulled off a masterclass in outfoxing the British—until they turned the tables. Born into slavery in 1821, he clawed his way to freedom and built a trading empire that rivaled Europe’s own. By the 1870s, Opobo was a powerhouse, funneling palm oil to the world while Jaja kept British merchants at arm’s length, undercutting their monopolies. The Brits didn’t like that. In 1887, they lured him onto a ship under a promise of talks, then kidnapped him mid-handshake—exiled him to the West Indies, where he died in 1891. Opobo’s independence? Snuffed out, its wealth rerouted to London’s coffers.

The list goes on. The Sultan of Zanzibar, Khalid bin Barghash, tried to hold his island’s reins in 1896, only to face the shortest war in history—38 minutes of British bombardment that left his palace rubble and his title a joke under their “protection.” The Ọbá of Benin, Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, ruled a Benin City glittering with bronze until 1897, when the British sacked it, looted its treasures, and shipped him to Calabar for daring to resist their trade demands. On the Gold Coast, chiefs like Nana Yaa Asantewaa of the Ashanti rallied against British gold lust in 1900, only to be crushed and exiled, their authority handed to yes-men who’d nod at colonial decrees. Even Egypt’s Khedive Ismail, dreaming of a modern Nile empire in the 1870s, was toppled by British debt traps, his successors mere puppets for Suez Canal profits.

These weren’t just kings—they were pillars, holding up systems that worked for us, not them. Kabaka Mwanga’s Buganda had laws and taxes; Kabalega’s Bunyoro had strategy; Jaja’s Opobo had commerce. They weren’t perfect—some were harsh, others proud to a fault—but they were ours, rooted in our soil, not imported from foggy islands across the sea. The colonial machine didn’t just dethrone them; it hollowed them out. In their place came puppets—chiefs and “traditional rulers” installed or co-opted to grease the wheels of empire. Sign this treaty, they were told. Tax your people for us. Keep them in line. And they did, their crowns turned into costumes, their power a shadow play directed from London, Paris, or Lisbon.

Today’s traditional institutions—those dusty stools, those toothless councils—are their legacy. In Nigeria, the emirs and obas who once led armies now rubber-stamp government edicts. In Uganda, the kabakas’ palaces are tourist traps, their authority a whisper. Across the continent, these ghosts of power creak along, corrupt not because we made them so, but because they were built broken—designed to serve the fiction of Africa as a commodity, not a continent of sovereigns. The British didn’t just conquer land; they conquered legitimacy, leaving us with marionettes dangling on strings that stretch back to Berlin. Want to see the fallout? Check the governments of thieves still cutting deals with the same oppressors. The kings fell, and with them, a piece of who we were—replaced by a puppet show we’re still watching.

IV. Christianity as a Trojan Horse

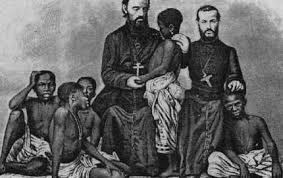

Picture the scene: a dusty village square, the air thick with the hum of daily life—women pounding yam, elders swapping tales, drums pulsing in the distance. Then, a shadow falls. Men in black robes and wide-brimmed hats stride in, Bibles clutched in one hand, the glint of chains dangling from the other. They didn’t just bring a god—they rolled in a Trojan horse, a gift wrapped in promises of eternal light but packed with the tools of conquest. These missionaries weren’t here to save souls; they were advance scouts for empire, building a parallel farce to the puppet kings already strung up by colonial hands. Their gospel split communities like an axe—converts on one side, holdouts on the other—turning brother against brother, all while the real prize was carted off under the cross. Christianity didn’t come to redeem us—it came to strip us bare.

The playbook was simple: infiltrate, divide, plunder. In Buganda, the missionaries trailed the British like vultures after a lion’s kill. By the 1880s, Kabaka Mwanga II watched his kingdom fracture—his court, once a tight-knit web of loyalty, now a battleground between Anglican and Catholic converts egged on by rival European factions. The “Martyrs of Uganda,” 45 young men burned or speared in 1886 for defying the king’s authority, weren’t just casualties of faith—they were pawns in a power play. Their deaths gave the British a moral cudgel to paint Mwanga as a savage, justifying his deposition in 1897. Religion wasn’t the endgame; it was the wedge, prying open a kingdom for colonial control.

