Every Traditional African Mask You Should Know!

Africa, a continent of unparalleled cultural richness and diversity, has gifted the world with an extraordinary legacy of artistic expression. Among its most iconic and profound creations are traditional African masks—sacred objects that transcend mere aesthetics to embody spirituality, history, and identity. For centuries, these masks have played pivotal roles in rituals, ceremonies, and storytelling, serving as conduits between the physical and spiritual realms. From the intricate wooden carvings of West Africa to the vibrant, symbolic designs of Southern Africa, each mask tells a unique story of the people who crafted it, the tribe it represents, and the region it hails from.

In this ambitious compendium, Every African Mask You Should Know, we embark on a journey across the continent to explore the vast and mesmerizing world of traditional African masks. Organized by region—West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, Southern Africa, and North Africa—this article delves into the distinct mask-making traditions of each area. Within these regions, we examine the contributions of various tribes, offering detailed analyses of their most significant masks. From the towering Gelede masks of the Yoruba in Nigeria to the striking Pende masks of the Congo, we aim to catalog and celebrate as many documented masks as possible, focusing on their cultural context, craftsmanship, and symbolism.

The task of documenting every African mask ever made is, admittedly, a near-impossible feat. Countless masks have been lost to time, remain hidden in private collections, or exist solely within the oral traditions of their communities. Yet, this article dares to make a bold attempt. By drawing on historical records, anthropological studies, and the wisdom of contemporary African artisans, we strive to create the most comprehensive resource on traditional African masks to date. This is not merely a catalog—it is a tribute to the ingenuity and spirituality of African peoples, a definitive guide for enthusiasts, scholars, and curious minds alike.

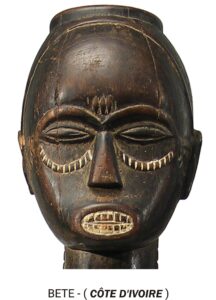

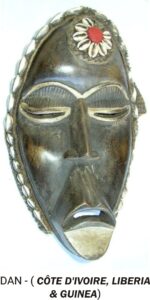

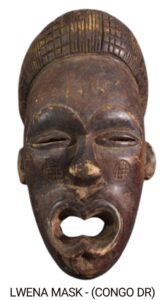

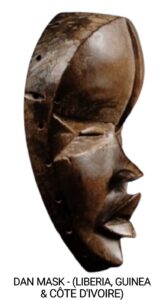

As we traverse the continent region by region, tribe by tribe, and mask by mask, prepare to uncover the profound meanings behind these timeless artifacts. Whether you’re captivated by the haunting beauty of a Dan mask from Liberia or the bold geometry of a Senufo Kpelie mask from Côte d’Ivoire, this compendium promises to illuminate the extraordinary diversity and depth of Africa’s masked traditions. Let us begin this exploration with reverence and curiosity, honoring the legacy of every African mask we can bring to light.

See Our Gallery

1. West Africa: The Heart of Mask-Making Traditions

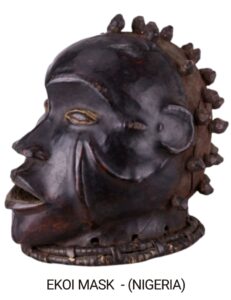

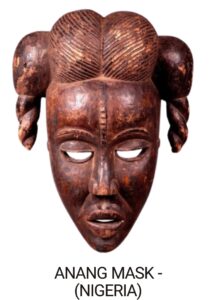

West Africa stands as a cornerstone of traditional African mask craftsmanship, renowned for its intricate wooden carvings that have captivated scholars, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide. This region, encompassing countries such as Nigeria, Mali, Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Ghana, boasts a vibrant legacy of mask-making deeply intertwined with cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and social structures.

Masks here are far more than decorative objects; they are sacred tools wielded in rituals, ceremonies, and performances, often under the auspices of secret societies. These societies—exclusive groups like the Poro and Sande—govern initiation rites, enforce moral codes, and mediate between the living and the ancestral or spiritual realms. Wood carving, the dominant medium, is elevated to an art form through the skilled hands of artisans who infuse each mask with symbolic meaning, reflecting the cosmology, history, and identity of their people.

The prominence of West African masks stems from their multifaceted roles in society. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, masks in this region are “worn during masquerades to represent spirits, ancestors, or deities,” serving as physical manifestations of the unseen world. The use of wood, often sourced from sacred trees like iroko or mahogany, underscores the masks’ spiritual potency, as these materials are believed to house divine energy. Carvers employ techniques passed down through generations, combining chisels, adzes, and natural pigments to create designs ranging from minimalist elegance to elaborate, multi-figure compositions. For instance, the Yoruba Gelede masks, with their towering superstructures, exemplify the region’s flair for dramatic artistry, while the Dan masks of Liberia showcase refined, understated beauty.

Secret societies play a pivotal role in West African mask traditions, particularly in regulating their creation and use. In the Poro society of the Senufo and related groups, masks like the Kpelie are reserved for initiation ceremonies, where they symbolize the transition from youth to adulthood and impart ancestral wisdom. These societies maintain strict protocols, ensuring that only initiated members can craft, wear, or even view certain masks, preserving their mystique and authority. The masks often appear in masquerades—dynamic performances blending dance, music, and storytelling—that reinforce community values and connect the living with the supernatural. Anthropologist John Mack notes in The Art of Small Things that “the mask in West Africa is a vehicle for transformation, embodying the spirit it represents only when activated through performance”.

Rituals, too, are central to West African mask culture, with masks serving as conduits for fertility, protection, justice, and harvest blessings. The Bamana Chi Wara antelope masks, for example, are danced in agricultural rites to honor the mythical being who taught humans to farm, as documented by the National Museum of African Art. Similarly, the Igbo Mgbedike masks, with their fierce, exaggerated features, emerge during warrior ceremonies to invoke strength and intimidate foes. These rituals highlight the masks’ dual nature: they are both artistic masterpieces and functional objects imbued with power, bridging the earthly and the divine.

West Africa’s mask-making tradition is a testament to the region’s artistic ingenuity and cultural depth. The interplay of wood carving, secret societies, and rituals has produced some of the continent’s most iconic masks, each a repository of history and meaning. As we explore the tribes and their specific creations—such as the Yoruba, Dan, Senufo, Bamana, and Igbo—we uncover a rich tapestry of craftsmanship that continues to inspire and inform our understanding of African heritage.

