Traditional African Masks: Five Iconic Treasures Held in Captivity by European Collections

Traditional African masks are far more than mere objects of beauty—they are sacred vessels of culture, spirituality, and communal identity. Across West, Central, and Southern Africa, these masks have long been integral to ceremonies like harvest celebrations, funerals, and rites of passage, acting as conduits between the physical and spiritual realms. Crafted from materials like wood, ivory, and metal, and often adorned with paint or beads, they embody the histories and values of their creators. Yet, during the colonial era, many of these treasures were forcibly taken by European powers, leaving them “in captivity” in Western museums. This article explores five iconic traditional African masks captured by Europeans, their stories of removal, and the growing activist movement demanding their return.

Table of Contents

Toggle

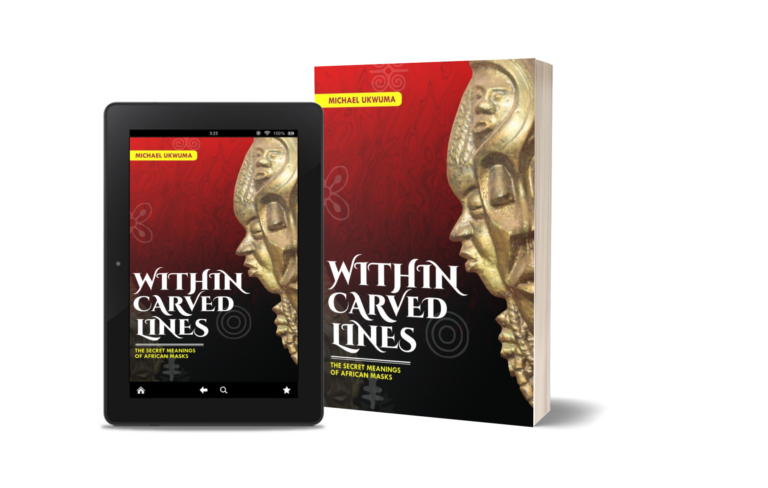

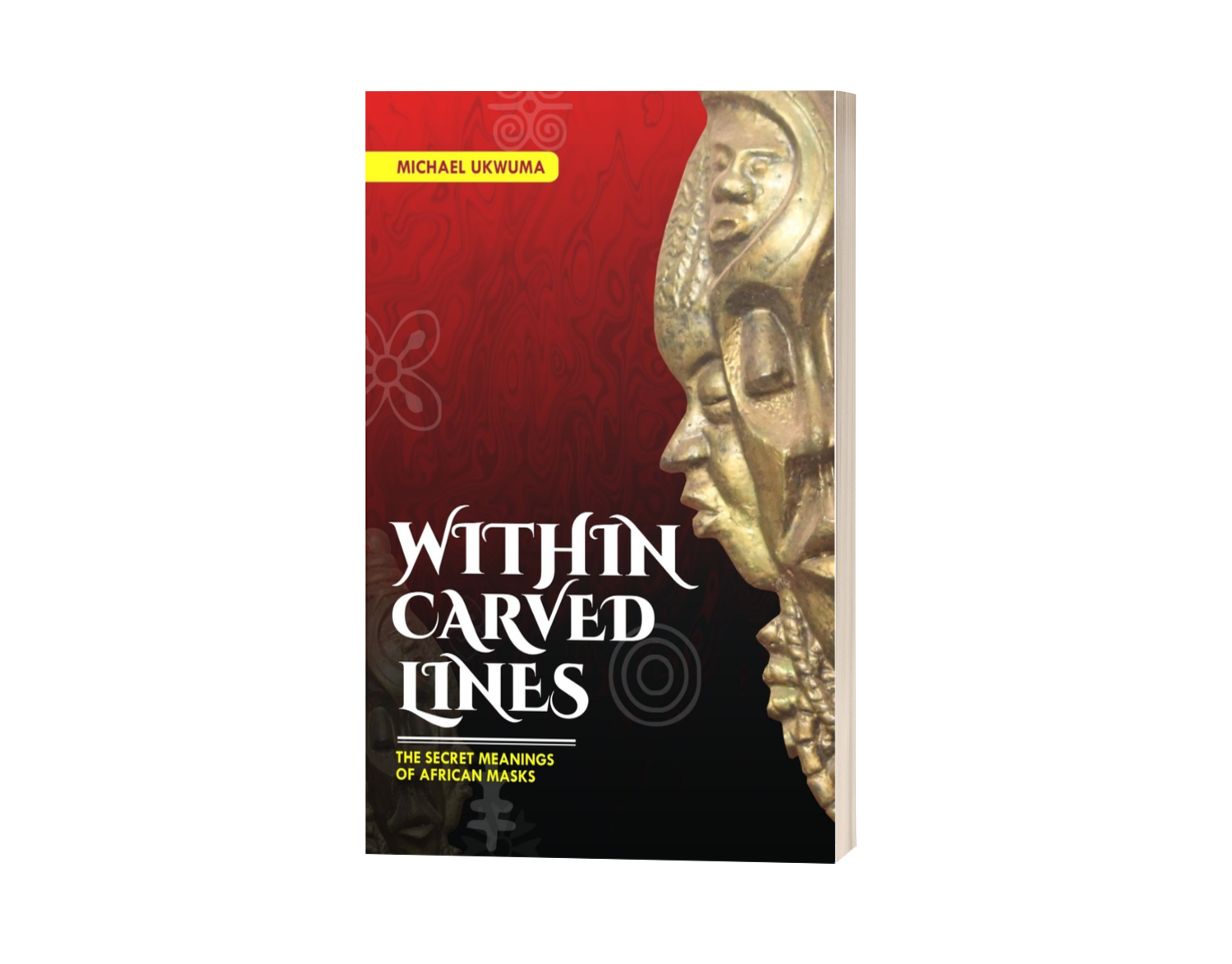

Within Carved Lines: The Secret Meanings of African Masks

The Cultural Significance of Traditional African Masks

Traditional African masks are deeply functional, unlike Western art often made for display. They are worn in rituals to honour ancestors, invoke spirits, or resolve disputes—such as the masquerade performances of the Igbo in Nigeria, which facilitate social justice. Each mask’s design, from abstract shapes to intricate carvings, reflects its community’s beliefs. However, the colonial period saw these sacred items looted, reclassified as “art” by Europeans, and stripped of their context. The masks highlighted here are not just masterpieces but symbols of a broader struggle for cultural restitution.