Across the continent, the pattern repeated. In the Congo, missionaries like the White Fathers blessed Leopold’s “civilizing mission” while his agents hacked off hands for rubber quotas. In South Africa, Dutch Reformed preachers sermonized to the Khoikhoi and Xhosa in the 1700s and 1800s, softening them up for Boer land grabs—converts got heaven, settlers got the earth. In Nigeria, the Church Missionary Society shadowed the palm oil trade, planting crosses where British merchants planted flags. The message was salvation, but the method was sabotage—turn a people’s spiritual roots into kindling, then light the match. Communities that once gathered under baobabs to honor ancestors now knelt in pews, their old ways branded as devilry, their cohesion shattered.

And here’s the betrayal that stings deepest: the Church didn’t storm in with guns blazing—they were welcomed. Our people, our communities, opened their arms to these robed strangers, mistaking their soft words for sincerity. Compared to the brash traders haggling over ivory or the redcoats barking orders, the missionaries seemed gentle, almost benign. Villages offered them land—freely, generously—places to build their chapels and schools, trusting these guests bore goodwill. Fast forward, and that trust was a noose. Today, the Catholic and Anglican churches jointly hold more land across Africa than some entire nations—estimates suggest the Catholic Church alone owns over 177 million acres globally, with vast swathes in Africa, while Anglican holdings stretch across former British colonies. Add in Methodists, Presbyterians, and Pentecostals, and the acreage could carve out a subregion—think a Christian Sahel, built on gifts we gave. Yet these guests turned predators, biting the fingers that fed them. They smeared our cultures as savage, taught our children their parents were evil, and destabilized their hosts with a zeal that rivaled any army. Ancestors who guided us for centuries became demons in their sermons; our shrines, once sacred, were now “heathen.” To most Africans today, our ancestral ways aren’t worth a prayer—only a Eurocentric system, dressed in white robes and guilt, must be upheld, even if we die defending it.

The looting was shameless. Under the guise of saving us from “paganism,” missionaries and their colonial tagalongs pillaged like it was a divine right. In Benin City, after the British sacked the Ọbá’s palace in 1897, missionaries cheered as thousands of bronze plaques—masterworks of a 500-year-old tradition—were crated off to London museums [*Benin Bronzes* – British Museum](https://www.britannica.com/topic/Benin-bronze). Ethiopia’s Magdala fell in 1868 to British troops, with priests pocketing manuscripts and crosses, sacred relics now gathering dust in the British Museum. The Congo’s Kuba textiles, Ashanti gold weights, Zulu beadwork—entire libraries of knowledge carved in wood, woven in cloth, etched in metal—vanished into European vaults, labeled “curiosities” while we were left with hymns and empty shrines.

The theft wasn’t just stuff—it was us. In the slave trade’s heyday, from the 1500s to the 1800s, missionaries baptized captives before they were chained into ships—Portugal’s Jesuits alone oversaw millions shipped from Angola, their souls “saved” as their bodies were sold. The Bible didn’t stop the whips; it blessed the hulls. Fast forward to now, and the chains are subtler—visas, scholarships, “better lives” dangled like carrots to lure away the best of us. Doctors, engineers, thinkers—our brightest minds drain to London, Paris, New York, building their cities while ours crumble. Immigration’s just slavery with extra steps, and Christianity’s still the bait, promising a seat at the table while we’re stuck washing the dishes.

This wasn’t salvation—it was a heist with a halo. The missionaries didn’t lift us up; they hollowed us out, mirroring the puppet kings with a clergy just as compliant. Their churches stood as outposts of empire, their sermons a lullaby to keep us docile while our heritage was smuggled out the back door. Look at the language trap — Latin letters came with their catechisms, burying scripts like Nsibidi to cut us off from our own stories. Or peek at the governments of thieves —mission schools churned out clerks and lackeys to staff colonial bureaucracies, not leaders to free us. Christianity didn’t save us—it was the soundtrack to our stripping, a hymn hummed over a continent picked clean.