Tribes and Masks:

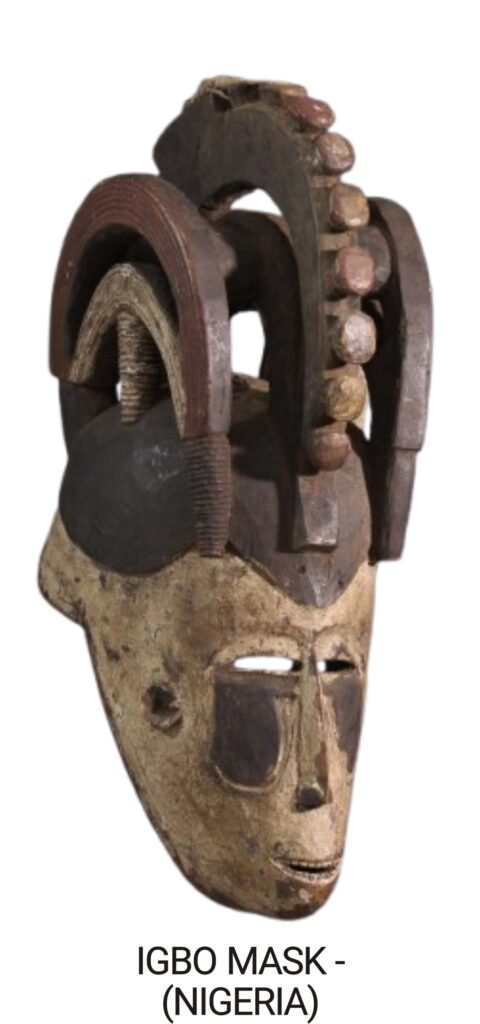

Igbo (Nigeria)

The Igbo people, one of Nigeria’s largest ethnic groups, reside predominantly in the forested regions of southeastern Nigeria, straddling both banks of the Niger River. With a population numbering approximately ten million, the Igbo are a vibrant and industrious community, primarily engaged in farming and trade, supplemented by hunting and fishing. Their society is decentralized, comprising thirty-three subgroups spread across roughly two hundred villages nestled within thick forests and semifertile marshlands. Unlike their neighbors to the north and west—where influences from the Igala and Benin kingdoms introduced hereditary rulers—the Igbo traditionally lack centralized governance. Instead, power resides with family heads who form councils of elders, working in tandem with numerous secret societies that wield significant political and social influence. This unique structure has fostered a remarkable diversity in Igbo culture, particularly in the realm of art and traditional African masks.

The Igbo’s social system emphasizes individual achievement and generosity, with men ascending through hierarchical ranks within secret societies by demonstrating their prowess and community contributions. This lack of overarching centralization has nurtured a kaleidoscope of artistic expressions, notably in sculpture and mask-making. Archaeological evidence from Igbo-Ukwu, a village in Igboland, reveals the antiquity of their artistic tradition. Dating to the 9th century AD, excavations uncovered a distinguished man’s grave and ritual store containing chased copper objects and intricate leaded-bronze castings, marking some of the earliest known sculptures in sub-Saharan Africa. These findings underscore the Igbo’s longstanding mastery of form and material, a legacy that flourishes in their African masks and sculptural works.

Igbo sculpture adheres to strict conventions: figures are typically frontal, symmetrical, and upright, with legs slightly apart, arms extended from the body, and hands open, palms facing outward. While proportions mirror the human body, the neck is often elongated, lending a sense of balance and stability, though lacking the polish of refinement seen in other traditions. Among the most significant sculptural forms are the ikenga statues, carved from hardwood and featuring a pair of ram horns—a symbol of aggression, perseverance, and self-control, as the ram “fights with his head” yet rarely engages in conflict. These statues, scarified to reflect their owner’s status, are acquired by young men at various life stages, with every man owning one by the time he marries and settles. Larger ikenga serve entire communities, lineages, or age groups, distinguished by elaborate horn-themed hairstyles, and are showcased during ceremonies to reinforce collective solidarity.

Equally prominent are the alusi figures, protective deities tied to natural elements like rivers and earth, or social constructs such as markets and ancestors. Housed in familial-style sanctuaries, these statues bear status symbols—intricate hairstyles, scarification, and ornaments—mirroring influential Igbo individuals. A recurring motif is the open palms facing each other, symbolizing frankness, reciprocity, and the symbiotic relationship between humanity and the divine. This artistic tradition sets the stage for the Igbo’s extraordinary mask-making practices, which are integral to their cultural and spiritual life.

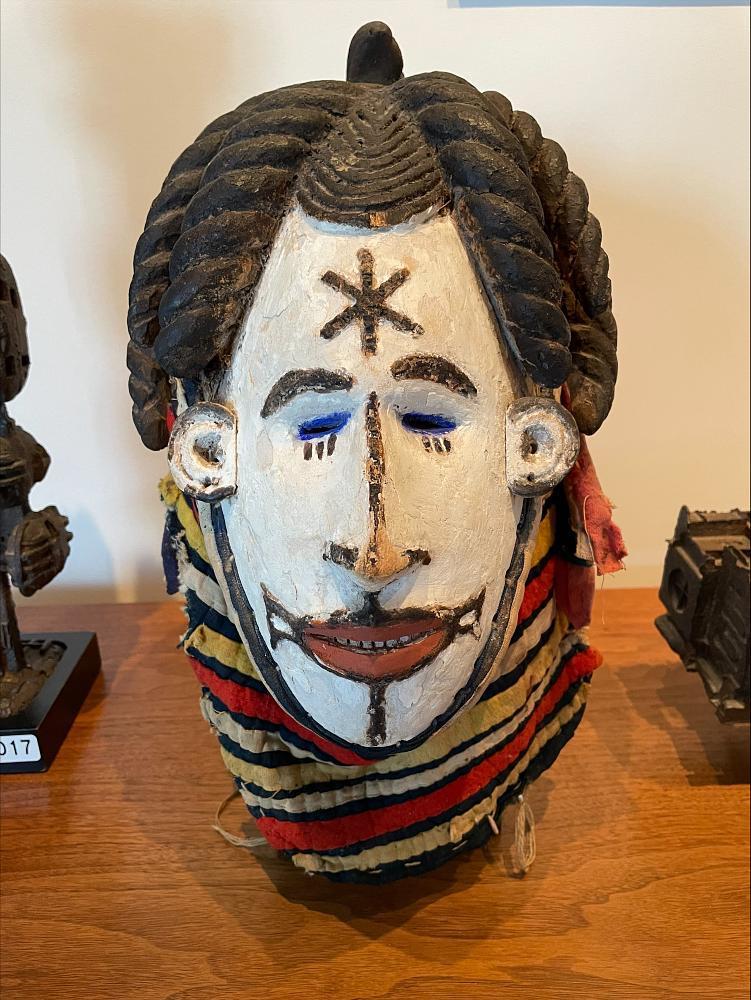

The Igbo employ thousands of traditional African masks, each embodying unspecified spirits of the dead and forming a vast community of souls. A defining feature of many Igbo masks is their chalk-white paint, a color symbolizing the spirit world. Crafted from wood or fabric, these masks are adorned with elaborate costumes—sometimes featuring mirrors—and often cover the dancer’s hands and feet, enhancing their otherworldly presence. In Igbo masquerades, masks juxtapose beauty and bestiality, femininity and masculinity, black and white, reflecting the dualities within their worldview. These performances span a range of dramas, including social satires, sacred rituals honoring ancestors and invoking gods, initiation rites, second burials, and public festivals, some of which now incorporate modern celebrations like Christmas and Independence Day. While certain masks are exclusive to specific festivals, most appear across multiple events, showcasing their versatility.