1. Benin Ivory Mask (Queen Idia Mask): A Royal Symbol of Resilience

The Benin Ivory Mask, linked to Queen Idia of the 16th-century Benin Kingdom (modern-day Nigeria), is among the most renowned traditional African masks. Carved from ivory, it features a calm face with iron-inlaid eyes and scarification marks, topped with a row of heads symbolizing Portuguese traders. Used in royal ceremonies, it represented Edo power and prestige.

Its capture came during the 1897 Benin Expedition, a punitive British raid that sacked Benin City, stealing thousands of artifacts. Today, a prominent example sits in the British Museum, viewable here. Activists like Nigerian historian Enotie Ogbebor argue, “These masks are our heritage, stolen in violence. Their return is a matter of justice, not charity.” The mask’s fame has made it a rallying point for repatriation, spotlighted in articles like ARTnews’s coverage of restitution debates.

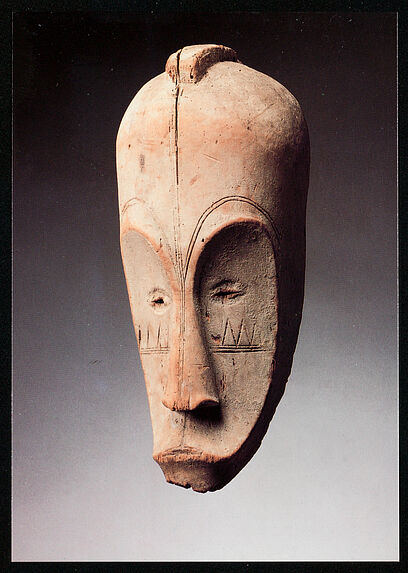

2. Fang Ngil Mask: The Abstract Power of Justice

Originating from the Fang people of Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and Cameroon, the Fang Ngil Mask is a stark, elongated wooden mask, often painted white with black accents. Worn by the Ngil society to enforce justice, its abstract form intimidated wrongdoers and invoked spiritual authority—a hallmark of traditional African masks.

Collected during French colonial rule in the late 19th century, often under duress, it now resides in places like the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris among their prized collections. Congolese activist Emery Mwazulu Diyabanza, who famously removed African artifacts from museums in protest, declares, “These masks are prisoners of war. We will not stop until they are free.” His sentiments echo in Hyperallergic’s report on repatriation activism. The mask’s influence on artists like Picasso underscores its global impact, yet its removal remains a wound.

3. Baule Goli Mask: Harmony in Celebration

The Baule Goli Mask, crafted by the Baule of Ivory Coast, is a circular wooden mask with horns symbolizing the sun and buffalo strength. Used in dances for harvest festivals and funerals, it exemplifies the communal joy embedded in traditional African masks. Its polished finish reflects the Baule’s aesthetic ideals.

Acquired during French colonization—often through trade or force—it’s now in collections like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, viewable here. Ghanaian artist El Anatsui laments, “These masks belong in our villages, not glass cases. They’re alive with our stories.” His views align with OkayAfrica’s exploration of repatriation politics. The mask’s journey reflects the commodification of sacred objects under colonial rule.

4. Sowei Mask (Bundu Mask): A Feminine Legacy

The Sowei Mask, from the Mende of Sierra Leone, is a rare traditional African mask tied to the Sande society, a women’s group overseeing girls’ initiation rites. This black wooden helmet mask, with its high forehead and neck rings, symbolizes feminine beauty and moral strength.

Collected during British colonial rule in the 19th century, often by missionaries dismissive of its sacred role, it’s now in the British Museum, seen here. Activist Sierra Leonean scholar Nemata Blyden asserts, “These masks are our women’s legacy, stolen to decorate foreign halls. Repatriation heals our history.” Her stance is echoed in The Guardian’s coverage of restitution efforts. Its uniqueness amplifies its repatriation urgency.

5. Dan Mask: Elegance in Spirituality

The Dan Mask, from the Dan people of Liberia and Ivory Coast, is a minimalist wooden mask with slit eyes and a high forehead. Used in ceremonies to connect with spirits, it’s a quintessential example of traditional African masks as spiritual tools, embodying elegance and potency.

Taken during French and British colonial expeditions, it’s now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, viewable here. Liberian repatriation advocate Kweku Andrews cries, “Our masks are not trophies—they’re our soul. Europe must return them.” His passion resonates in National Geographic’s repatriation discussion. The mask’s simplicity belies its deep cultural loss.

The Legacy of Traditional African Masks in Western Hands

The Benin Ivory Mask, Fang Ngil Mask, Baule Goli Mask, Sowei Mask, and Dan Mask share a colonial fate—looted during events like the Scramble for Africa (1881–1914), when European powers carved up the continent. Now in Western museums, they’re admired as art, but activists argue they’re hostages of history. Diyabanza’s bold actions and voices like Ogbebor’s fuel a movement detailed in BBC’s repatriation analysis.

For visuals, museum links provide access, but the real call is for return—not just of objects, but of dignity. As debates grow, these traditional African masks remain at the heart of a fight to reclaim Africa’s stolen heritage.