V. The Language Trap: Colonizing the Tongue

Our words were once more than sounds—they were living threads, weaving us to our past, our land, our selves. Across the forests of the Igbo and Efik, Nsibidi danced on bark and skin—symbols sharp as a leopard’s claw, ancient as the rivers, alive with meaning only we could unlock. In Ethiopia, Ge’ez script glittered on parchment, a sacred alphabet tying kings to Solomon’s line. The Akan scratched wisdom into gold weights; the Bamum of Cameroon crafted their own syllabary under King Njoya in the 1890s, a defiant burst of ink against oblivion. These weren’t just letters—they were ours, vessels of memory and power, etched by hands that knew their worth. Then came the colonial overwrite: Latin letters, a cold, foreign grid dropped like a net over our tongues, severing us from those roots as cleanly as an axe through a sapling.

Nsibidi’s a museum piece now, a curiosity gawked at by tourists in places like the [National Museum of Nigeria](https://www.museum.ng), useless in a world that demands English, French, or Portuguese to buy a loaf of bread or sign a lease. Ge’ez survives in church chants, but Amharic bends under Roman type. Bamum script? Smothered by French rule, its inventor exiled, its legacy a footnote. The missionaries brought their Bibles, the traders their ledgers, the governors their laws—all in alphabets we didn’t birth. They didn’t just teach us to write their way—they convinced us our ways were dead ends, primitive scratches unfit for a “modern” world. It was a linguistic coup, a slow strangling of our voices until we parroted theirs, our own scripts left to rot like abandoned shrines.

And they didn’t stop at rewriting—they prophesied our erasure. Linguists with Western grants—UNESCO, SIL International—warn that African languages are dying, ticking off names like Swahili’s cousins or the clicks of Khoisan as if they’re endangered species. By 2100, they say, half our tongues could be gone—3,000 languages snuffed out, a cultural genocide framed as inevitable. It’s a scare tactic, a megaphone blaring: “Your ship’s sinking—jump aboard our lifeboats!” English, French, Spanish—those are the cruise liners, shiny and sanctioned, promising jobs, prestige, a ticket to the global party. Meanwhile, Yoruba’s proverbs, Hausa’s poetry, Zulu’s idioms—they’re cast as relics, too heavy to carry into the future. It’s globalization’s mind game, a psychological shove to abandon our “backward” dialects for their polished lexicon, as if our words are baggage and theirs are gold.

This wasn’t an accident—it was a trap, sprung with precision. In Nigeria, colonial schools banned Igbo and Hausa, flogging kids who dared whisper their mother tongues—by 1900, English was the ladder, and our languages the dirt beneath it. In Senegal, Wolof bowed to French, its griots sidelined for Parisian textbooks. Across East Africa, Swahili held on, but only as a pidgin for trade, its depth diluted under British thumbs. The missionaries were the vanguard—Latin letters came with their catechisms, turning oral traditions into footnotes while they preached salvation through spelling. The result? A continent of polyglots who can’t read their own history, who stumble over Nsibidi or Tifinagh like it’s a foreign code, because it’s been made foreign to us.

The damage echoes. Our languages aren’t just words—they’re worldviews, carrying cosmologies, laws, identities. Lose them, and we lose the map to who we were before the ships came. Western-backed “end times” predictions aren’t prophecy—they’re policy, engineering our minds to ditch the sinking ship for their fleet. Look at the governments of Africa —they sign deals in English, French, languages of the oppressors, not ours. The trap’s still snapping shut: every kid taught to dream in a colonizer’s tongue is another root pulled up, another link to the past snapped. We’re not sinking—we’re being scuttled, and they’re selling us the lifeboats.

VI. Governments of Thieves, Not Kings

We were once led by warrior kings—fierce as the harmattan wind, accountable to the people who crowned them, ours in blood and bone. Men like Sundiata Keita, who forged Mali’s golden age with a sword and a promise, or Shaka Zulu, whose spear carved a nation from chaos. They weren’t flawless—pride and power could twist them—but they stood for us, rooted in our soil, not pawns of distant crowns. Now? We’ve got thieves—gutless hustlers who’d sell their own mothers for a handshake with the West. These aren’t leaders; they’re brokers, middlemen in a colonial rerun, pocketing crumbs while our wealth bleeds out. Independence swapped flags but not masters—Africa’s a conquered territory, its governments loyal to the conquerors who drew the lines we’re still trapped in.