Among the most celebrated Igbo masks are those of the Northern Igbo mmo society, which represent the spirits of deceased maidens and their mothers. Known as Maiden Spirit masks, these delicate, white-painted creations epitomize beauty and grace, contrasting with masks symbolizing darker forces. In Southern Igboland, the ekpe society—adopted from the Cross River region—employs contrasting masks: the maiden spirit, embodying peace and elegance, and the elephant spirit, symbolizing aggression and ugliness. Similarly, the okorosia masks parallel the mmo, blending tradition with satire. Eastern Igbo masquerades, tied to the harvest festival, feature masks with forms dictated by custom, though their performances adapt annually, incorporating stock characters like Mbeke (the European), Mkpi (the he-goat), and Mba (boy-girl pairs satirizing gender roles).

Beyond masks, Igbo artisans craft an array of decorative objects—musical instruments, doors, stools, mirror frames, kola nut trays, dolls, and divination figures—demonstrating their versatility. Yet, it is their African masks that most vividly encapsulate Igbo culture, blending artistry with spirituality. Performed by masked dancers in elaborate regalia, these masquerades reinforce social norms, celebrate heritage, and connect the Igbo to their ancestors. The decentralized nature of Igbo society has allowed this rich diversity to thrive, making their traditional African masks a cornerstone of both their identity and the broader narrative of African art.

This long-form description highlights the Igbo’s cultural complexity and their profound contribution to the world of traditional African masks, positioning them as a vital thread in the tapestry of West African artistry. Their masks and sculptures, rooted in ritual and community, continue to captivate and educate, preserving a legacy that resonates far beyond the forests of southeastern Nigeria.

Mgbedike Masks: Fierce, exaggerated features for warrior ceremonies.

In the vibrant tapestry of Igbo culture, few figures loom as large as the Mgbedike Masquerade. Known as the “Time of the Brave,” Mgbedike is more than a masked performer—it is a living embodiment of strength, wilderness, and communal identity. Rooted in the traditions of northern Igboland, particularly the Nri-Ọka region, this masquerade commands attention with its towering physique, intricate construction, and profound spiritual significance. To encounter Mgbedike is to witness a bridge between the physical and ancestral realms, a spectacle that has captivated Igbo communities for generations.

A Fearsome Physique and Masterful Build

The Mgbedike mask is a marvel of artistry and intimidation. Standing as a centerpiece of the masquerade, the mask itself is often carved from wood, its surface sculpted with exaggerated features that evoke both reverence and fear. Prominent horns curve skyward, symbolizing power and connection to the divine, while menacing teeth—sometimes jagged or bared in a snarl—project an aura of aggression. The headdress, a defining element, is elaborately adorned with interlocking figures: snakes, monkeys, antelopes, and human forms, each meticulously crafted to reflect the wild essence of the spirit it represents. Examples from the early 20th century, such as those preserved at the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, showcase masks reaching heights of up to 33 inches, a testament to their imposing scale.

The build of Mgbedike extends beyond the mask to the costume, a dynamic assembly of natural and crafted materials. Quills, grasses, and seedpod rattles drape the performer, rustling with every movement to amplify the masquerade’s untamed presence. Basketry, metal, gum, and cloth are woven together with precision, creating a structure that is both durable and flexible—essential for the vigorous dances and competitive displays that define its performances. In some iterations, the costume incorporates vibrant Akwete cloth, beads, and animal skins, adding bursts of color and texture that catch the eye during festivals. This combination of materials and craftsmanship ensures that Mgbedike is not just seen but felt, its physicality resonating through sound and motion.

Cultural Significance: A Spirit of Wilderness and Community

To the Igbo people, masquerades like Mgbedike are far more than artistic expressions—they are sacred conduits to the ancestral world. Mgbedike, in particular, represents a wilderness spirit, embodying qualities of aggression, stubbornness, and unyielding bravery. Its name, translating to “Time of the Brave,” reflects its role as a figure that emerges in moments of challenge or celebration, galvanizing communities through its sheer presence. As cultural historian Chika Okeke-Agulu notes, such masquerades serve as “visual and performative metaphors” for Igbo values, linking the living with their forebears.

Historically, Mgbedike performances have been tied to social order and communal rites. In precolonial Igbo society, masquerades enforced norms, settled disputes, and marked significant events like harvests or initiations. Mgbedike’s fearsome demeanor—often seen chasing onlookers or engaging in mock battles with rival troupes—underscored its authority, believed to be bolstered by supernatural forces. These displays, accompanied by the pulsating rhythms of drums, gongs, and sambas, transformed villages into arenas of spiritual and physical contest. According to Vanguard News, such events remain a “rallying point” for Igbo identity, preserving traditions amid modern change.

The competitive aspect of Mgbedike performances highlights its significance further. Rival masquerade groups vie to outdo one another in endurance, agility, and the potency of their protective charms, a practice that echoes the Igbo emphasis on resilience and excellence. Elders and spectators judge these contests, reinforcing communal bonds and honoring the ancestors believed to animate the masquerade. As documented by the Art Institute of Chicago, Mgbedike’s elaborate design and aggressive persona make it a standout in these rituals, its every leap and roar a tribute to the untamed spirits of the forest and the strength of the people.

Maiden Spirit Masks: Delicate, white-painted masks symbolising beauty.

Among the Igbo people of Nigeria, the Maiden Spirit Masks, known as Agbogho Mmuo or Agbogho Mmwo, stand as delicate masterpieces of art and culture. These white-painted masks, worn exclusively by male dancers, are celebrated for their embodiment of youthful feminine beauty—an ideal that transcends mere physicality to encompass moral purity, grace, and spiritual resonance. With their slender features, elaborate hairstyles, and ethereal white surfaces, these masks serve as a bridge between the living and the ancestral world, captivating audiences during festivals and funerals alike.

A Delicate Physique and Symbolic Build

The Maiden Spirit Mask is a study in refinement. Carved from lightweight wood, its design is intentionally delicate, featuring small, balanced facial features: a narrow, straight nose, petite mouth, and slit eyes that convey serenity. The mask’s surface is coated with white chalk or kaolin clay, a finish that mimics the smooth, glistening skin Igbo culture likens to “beautiful water droplets,” as noted by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. This whitened appearance is not merely aesthetic—it symbolizes ritual purity and the spiritual beauty of the ancestors, aligning the mask with the ethereal realm it represents.

The build of the mask is further enhanced by its elaborate superstructure. Towering coiffures, often crested or adorned with spirals, combs, and openwork discs, rise above the face, showcasing the carver’s virtuosity. These hairstyles, painted in contrasting hues like black or red, reflect historical Igbo fashion and signify wealth and high social standing, as described by the Yale University Art Gallery. The mask is paired with a colorful, tight-fitting costume—often made of appliquéd cloth, beads, and fibers—that accentuates the dancer’s movements, completing the illusion of a lithe, graceful maiden. Together, the delicate mask and vibrant attire create a striking visual harmony, embodying the Igbo ideal of feminine poise.

Cultural Significance: Beauty as a Spiritual Force

The Maiden Spirit Mask’s white-painted delicacy is deeply symbolic. In Igbo cosmology, white is the color of the spirit world, associated with purity, death, and the ancestors. As the Brooklyn Museum explains, these masks glorify youthful female beauty while connecting it to ancestral power, danced by young men to honor deceased maidens and invoke their blessings. The Agbogho Mmuo performance, often part of the annual “Fame of the Maidens” festival or funerals of prominent villagers, is both entertainment and ritual. The dancers’ exaggerated, virtuosic movements parody women’s grace, delighting crowds while reinforcing communal ties to the past.

Beyond aesthetics, the mask represents an idealized femininity that blends physical and moral virtues. The small features and light complexion—highlighted by black tattoos or uli designs on the forehead and cheeks—mirror qualities like obedience, good character, and generosity. The white surface, evoking spiritual cleanliness, suggests these maidens are not just beautiful but morally exemplary, serving as role models for the living. In agricultural festivals, they are believed to promote fertility and prosperity, while at funerals, they escort the departed into the spirit world alongside other masquerades, ensuring safe passage.

The masks’ delicate construction belies their robust cultural role. Worn by men in their late teens or early twenties—contrasting with the older men who perform more aggressive male masks like Mgbedike—they embody a playful yet profound duality. As Herbert M. Cole notes in Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos (Google Books), this interplay of gender and beauty underscores the Igbo concept of masquerades as expressions of duality: beauty and ugliness, male and female, living and dead. The Agbogho Mmuo thus becomes a celebration of life’s contrasts, its white facade a canvas for both joy and reverence.

A Legacy of Elegance in Modern Times

Today, Maiden Spirit Masks remain potent symbols of Igbo heritage. Their delicate, white-painted forms have earned them a place in global collections, from the Nigerian National Museum in Lagos to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. While some were crafted for traditional use—dated to the 19th and early 20th centuries—others, may have been made for export, reflecting their appeal beyond Nigeria. Yet their significance endures in Igboland, where performances continue to mark seasonal and life-cycle events, preserving ancestral connections in a modernizing world.

To behold a Maiden Spirit Mask is to witness a delicate paradox: a fragile object imbued with enduring strength, a white-painted surface radiating timeless beauty. It encapsulates the Igbo reverence for youth, femininity, and the spiritual, offering a glimpse into a culture where art and ancestry intertwine. As both a symbol of idealized beauty and a vessel for communal memory, the Agbogho Mmuo remains a testament to the elegance and depth of Igbo tradition.

Yoruba (Nigeria)

In the heart of western Nigeria, the Yoruba people hold a profound belief that their land is “the navel of the world,” the sacred epicenter where creation itself unfolded and the tradition of kingship was born. According to Yoruba cosmology, it was here that the deities Oduduwa and Obatala descended from the heavens to shape the earth and its inhabitants. Oduduwa, revered as the progenitor of the Yoruba, became the first oni (king) of Ile-Ife, the spiritual and cultural capital of the tribe. To this day, Yoruba kings trace their lineage back to this divine ancestor, cementing Ile-Ife’s status as a hallowed ground. Among the myriad centers of African art, none rivals the ancient town of Ife for its extraordinary achievements across diverse artistic domains, particularly in the realm of traditional African masks and sculpture. This rich legacy, known as Ife art, underscores the Yoruba’s indelible contribution to the cultural tapestry of West Africa.

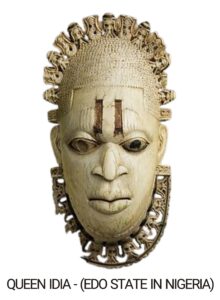

Ife art, named after its place of origin, encompasses an astonishing array of forms: terra-cotta and bronze heads and busts, stone sculptures, quartz-carved stools, religious artifacts, monumental granite monoliths, and statues depicting both humans and animals. Dating from the 12th to the 15th centuries, the terra-cotta and bronze pieces are particularly renowned, with some scholars interpreting them as idealized portraits of onis or dignitaries. These works, cast using the lost-wax method, are near life-size and exhibit meticulous detail—many bronze heads feature faces adorned with fine, parallel lines, possibly representing ritual scarification or body markings unique to Yoruba culture. Around the mouth, lower jaw, and crown of the head, irregularly spaced holes suggest these sculptures were once embellished with necklace-like ornaments or attachments to denote hair, beards, or mustaches. The Ife style shares aesthetic kinship with the later Benin bronzes of the 16th century, hinting at a broader regional influence that reverberates through time.

The Yoruba’s artistic prowess extends beyond static sculpture to the dynamic world of African masks, where their creativity finds expression in rituals and masquerades. While the creators of ancient Ife art have long vanished, their successors—modern Yoruba artisans—continue to draw inspiration from these masterpieces, unearthed through archaeological excavations. Ile-Ife remains a living testament to the tribe’s enduring artistic spirit, a place where the past informs the present. The Yoruba’s mask-making tradition, deeply rooted in their spiritual and social practices, complements their sculptural heritage, with iconic examples like the Gelede and Egungun masks embodying the tribe’s reverence for ancestors, deities, and community harmony. This introduction sets the stage for exploring these traditional African masks, which, alongside Ife’s sculptural wonders, affirm the Yoruba as a pinnacle of artistic and cultural achievement in Nigeria and beyond.

Gelede Masks: Celebrating Female Ancestors with Color and Craft

Among the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria and Benin, the Gelede mask stands as a vibrant testament to the power and reverence of women—both living and ancestral. These masks, integral to the annual Gelede festival, serve a profound purpose: honoring female ancestors, deities, and elderly women, collectively known as “our mothers” (awon iya wa), while placating their spiritual might to ensure communal harmony. Worn by male dancers, Gelede masks combine striking colors and elaborate headpieces to create a spectacle that educates, entertains, and worships, reflecting the Yoruba belief in the delicate balance of life, as encapsulated in the maxim Eso l’aye (“The world is fragile”).