Take Nigeria. Its government wasn’t born to serve us—it was birthed to shield British profits, a midwife to exploitation that never cut the umbilical cord. The Land Use Act of 1978, decreed under military rule, nailed the coffin shut on our autonomy. It declares all land in each state vested in the governor, held “in trust” for the people—but don’t be fooled by the noble phrasing. You don’t own land in Nigeria; you lease it, a 99-year squatters’ pass that can be yanked whenever a governor’s whims or a foreign bidder’s wallet demands it. Every inch of soil, every mineral beneath it—oil, tin, gold—belongs to the state, which means it belongs to the suits who cut deals in London or Beijing. The Act’s roots stretch back to colonial land grabs, formalized in 1978 to keep power centralized, not communal. Farmers tilling ancestral plots, miners scraping for survival—they’re tenants on their own heritage, paying rents and taxes to a system that sees them as pawns, not proprietors. By extension, the government owns not just the land but the resources it cradles, doling them out to Shell or Chevron while Lagos slums swell with the displaced.

Congo’s no different—just a gorier verse in the same song. Kids as young as six dig cobalt with bleeding hands, cobalt that powers your phone, your Tesla, your “green” future. Their leaders pocket the change—pennies against the billions raked in by multinationals—while militias and ministers play tag with the profits. The 2002 Mining Code, updated in 2018, mirrors Nigeria’s playbook: all mineral wealth is the state’s, granted to companies through leases that leave locals with dust and graves. Artisanal miners—150,000 to 200,000 strong—scratch out a living, but the real haul goes to China or Canada, not Kolwezi. The state’s “ownership” is a front for extraction, a legal fiction that keeps the Congo a quarry, not a country.

It’s a pattern stitched across Africa. South Africa’s 1913 Natives Land Act, a colonial relic, reserved 87% of the land for whites, leaving blacks with scraps—repealed in 1991, but its ghost lingers in today’s unequal sprawl. Modern laws like the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act of 2002 handed mineral rights to the state, “for the nation,” yet mining giants like Anglo American thrive while townships choke on tailings. In Ghana, the 1992 Constitution vests all mineral resources in the president on behalf of the people, but gold flows to foreign vaults while galamsey miners poison rivers for scraps. Kenya’s 2016 Community Land Act promises communal tenure, but the state can still grab land “for public interest”—code for pipelines or plantations. From Nigeria to the DRC, these laws aren’t protection—they’re plunder dressed up as policy.

Back in the day, our warrior kings led with shields, not briefcases. They fought for us—sometimes to a fault—but their thrones weren’t built on betrayal. Nigeria’s government, a colonial hand-me-down, still kneels to foreign interests, its Land Use Act a leash tying us to 1884’s Berlin Conference. The oil deltas flood with crude, not cash; the mines spit out coltan, not schools. In Congo, kids die for cobalt while their “elected” thieves sip champagne in Kinshasa, propped up by the same West that cries about “sustainability.” The Scramble for Africa never ended—it just got a new logo. Our governments aren’t ours—they’re outposts, loyal to the conquerors, not the conquered. Independence? A flag-waving lie, when the land, the wealth, the future still answer to someone else’s king.

VII. We Are Not Africans: Reclaiming What’s Lost

“African” isn’t a badge—it’s a shackle, a cold iron cuff we didn’t hammer into shape. It’s a name for a simulation, a flickering hologram projected over us by hands that never knew our fire, our roots, our pulse. It’s not who we are—it’s who they need us to be, a blank slate for their script, a prop in their play. But dig past it, peel back the layers of their Berlin-born fiction, and you’ll find what they buried: uprisings that shook their forts, thinkers who outwitted their pens, systems that hummed with a genius they couldn’t fathom. We’re not Africans—not in their shallow, stitched-together sense. We’re something older than their maps, fiercer than their guns, something coiled and waiting to rise. The path out isn’t theirs to give—it’s ours to take, by reclaiming our tongues, our rule, our story.