Purpose: Honoring Female Ancestors

The primary purpose of Gelede masks is to pay homage to the spiritual and social influence of women, particularly female ancestors and the great mother deity Iya Nla. In Yoruba cosmology, women possess ase—a life force that can nurture or destabilize society. The Gelede festival, held between March and May, seeks to channel this power for communal good, celebrating maternity, fertility, and moral order while mitigating any destructive potential, as detailed by Henry John Drewal and Margaret Thompson Drewal in Gelede: Art and Female Power Among the Yoruba. Masks are worn during elaborate performances to soothe and appease these “mothers,” ensuring their blessings for prosperity and peace.

Performed by the Gelede society, these rituals honor the dead and the living alike, with dances that invoke ancestral spirits to guide the community through life’s transitions—births, weddings, and funerals. The Gelede performances also educate onlookers, using satire and proverbs to reinforce Yoruba ideals of behavior. A mask depicting a pregnant belly, for instance, warns against taboo pregnancies, while others lampoon colonial figures or rival tribes, blending reverence with social commentary. This dual role—veneration and instruction—underscores the masks’ purpose in maintaining harmony with female ancestors whose powers rival those of gods.

Vibrant Colors: A Palette of Meaning

The Gelede masks burst with vibrant colors, each hue carrying cultural weight. Crafted from wood and painted with natural pigments—reds, yellows, blues, greens, and blacks—these masks dazzle the eye and convey symbolic messages. Red often signifies vitality and courage, yellow abundance, and white the purity of the spirit world. Black accents, derived from charcoal, highlight features or denote strength, while multicolored patterns reflect the diversity of life under women’s influence.

The costumes amplify this vibrancy, featuring layers of cloth in bold, contrasting shades—reds, greens, and golds—adorned with beads and feathers. These flowing, multi-layered ensembles, whirl during dances, embodying the Yoruba ideal of corpulence as a sign of abundance and dignity. The vivid palette not only captivates audiences but also honors the “mothers” by mirroring their dynamic, life-giving essence, a visual feast that celebrates their centrality to Yoruba society.

Elaborate Headpieces: Artistry Above the Mask

The Gelede mask is more than a face covering—it’s a headdress with elaborate headpieces that elevate its artistry and meaning. Resting atop the dancer’s head, the mask comprises two parts: a serene, idealized feminine face below and a towering superstructure above. The face, often painted white or left natural, exudes calmness and patience—qualities prized in women—while the headpiece explodes with creativity, as noted in Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought by Drewal, Pemberton, and Abiodun. These superstructures depict scenes from everyday life or folklore—birds, snakes, hunters, or even modern hats—crafted in wood and painted in bright hues.

Birds atop the headpiece symbolize the nocturnal powers of women as witches, while snakes represent patience and vigilance. Some masks feature figures wrestling pangolins or carrying objects, reflecting life’s struggles and triumphs. Worn with a veil to conceal the dancer’s face, these headpieces—sometimes reaching dramatic heights—transform the performer into a living tableau, honoring female ancestors by showcasing their influence over both the spiritual and physical worlds.

A Living Tradition

Today, Gelede masks remain a cornerstone of Yoruba culture, preserved in collections like the Nigerian National Museum and performed in vibrant festivals. While some were crafted for export their essence thrives in community-sponsored events, where drummers, dancers, and singers bring the masks to life. The elaborate headpieces and vivid colors continue to captivate, a tribute to female ancestors whose power shapes Yoruba life.

To witness a Gelede mask in motion is to see art and ritual converge—honoring the “mothers” with every swirl of color and carved detail. They embody a legacy of respect, creativity, and balance, ensuring that the voices of female ancestors echo through time in a celebration as vivid as the masks themselves.

Egungun Masks: Ancestral Voices in Layers of Fabric

In the spiritual and artistic traditions of the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria and Benin, the Egungun mask stands as a powerful conduit to the realm of ancestral spirits. Far more than a carved face, Egungun is a full-body masquerade, enveloping the performer in layered fabrics that transform him into a living embodiment of the departed. These masks, central to the Egungun festival, connect communities to their ancestors, offering blessings, guidance, and justice, while their elaborate performances weave reverence with spectacle. Through vibrant textiles and dynamic dance, Egungun honors the past while shaping the present.

Connection to Ancestral Spirits

The Egungun mask’s primary purpose is to bridge the living and the dead, serving as a tangible link to ancestral spirits within Yoruba cosmology. In Yoruba belief, ancestors are not gone but remain active in the community, influencing prosperity, morality, and justice. The Egungun masquerade—worn by members of the secretive Egungun society—allows these spirits to return, speak, and interact with the living, as detailed by Henry John Drewal, John Pemberton, and Rowland O. Abiodun in Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought. Performed during annual festivals, funerals, or crises, Egungun ensures that the ancestors’ wisdom and power endure.

Each Egungun represents a specific lineage or individual spirit, its appearance dictated by the ancestor it embodies. Some, like the Egungun Epa, honor warriors with martial displays, while others, such as the Egungun Alaso, reflect wealth and prestige through fabric opulence. The masker’s voice—altered to sound otherworldly—delivers messages, blessings, or reprimands, reinforcing social order. This connection is sacred; the performer is believed to be possessed, his identity concealed to emphasize the spirit’s presence, a practice rooted in Yoruba reverence for the afterlife.

Layered Fabrics: A Tapestry of Identity

Unlike many masks defined by carved wood, Egungun is a costume mask, its power residing in its layered fabrics rather than a facial structure alone. The headpiece, often carved from wood and painted in vibrant hues—reds, blues, yellows—features human or animal faces, but it’s the voluminous textile body that defines the masquerade. Strips of cloth—cotton, velvet, damask, or imported materials like satin—are sewn into long, flowing panels, cascading from the shoulders to the ground.

These layers, often numbering dozens or hundreds, are a kaleidoscope of colors—red for vitality, blue for spirituality, gold for wealth—accented with beads, shells, and mirrors that shimmer as the dancer moves. The fabrics, sometimes patched with aso-oke (handwoven Yoruba cloth), reflect the ancestor’s status, with richer materials signaling higher prestige. The costume’s weight—up to 50 pounds—tests the dancer’s endurance, while its volume creates a swirling, ethereal effect, symbolizing the ancestor’s expansive presence. This textile artistry, as Drewal notes, is a “visual prayer,” honoring the dead with every stitch and hue.

Masquerade Performances: Dance of the Divine

The Egungun masquerade is a performance of awe and interaction, bringing ancestral spirits to life through dance, song, and ritual. Held in public squares or family compounds, these events feature drummers beating bata and dundun rhythms, guiding the masker’s movements—slow and stately for elder spirits, wild and acrobatic for warriors. The dancer spins, causing the layered fabrics to flare outward, a mesmerizing display that evokes the wind of the spirit world. Onlookers cheer, offer gifts, or shrink back in fear, as some Egungun wield whips or sticks to enforce respect or chase mischief-makers.

Performances vary by type: Egungun Alapansanpa jest with satirical dances, while Egungun Ologede bless with gentle sways, as documented in Egungun: Yoruba Ancestral Masquerade by Marilyn Houlberg. The masker’s anonymity—ensured by a mesh veil over the face—heightens the mystique, allowing the ancestor to speak through blessings, proverbs, or warnings. These events, often spanning days during the dry season, strengthen lineage ties and communal identity, a living dialogue with the past that balances reverence with celebration.

A Legacy Woven in Time

Today, Egungun masks remain vital to Yoruba culture, preserved in collections like the Nigerian National Museum and performed in festivals worldwide, from Oyo to the diaspora. While some costumes were crafted for export, their essence thrives in ritual contexts, where they continue to summon ancestors with every swirl of fabric. The layered textiles and dynamic performances embody a tradition that honors the dead as active participants in life, a testament to Yoruba resilience and reverence.

To encounter an Egungun mask is to feel the pulse of ancestry—a cascade of color and motion that bridges worlds. It stands as a woven monument to the spirits who guide, judge, and bless, their voices carried on the threads of a vibrant legacy.

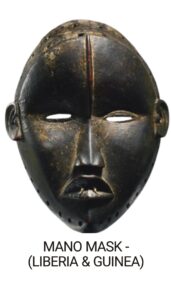

Dan (Liberia/Ivory Coast): Guardians of Spirit and Society

Nestled along the lush, forested borderlands of Liberia and Ivory Coast, the Dan people have cultivated a profound artistic and cultural legacy that resonates deeply within the realm of traditional African masks. Renowned for their exquisite wood-carving techniques and intricate spiritual practices, the Dan—also known as the Gio or Yakuba in some regions—number approximately 350,000 and thrive as farmers, cultivating crops like rice, yams, and cocoa. Their society is organized into small, autonomous villages, each governed by councils of elders and influenced by powerful secret societies, such as the Poro for men and the Sande for women. These societies oversee initiation rites, maintain social order, and serve as conduits to the spiritual world, with African masks playing a central role in their rituals and performances. The Dan’s mask-making tradition, characterized by a remarkable balance of aesthetic refinement and symbolic potency, positions them as one of West Africa’s most celebrated artistic communities.

The Dan believe that masks are not mere objects but vessels for du, spiritual entities that mediate between the human and supernatural realms. Carved primarily from hardwood such as mahogany or iroko, these masks are crafted by skilled artisans who undergo rigorous training, often within secret societies, to ensure their creations embody both beauty and power. The process involves not only technical precision but also ritual consecration, as the mask must be “awakened” through offerings and ceremonies to house its spirit. According to anthropologist Eberhard Fischer, Dan masks are “extensions of the forest’s sacred forces,” reflecting the tribe’s deep connection to their environment. Once activated, these masks are worn by initiated dancers in masquerades—dynamic performances blending music, dance, and storytelling—that reinforce community values, resolve conflicts, and honor the spiritual world.

Deangle Masks: Embodying Peace and Harmony

Among the Dan’s most iconic creations are the Deangle masks, distinguished by their gentle, feminine features and serene expressions. These masks, often characterized by almond-shaped eyes, a smooth forehead, and delicately curved lips, are designed to evoke calmness and compassion. The Deangle—sometimes spelled Deanglé—is typically worn by a male dancer who assumes a female persona, embodying the nurturing and peacekeeping roles vital to Dan society. Adorned with elaborate coiffures, beads, and sometimes cowrie shells, the mask is paired with flowing raffia skirts and soft fabrics, enhancing its graceful presence during performances.

The Deangle mask serves as a mediator in village disputes, appearing at ceremonies to soothe tensions and foster reconciliation. Its role extends to welcoming visitors and blessing community events, such as harvests or initiations, where its tranquil aura promotes unity. A symbol of idealized femininity, reflecting the Dan’s reverence for balance in social interactions”. The mask’s polished surface, often blackened with natural dyes or soot, contrasts with the vibrant colors of its accessories, creating a striking visual harmony. In performance, the Deangle dancer moves with measured elegance, embodying the spirit’s role as a caretaker of communal peace. This mask’s enduring significance lies in its ability to bridge divides, making it a cornerstone of Dan culture and spiritual life.

Tankagle Masks: Enforcers of Justice

In stark contrast to the Deangle, the Tankagle masks embody authority and fierceness, serving as instruments of judicial enforcement within Dan communities. These masks are designed with bold, angular features—prominent brows, wide mouths, and sometimes protruding elements like horns or animalistic motifs—that convey strength and intimidation. Crafted to inspire awe, Tankagle masks often incorporate rougher textures and darker finishes, with minimal ornamentation to emphasize their stern purpose. The name Tankagle (or Tankagli) translates loosely to “judge” or “enforcer,” reflecting their role in upholding social order.

Worn by members of male secret societies, Tankagle masks appear during trials, initiation rites, or moments requiring discipline, such as punishing infractions against community norms. The dancer, cloaked in heavy raffia or animal hides, moves with deliberate force, amplifying the mask’s commanding presence. The Tankagle is believed to channel a powerful du capable of discerning truth and meting out justice, making its appearances both feared and respected. The Tankagle mask’s fierce design underscores its role as a guardian of moral and spiritual law”. Unlike the Deangle, which invites dialogue, the Tankagle demands compliance, ensuring that societal boundaries remain intact.

The Broader Context of Dan Mask Culture

The interplay between masks like the Deangle and Tankagle reflects the Dan’s nuanced understanding of balance—between peace and authority, femininity and masculinity, community and individual. Beyond these, the Dan produce a variety of other masks, each with specific roles: Gle Va masks for war and protection, Bagle masks for entertainment, and Gunye Ge masks for racing competitions among young men. These traditional African masks are rarely static objects; they come alive in masquerades, where the dancer’s movements, accompanied by drums and songs, fully activate the du within. The masks’ diversity mirrors the complexity of Dan society, where every spirit serves a purpose, from healing to celebration to governance.

Dan artisans also craft complementary objects—wooden ladles, musical instruments, and ritual spoons—that share the masks’ aesthetic principles: smooth curves, polished surfaces, and symbolic motifs. Yet, it is their African masks that remain the pinnacle of their artistic expression, revered globally for their craftsmanship and cultural depth.