Some think the way forward is a plane ticket to Europe, an escape hatch from the simulation’s glitches—poverty, corruption, the governments of thieves who sell us out daily. They pack bags, chase visas, and dream of London’s gray streets or Paris’s glittering lights, believing the West’s gleam is salvation. But it’s a mirage, a leap from the frying pan into the fire. The lot of the “African” in Europe—or America, or anywhere their ships once docked—isn’t a golden ticket; it’s a slow burn. You’re a guest until you’re a threat, a worker until you’re a statistic, a face on the news when the riots start. Racism isn’t a rumor there—it’s a rule, etched into wages, housing, the cold stares on the Tube. In 2023 alone, over 40,000 crossed the Mediterranean, fleeing the mess colonialism left—only to drown, get detained, or scrape by in camps. Long run? You’re still tethered to their system, still a cog in their machine, just with better Wi-Fi. It’s not freedom—it’s a prettier cage.

The real way out isn’t running—it’s returning. Rejoin the ancient societies they shattered: the Oyo Empire’s guilds, the Kongo’s councils, the Ashanti’s courts—systems that held us together before their boots hit our shores. Learn the truth about our ancestors—not the cartoon savages of their textbooks, but the architects of Great Zimbabwe, whose stone walls mocked their “discovery“, or the astronomers of Dogon, mapping Sirius before telescopes. These weren’t myths—they were us, sharp and unbowed. Our religious systems? They’re not the “heathen” trash the missionaries smeared them as. Ifa’s divination cracked life’s codes; Vodun bound communities tighter than any cathedral; the Zulu’s inkosi yezulu spoke sky to earth. Where they need refinement—say, shedding old cruelties or adapting to now—refine them, not reject them. We don’t need Rome’s cross or Mecca’s crescent imposed—we’ve got our own stars to steer by.

Travel within our regions, not across their oceans. From Accra to Addis, Nairobi to Niamey, there’s more to share than divide—trade yam for millet, tech for textiles, stories for songs. The Hausa once crisscrossed the Sahel, linking empires without a passport; the Swahili sailed from Mogadishu to Kilwa, stitching coasts into kin. Why beg for crumbs in Frankfurt when we can build tables in Bamako? Together, we’ve got the numbers—1.4 billion strong—the brains, the hands, the will. The languages they tried to kill can roar again—Igbo proverbs in boardrooms, Amharic in classrooms, Wolof on airwaves. Our rule? Not their puppets, but councils and chiefs answerable to us, not Shell or Beijing.

Digging past “African” isn’t nostalgia—it’s rebellion. It’s unearthing Mansa Musa, whose gold crashed Cairo’s markets, or Queen Nzinga, who outfoxed Portugal for decades. It’s reviving Timbuktu’s libraries, not as ruins but as living hubs. We’re not their simulation’s extras—we’re the heirs of something they couldn’t crush, something waiting to rise. Step one: stop running to their shores. Step two: start rebuilding ours. That’s not a dream—it’s a debt to the bones beneath us, and it’s time to pay up.

VIII. Conclusion: Beyond the Simulation

Africa, as we know it, is a fiction—a colonial script scribbled in the smoky rooms of 1884 Berlin, a stage set where we’ve been cast as bit players in someone else’s drama. It’s a name, a border, a story that’s never been ours, a commodity carved up and sold while we were handed the bill. But we’re not Africans—not in their shallow, shackling sense. We’re not the shadows they painted, not the puppets they propped up after toppling our warrior kings, not the converts they lured with their Trojan horse hymns. We’re the heirs of something fiercer—builders of empires, weavers of tongues they couldn’t silence, dreamers who defied the thieves now ruling us. It’s time to rewrite the code, to smash the simulation’s screen and step into the light of who we’ve always been.

This isn’t about mourning a lost Eden—it’s about clawing back what’s ours. The label “African” is a chain we didn’t forge, a glitch we don’t have to live with. Question it—every time it’s spoken, every time it’s written, ask: whose word is this? Reject the game—don’t play by rules rigged in Brussels or Washington, don’t chase their visas or bow to their land-grabbing decrees. Build what’s ours—start where we stand, with the ancient societies waiting to rise, with the scripts and songs they buried, with the unity they fear. We’re not their footnote—we’re the story they couldn’t finish, the fire they couldn’t douse.

The simulation’s cracking. Every child who learns Nsibidi instead of Latin, every council that shuns their bribes, every step we take toward each other—not their shores—widens the fracture. We’re the descendants of Mansa Musa’s wealth, Nzinga’s cunning, Sundiata’s steel. Not Africans in their cage, but something older, deeper, unbound. It’s time to shed the costume, burn the script, and claim the stage. Beyond their simulation lies our truth—let’s go get it.