The Dan people’s mask-making tradition is a testament to their ingenuity and spiritual sophistication, weaving together art, ritual, and social order. Through masks like the Deangle and Tankagle, they navigate the delicate balance of harmony and justice, ensuring their communities thrive in the forests of Liberia and Ivory Coast. This rich heritage of traditional African masks not only defines Dan identity but also enriches the broader narrative of West African artistry, inviting admiration and study from across the globe.

Senufo (Ivory Coast/Mali): Artisans of Ritual and Symbolism

Spanning the savanna and forest regions of northern Ivory Coast, southern Mali, and parts of Burkina Faso, the Senufo people form a vibrant cultural group renowned for their sophisticated artistry and deeply rooted spiritual traditions. Numbering over 1.5 million, the Senufo are primarily agriculturalists, cultivating crops such as millet, sorghum, and yams, while also excelling as skilled artisans in wood carving, metalwork, and weaving. Their society is organized into matrilineal villages, governed by councils of elders and guided by the powerful Poro and Sandogo secret societies, which oversee rites of passage, divination, and community welfare. At the heart of Senufo cultural expression lies their mastery of traditional African masks, which serve as sacred conduits to the spiritual realm, embodying the tribe’s reverence for ancestors, nature, and social harmony. The Senufo’s mask-making tradition, marked by elegant forms and intricate symbolism, establishes them as pivotal contributors to West Africa’s artistic legacy.

For the Senufo, masks are not mere aesthetic objects but manifestations of spiritual forces, crafted with precision by specialized artisans, often members of the Kulebele caste, a subgroup dedicated to carving. These masks, typically hewn from dense woods like iroko or kapok, are shaped using traditional tools—adzes, chisels, and knives—and adorned with natural pigments, cowrie shells, or metal accents. The creation process is steeped in ritual, as artisans consult diviners to ensure the mask aligns with its intended purpose, whether for initiation, harvest celebrations, or funerary rites. The Poro society, central to male education and governance, and the Sandogo society, focused on female divination, frequently commission masks to facilitate their ceremonies. This spiritual potency comes alive in masquerades, where masked dancers, accompanied by rhythmic drumming and song, embody supernatural beings to guide and protect their communities.

Kpelie Masks: Elegance in Initiation

The Kpelie (or Kpeliye’e) mask is among the Senufo’s most iconic creations, revered for its refined oval shape and intricate symbolic motifs. Characterized by a smooth, elongated face with slit eyes, a small mouth, and a high forehead, the Kpelie often features delicate projections—horns, bird figures, or crescent shapes—that evoke animals or ancestral spirits. These animal motifs, such as chameleons or birds, symbolize wisdom, fertility, and protection, reflecting the Senufo’s intimate connection to the natural world. The mask’s surface is typically polished to a glossy finish, sometimes blackened with soot or decorated with kaolin, and may include scarification-like patterns that mirror Senufo body art.

Used primarily in Poro society initiations, Kpelie masks appear during ceremonies marking the transition of young men through various stages of maturity, imparting moral teachings and ancestral knowledge. Worn by initiated dancers, the mask is paired with a costume of raffia and cloth, transforming the wearer into a spirit intermediary. The Kpelie also features at funerals, where it honors the deceased and ensures their safe passage to the ancestral realm. Its delicate, androgynous features—neither distinctly male nor female—embody balance, a core Senufo value, as highlighted by the British Museum’s collections, which describe the mask as “a mediator between human and divine realms”. In performance, the Kpelie dancer’s graceful movements, synchronized with gong rhythms, captivate onlookers, reinforcing community cohesion and spiritual continuity. This mask’s elegance and versatility make it a hallmark of Senufo African masks.

Firespitter Masks: Power in Agricultural Rites

In contrast to the understated Kpelie, the Firespitter mask—known as Kponyungo or “fire-spitter”—is a bold, composite helmet that commands attention with its dramatic design and formidable presence. These large, heavy masks combine zoomorphic elements, blending features of antelopes, warthogs, crocodiles, and other creatures into a fearsome whole. Typically adorned with horns, gaping jaws, and protruding tusks, Firespitter masks are painted in vibrant red, black, and white hues, with some incorporating metal teeth or actual animal hides for added impact. The name derives from myths of the mask’s ability to emit fire or sparks, a symbolic gesture of purification and protection, though in practice, this effect is achieved through ritual or theatrical flair.

The Firespitter is closely tied to agricultural rites, appearing in ceremonies to ensure bountiful harvests and ward off malevolent forces. Worn by Poro society members, the mask is danced in vigorous, acrobatic performances that showcase the wearer’s strength and the spirit’s dominance over chaos. Its role extends to funerals of prominent individuals, where it clears spiritual impurities, and to initiations, where it tests the courage of young men. The Brooklyn Museum notes that the Kponyungo “embodies the Senufo ideal of collective strength, uniting diverse elements into a single, powerful form”. The mask’s composite nature reflects the Senufo’s belief in the interconnectedness of all life, with each animal element contributing a specific attribute—speed, ferocity, or resilience—to the spirit’s arsenal. In masquerades, the Firespitter’s thunderous presence, amplified by drums and chants, galvanizes communities, affirming their resilience against adversity.

The Senufo Mask Tradition in Context

The Kpelie and Firespitter masks represent two poles of Senufo artistry—refinement and raw power—yet they share a common purpose: to mediate between the human and spiritual worlds. The Senufo produce other masks as well, such as Wanyugo masks for divination and Katyi masks for entertainment, each tailored to specific rituals or social functions. These traditional African masks are complemented by an array of carved objects—staffs, doors, figurines, and divining tools—that echo their aesthetic of clean lines and symbolic depth. The Senufo’s decentralized society, coupled with the influence of Poro and Sandogo, has fostered a rich diversity of forms, allowing artisans to adapt masks to local needs while preserving their sacred essence.

Senufo masquerades are communal events, drawing villagers together to witness the embodiment of their beliefs. The Kpelie’s serene dances contrast with the Firespitter’s explosive energy, yet both reinforce the Senufo’s commitment to balance—between tradition and innovation, individual and collective, earth and spirit. This dynamic interplay has earned Senufo African masks a place in global collections, with institutions like the Yale University Art Gallery preserving their legacy for study and admiration.

The Senufo people’s mask-making tradition is a testament to their artistic ingenuity and spiritual depth, weaving together the threads of agriculture, ritual, and community into a vibrant cultural tapestry. Through masks like the Kpelie and Firespitter, they honor their ancestors, celebrate the land, and navigate life’s complexities, leaving an indelible mark on the world of traditional African masks. In the villages of Ivory Coast and Mali, the Senufo continue to carve their story, one mask at a time, ensuring their heritage endures for generations to come.

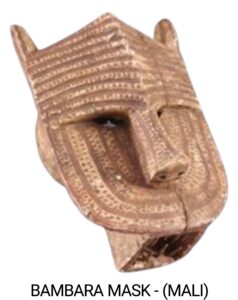

Bamana (Mali): Sculptors of Spirit and Soil

In the sun-scorched savannas and riverine plains of central and southern Mali, the Bamana (also known as Bambara) people have forged a cultural identity that resonates with artistic brilliance and spiritual depth. Numbering approximately 4 million, the Bamana are predominantly farmers, cultivating millet, sorghum, and cotton along the Niger River’s fertile banks, while also practicing animal husbandry and trade. Their society is structured around extended families and villages, guided by councils of elders and six key initiation societies—N’tomo, Komo, Kore, Nya, Kwore, and Chi Wara—which regulate social, moral, and spiritual life. These societies, particularly N’tomo and Chi Wara, are the crucible for the Bamana’s renowned traditional African masks, which embody the tribe’s reverence for fertility, community, and the sacred rhythms of the earth. The Bamana’s mask-making tradition, characterized by bold forms and profound symbolism, establishes them as luminaries in West Africa’s artistic landscape.

For the Bamana, masks are sacred objects that channel spiritual forces, crafted by skilled artisans from the Numu blacksmith caste, who are revered for their mastery of wood and metal. Carved from hardwoods like daba or sangha, these masks are shaped with adzes and knives, then embellished with natural pigments, cowrie shells, beads, or metal studs to enhance their potency. The creation process is a sacred act, often accompanied by rituals to invoke the mask’s intended spirit, ensuring it serves as a bridge between the human and divine. Bamana masks come alive in masquerades—vibrant performances of dance, drumming, and song—that mark initiations, harvests, and communal rites, reinforcing social bonds and honoring ancestral wisdom. The Bamana’s artistic vision, rooted in their agricultural lifestyle and spiritual cosmology, infuses their African masks with a dynamic interplay of form and function.

N’tomo Masks: Guiding Youth to Wisdom

The N’tomo mask, a cornerstone of Bamana initiation practices, is a striking creation designed to shepherd young boys through the early stages of their moral and social education. Distinguished by its abstract, rectangular form and prominent horns—ranging from two to eight, arranged in pairs—the N’tomo mask exudes a sense of authority and mystery. The horns, often interpreted as symbols of growth, fertility, or spiritual power, crown a smooth, featureless face with small, slit eyes and a minimal mouth, emphasizing silence and discipline. Some N’tomo masks are adorned with cowrie shells or red seeds, signifying wealth and protection, while others remain starkly unembellished to underscore their solemn purpose.

Used exclusively within the N’tomo society, the mask appears during ceremonies for boys aged seven to twelve, teaching them values like respect, restraint, and community responsibility. The wearer, typically a senior initiate, dances with measured steps, embodying the mask’s spirit, which enforces silence among the boys—a metaphor for listening and learning. The N’tomo mask’s horned design reflects the Bamana’s belief in the transformative power of initiation, guiding youth from innocence to maturity. In performance, the mask’s stark simplicity contrasts with the lively rhythms of balafon and drums, creating a profound sensory experience that imprints its lessons on both participants and onlookers. This mask’s role in shaping Bamana youth underscores its significance in the tribe’s culture, fostering a foundation of moral integrity.

Chi Wara Antelope Masks: Celebrating the Gift of Agriculture

The Chi Wara (or Tyi Wara) mask, one of the Bamana’s most celebrated creations, is a vertical, sculptural masterpiece that honors the mythical antelope who taught humans the art of farming. These masks, typically carved in pairs to represent male and female antelopes, feature graceful, elongated forms with sweeping horns, zigzag patterns, and stylized bodies that evoke the animal’s agility and elegance. The male Chi Wara is often taller, with vertical horns and a phallic element symbolizing fertility, while the female version cradles a fawn, emphasizing nurturing and abundance. Crafted from wood and adorned with metal, fiber, or beads, the masks are lightweight yet visually commanding, designed to be worn atop the head rather than over the face.

The Chi Wara appears in agricultural festivals, danced by young men who mimic the antelope’s bounding movements to celebrate planting and harvest seasons. Worn with a raffia costume that obscures the dancer’s body, the mask transforms its wearer into the Chi Wara spirit, blessing the fields and inspiring farmers to excel in their labor. The performance, accompanied by call-and-response songs and drumming, is both a spiritual invocation and a communal celebration, honoring the symbiosis between humanity and the land. The Chi Wara’s fluid, abstract design—often compared to modernist sculpture—captures the Bamana’s reverence for nature’s cycles, making it a global icon of traditional African masks.

Analysis: Themes, Materials, and Influences

The N’tomo and Chi Wara masks illuminate core themes in Bamana culture: fertility, initiation, and spirituality. The N’tomo’s horns and the Chi Wara’s antelope form both celebrate fertility—human and agricultural—reflecting the Bamana’s dependence on the land and their desire for prosperity. Initiation, embodied by the N’tomo’s role in guiding youth, underscores the tribe’s commitment to social cohesion, while the Chi Wara’s agricultural focus elevates farming to a spiritual act, linking human effort to divine favor. Spirituality permeates both masks, as they channel unseen forces to bless, teach, and protect the community, reinforcing the Bamana’s animist worldview.

Materials play a critical role in Bamana mask-making. Hardwood provides durability and resonance, allowing masks to withstand vigorous dances while carrying symbolic weight as a product of the earth. Beads, cowrie shells, and metal accents—often sourced through trade—add visual richness and signify wealth or status, while natural pigments like ochre and charcoal deepen the masks’ spiritual aura. The N’tomo’s minimalism contrasts with the Chi Wara’s ornate complexity, yet both showcase the Numu artisans’ skill in balancing form and meaning.

Regionally, the Bamana draw inspiration from neighboring groups like the Dogon and Malinke, sharing motifs like horns and animal imagery that reflect the Sahel’s pastoral heritage. The Chi Wara’s verticality echoes Senufo Firespitter designs, suggesting a broader West African aesthetic dialogue, while the N’tomo’s abstract form aligns with the region’s emphasis on spiritual symbolism over realism. Trade routes along the Niger River facilitated exchanges of materials and ideas, enriching Bamana artistry with Islamic and Mande influences, yet their masks remain distinctly rooted in local traditions.

The Bamana’s African masks extend beyond N’tomo and Chi Wara to include Komo masks for divination and Kore masks for satire, each serving a unique societal function. These creations, paired with carved doors, staffs, and puppets, form a holistic artistic tradition that celebrates life’s milestones. In masquerades, the Bamana transform their villages into theaters of spirit and story, where masks like N’tomo and Chi Wara weave together the threads of fertility, learning, and devotion. Through their artistry, the Bamana of Mali continue to honor their ancestors and their land, leaving a legacy of traditional African masks that captivates the world with its beauty and depth.